You don’t normally expect to get a CD with an exhibition catalog, as the visual and musical arts tend to exist on separate planes. But for “Erik Satie et son temps” (“Erik Satie and his Times”) at the Bunkamura Museum of Art, it makes perfect sense that a CD of Satie’s music has been included.

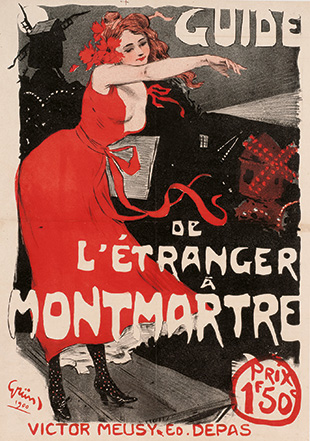

by Jules Grün

(Photo courtesy of Bunkamura Museum of Art)

Normally, one would go to Bunkamura either to see an exhibition of art or to listen to a music concert—it’s also one of our city’s chief concert venues. With this show, visitors end up doing a bit of both, with music constantly piped into the exhibition through localized speakers, to enhance the visual experience.

Erik Satie (1866-1925) was a famous avant-garde composer and pianist, who was at the height of his creativity around the turn of the 20th century. Although he was a successful musician, his music inspired a lot of visual art as well. The Surrealist artist Man Ray aptly said that he was “the only musician with eyes,” referring to the keen visual sense he showed, both in his evocative compositions and his collaborations with visual artists, including Pablo Picasso and André Derain.

The exhibition dwells on a period and a place—Paris—that’s dear to the hearts of Japanese art lovers, and the show works hard to recreate a sense of this world, mainly through large, impressive posters. Some of these show the stars of the day, like Loie Fuller, famous for her manic Serpentine dance (available on YouTube); while others hint at political tensions, like the poster advertising La Lanterne, an anti-clerical journal of the day that opposed Catholic conservatism in favor of the more liberal attitudes represented by the likes of Satie.

Interestingly, this conservative-liberal conflict etched itself in the cityscape of Paris, as the Eiffel Tower was famously built so as to ensure that a modernist icon was the tallest structure in Paris, rather than the Church of the Sacred Heart, which had been recently built on top of Montmartre as a reassertion of Catholic traditionalism.

(Photo courtesy of Bunkamura Museum of Art)

Most of the items at the show are more specific to Satie, however, including his meticulously-written musical scores, with accompanying illustrations by Charles Martin; and artwork for the modernist ballet Parade, which debuted in 1917, during the height of World War I. The backdrops and costumes for this ballet were designed by Picasso in a style that references his Cubism and earlier paintings of circus performers. The show includes some sketches and studies by the Spanish artist, as well as photos and a video of a recent staging, true to the original.

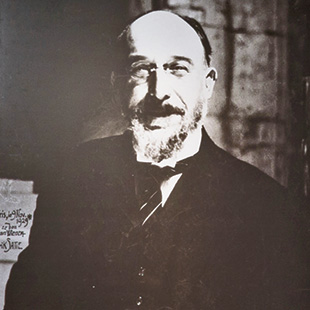

Last but not least, there are plenty of portraits of Satie himself, revealing that the bearded man with a bowler hat and pince-nez was something of an iconic figure. These include doodles by Jean Cocteau; a pointillist portrait by Antoine de La Rochefoucauld, showing Satie aged 28; and Man Ray’s own later tribute, La Poire d’Erik Satie, in which he whimsically reduced the composer to a piece of fruit.

Those who love this period, the man, and his music, will enjoy this show. Otherwise, it might seem a tad twee.

Bunkamura Museum of Art, until Aug 30. www.bunkamura.co.jp/english/museum/