“There is a downside to this,” Shun says, reflecting on four years as an idol manager. He produces a cigarette. “I started smoking again after five years.”

Outside a grungy Ikebukuro club, where an ‘80s idol tribute night is going on, he has stepped out to relieve some tension, while six performers (none his) are interviewed by a man clutching a Dalmatian plush toy for fifteen minutes.

The crowd here is noticeably more mature than the infamous Chelsea Hotel acolytes. The average age is forty. Everyone came alone and each sits in his personal bubble of adulation, offering their idol an expensive gift or imitating their dance moves.

Once the chat section ends, a girl named Mika strides onto the stage to perform her latest single, ‘Starlight.’ She is Shun’s main asset. He has invested a lot in her and it is evident in the execution; forcing tears at the climax of a ballad, cinematic in her motions, and adept at captivating audiences by making eye contact with as many audience members as possible. Shun commented on this, saying, “She is a rare specimen. A true idol. The others are just singers.”

The lead vocalist for Watarasebashi 43, a local idol group within the category of the independent idol movement, Mika has an agenda to use music to promote her hometown of Ashikaga, Tochigi Prefecture. Shun shares her vision. His passion is tourism and it is why the group exists.

“Her intention is very noble. I hate to say that I’m using her to promote this town, but that’s what she wants, too,” Shun says. “I don’t want to be a producer of local idols. I really would just like to contribute more to the city itself.”

His attachment to Ashikaga began eighteen years ago, when he moved there “by accident,” after getting married. After setting up an English school and publishing a local magazine that promoted local business, his career path changed in 2013 when an Aeon Mall in a neighboring town decided to celebrate its tenth anniversary.

“They wanted to run a campaign for six months that connected the local people. The theme was revitalizing the area,” Shun explains. “I was asked to make three proposals. One was the idol group.”

The mall liked the idea, and auditions were called soon thereafter, but ironically, Shun had an adverse reaction to the positive response. “Out of nowhere, local girls started to appear. Eighty showed up. I realized my mistake. I didn’t have a vision. I thought, ‘maybe I could do this for fun,’ but the girls were so serious. I was embarrassed, but I had to learn how to support them.”

There were two units originally: one for five teenagers, another for kids which had between twenty and thirty members. “Nobody had any experience though. It was horrible. The girls didn’t have talent, couldn’t sing or dance, but they had hope. How could I betray that?” The six months originally intended as the project’s lifespan were given over to rehearsals.

Merging the groups to make one unit of ten, aged between six and seventeen, this new incarnation went public. However, by this stage, the mall was not funding the project. “We tried selling photo sessions, but nothing covered the costs,” says Shun. “The Japanese government used to give out so much money to idol groups. Then there was the 2011 Earthquake. Now, it is hard to get ¥50,000 from local governments.”

In order to secure funding from local boards, Shun needed to develop a stand-out pitch. This he did, which brings us back to Mika’s show in Ikebukuro.

While describing her personal ambitions, Mika lights up, never seeming to blink or break eye contact. “I simply wanted to promote my hometown. It was not about wanting to be an idol. Our songs reference the community, so I am contributing to the town. I want to introduce the audience to the sceneries and the stories. This is my latest single.”

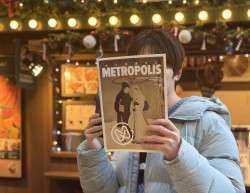

Shun proceeds to present me with two items, his magazine and a CD.

Inside the magazine is an interview he convinced Mika to conduct with a former Minister of Economics, Trade and Industry. “We didn’t get money, it was publicity,” says Shun. If he wanted to be a cultural representative, this was a brilliant stamp of approval, and it ended up earning the group status as a cultural ambassador for the prefecture.

Then, drawing my attention towards the CD, Mika says, “This came fourth in the daily charts.”

Then Shun adds with a wry smile, “Well, we cheated. Everybody does it.”

The national charts, Oricon, are synonymous with cheating on all levels. It is an easy system to manipulate, which is fortunate, since you probably won’t rank unless you are willing to game it. Outside making the number one spot, breaking into the Top 30 is a solid target, since it guarantees airtime on national TV and radio.

“AKB48 has a saying: one album is equivalent to five seconds shaking hands,” Shun says. What he means is that one can encourage fans to buy in bulk by guaranteeing a gimmick on the other end. The other prevalent method is to have a distributor agree to inflate the number of sales when entering them into the data.

Nothing in the independent scene is lucrative, so it is a necessity just to avoid going under. “Something has to be there to persuade the town and prefecture to help. I use these tactics for recognition. I found a chance with Oricon, so for someone who doesn’t know about it very well, number four sounds good, even if you’re using people to bring up the results. I just want people to recognize them and say ‘look, they are doing so well.’”

Whichever way Shun decided to game the charts, he wants to emphasize how personal gain is not the objective. He doesn’t need to say this outright, because when I bring up the fact that Mika performed in Hawaii a few months earlier, he reveals a paternalistic facet in his managerial duties, wherein he would do anything to make her happy.

“I had this ambition to go abroad with them. I wanted to see the world, as if looking through the eyes of their fathers. 50 percent of the funding came from my pocket. I don’t know how I did this. It was to show them that it could be done, to get better funding, so we could take Mika again. The next one could be entirely from my own pocket, but my duty is to give good memories.”

The last time we met, it was in a plush hotel dining room overlooking Ashikaga and the Watarasebashi Bridge. Twenty tables were set for guests, parents and fans to indulge in an eight-course meal, while Mika strode between each group with her usual gravitas.

In between sets, other sub-units were brought out, consisting only of members below the age of ten. They were unmistakably adorable as they freaked out to the tune of tinny, pop-rock backing tracks, while Shun hung behind a curtain in a state of anxiousness. Things had been good, but there had been no significant advances in some time. So, this was probably going to be one of the group’s final outings.

He was even more despondent later that evening at their second show, in a rockabilly punk club. Under the pretense of a surprise birthday party for Mika, he screened a retrospective video of the group’s development over four years. Narrating this compilation, as the kids were cheering with joy, he spoke from behind the sound desk like a proud father — but once out of the spotlight, his face read “End Times.”

One month later, the Hawaiian state government contacted Shun. They wanted Mika to perform in the US regularly, as part of a larger, official cultural exchange. Speaking over the phone, for the first time since we met, Shun actually sounded happy. “It’s still not easy, but now I see only the lights. With Hawaii, the journey can go on.”