September 27, 2013

Autumn Reading

A look at some new titles to fill out your bookshelf

By Metropolis

Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on September 2013

Although Westerners are used to making a summer reading list to find the perfect paperback to bring to the beach, Japanese associate reading with autumn, when the longer nights give more time to curl up with a good book. As Tokyo cools down, Metropolis looks at some new titles to fill out your bookshelf.

My Awesome Japan Adventure

By Rebecca Otowa

Tuttle, 2013, 48pp, ¥1,800

Writer and long-time Japan resident Rebecca Otowa provides an engaging introduction to the culture, society, food and fun of the country in this children’s book. Rather than take a encyclopedic approach with entries on sushi and ninja, Otowa presents a fictional, generously illustrated travelogue from the perspective of an American fifth grade boy on a four-month homestay. Entertaining and essential reading that presents little ones growing up in Japan with the information they need to survive.

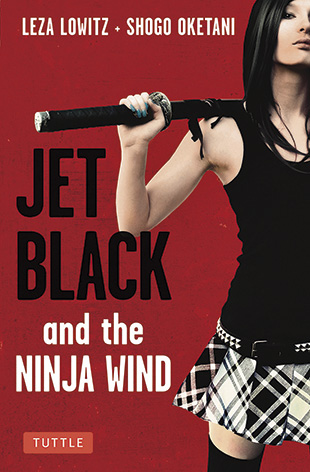

Jet Black and the Ninja Wind

By Leza Lowitz and Shogo Oketani

Tuttle, 2013, 320pp, ¥1,800

Due out in early November, Jet Black continues the series of Japan-themed “young adult” titles that publisher Tuttle started with last year’s Samurai Awakening. Clearly appealing to the global popularity of the Twilight and Hunger Games franchises, this genre is a new one for Tuttle. In JBATNW, the title character is a teenage girl in America with little connection to her Japanese heritage. When her mother dies, she discovers she is the end of a long line of ninja. The action quickly moves to Japan, where she must fight off hired assassins in order to protect a family treasure and ancient culture.

From the Fatherland, with Love

By Ryu Murakami

Pushkin Press, 2013, 672pp, ¥3,059

Often referred to as “the other Murakami,” the Coin Locker Babies author’s work has taken a political slant in recent years. His latest offering begins in 2010, as Japan is hit by global economic decline and homelessness is rampant. North Korea sees Japan’s weakness as an opportunity and sends in forces, while publicly denouncing them as rebels to avoid repercussions. South Korea, the US and China are all too afraid of inciting a full-scale war and so the decision is left to the dithering Japanese government. Like all great works of speculative fiction, it plays on the fears of the day, and since its 2005 release in Japanese, the North Korea situation has received increased media coverage. However, the main political message is a critique of the pathetic indecision of those in power, the ineffectiveness of bureaucracy and the collective malaise of the Japanese people. It makes for a thought-provoking and entertaining ride through a Japan darker than the one we live in.

Evil and The Mask

By Fuminori Nakamura

Soho Crime, 2013, 356pp, ¥1,404

The latest novel by the Kenzaburo Oe Prize winner starts out with a unique premise—an 11-year-old boy is informed by his father that his purpose on earth is to be “cancer,” a role of pure evil that has been passed through his family for generations. He has until his 14th birthday to free himself from his destiny. The tale raises questions about the role of fate in our lives. If we’re destined to do something repellent, can we escape it by acting to cause the opposite effects? This question is memorably asked in Minority Report, though Nakamura goes for a more meditative approach. Through much of the story, the boy contemplates his role in the universe, the morality of his actions and the struggle between nature and nurture. Some of these ideas will stay with you for some time.

A Tale For The Time Being

By Ruth Ozeki

Cannongate Books Ltd, March 11 2013, 432pp, ¥1,198

Ruth Ozeki’s latest starts with a character (based on the author) finding a journal washed up near her quiet Canadian residence. Is it a remnant of the 2011 tsunami? Is the writer of the diary, a 16-year-old Japanese schoolgirl named Nao, still alive? The character and the reader can only speculate. Shortlisted for this year’s Man Booker Prize, the novel features large chunks of information on Japanese culture with over 150 footnotes, many of which long-time Japan residents will find unnecessary. Ruth finds herself wanting verification of the story and the internet plays a vital role in connecting some of the missing pieces. Nao’s narrative illuminates various social problems in Japan, with a focus on bullying depicted in all its harrowing extremes. Her lack of self-pity is what makes her character so engaging, and she is determined not to let the cruelty of others destroy her life.