Katsura Sunshine

(Photo by Julio Shiiki)

“I could go to any master in the rakugo world and say, ‘I’m Bunshi’s deshi. My name is Sunshine. I love the way you do this story. Will you teach me?’ And they will teach you.”

This, says Katsura Sunshine, is a core benefit of spending three to four years in apprenticeship to a rakugo-ka, a professional performer in the traditional Japanese art of comic storytelling.

“Think of going to Bill Cosby and saying, ‘I’ll clean your room for three years if you give me the name Cosby and let me open for you, and teach me your comedy acts, and let me do some of your comedy acts, and let me introduce myself as your apprentice. And then all your fellow comedians, if I ask any of them, you’ll let them teach me some of their comedy and let me use that as well for my own shows.’ You’ve got to be crazy, right?”

Yet in 2008, Sunshine did exactly that. In that year, Osaka Rakugo Association President Katsura Bunshi VI, then known as Katsura Sanshi, took in a 182-centimeter, blond-haired Canadian playwright named Gregory Robic. Within about a month, as per tradition, Sanshi gave his apprentice his own family name and part of his given name, thus creating the performer Katsura Sunshine (“Sunshine” is written as 三輝, or “three sparkles”). He is the first foreign professional rakugo storyteller since Kairakutei Black of the Meiji era, and the first foreign-born professional in the 400-year history of Osaka’s kamigata rakugo style.

Rakugo developed independently in Osaka, Kobe and what was then Edo, now Tokyo. While the Edo style focused on o-zashiki—closed houses before an anonymous audience—the Osaka tradition was born on the busy streets of the merchant city. Storytellers would set up a low table, banging on it as they announced which famous story they were about to perform. These classic tales, called koten, are still performed today, along with an ever-growing repertory of sōsaku rakugo, or new rakugo.

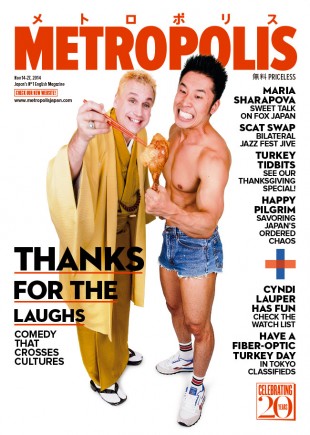

Katsura Sunshine and Nakayama Kinni-kun on the cover of Metropolis #1077 (Photo by Julio Shiiki)

A modern rakugo performance is typically divided into a makura (literally, “pillow”) and hon-dai (main story). The makura, Sunshine explains, is nearly identical to a Western stand-up comedy routine. “You do your own material, you address the audience directly,” he says, talking a mile a minute with optional punctuation. “So you introduce yourself. Basically, you’re trying to get the audience to like you. And you’re also trying to get the feel of the audience to know which story to tell them.” The more experienced the storyteller, the longer the makura.

The makura also acts as a bridge into the main story. The storyteller might, for example, lead into the classic tale of a man who gets a job wearing a tiger suit at a second-rate zoo by discussing his own trouble getting work—or, as Sunshine does, introduce a sobering discussion of death just before a character arrives at the afterlife’s unhelpful customer service window. Guessing the story, he says, is part of the fun.

The story starts unannounced, with no further introduction than perhaps a knock at the door punctuated by the kon-kon-kon of the storyteller’s sensu fan on the table. The moment represents a seamless transition from stand-up (or rather, kneeling) comedy to tightly controlled physical theater, each scenario brought to life through nothing more than the deft choreography of body language and vocal intonation. Aside from his fan, a rakugo-ka is only allowed a tenugui hand-cloth as a prop—but connoisseurs will also watch for the dramatic moment when the performer removes his haori, or overcoat. Each story then concludes with an ochi, or punchline, often predicated upon a cleverly set-up pun.

Katsura Sunshine with Nakayama Kinni-kun (Photo by Julio Shiiki)

By the mid-1990s, the man who would become Sunshine was already a successful playwright in Toronto. His musical adaptation of Aristophanes’ The Clouds had run in the city for 15 months prior to a cross-country tour. He came to Japan in 1999 to examine the traditions of Noh and Kabuki, which he learned had structural similarities to classical Greek theater.

He would find his true calling not in the universities where he taught drama for five years, however, but above his local yakitori shop, where one day the master invited him to an evening of rakugo after closing. Watching the performance, Sunshine says, “That just hit me. Like, this is it: This is what I was born to do.”

Tying his accordion skills to a few Japanese jokes, he offered himself as an interstitial act in day-long rakugo sessions at Tokyo’s traditional yose theaters. As one performance led to another, the storytellers he worked with suggested he simply learn a few stories and market himself as a foreign rakugo-ka. But Sunshine was entranced by the samurai-like tradition and formality of the dressing room, where one’s rank determined everything from order of appearance to who poured tea for whom. Watching the professionals, he says, “Each one had this certain something. And I was positive that they got it—it’s their manners, and their way of addressing the audience, and just their way of existing—I was sure there was something they got from three years or four years of shugyō (apprenticeship) that I’m not going to get just by getting someone to spend an hour with me to teach me a story and learning the moves.”

Katsura Sunshine performing for the CCCJ

(Photo by Mike Kanert)

It took eight months of importuning before Katsura Bunshi (then Sanshi) would take him in. Sunshine describes the subsequent four years of total subservience as a debt he can never fully repay.

From the outset, Sunshine was convinced his master’s repertory of original rakugo stories could work in English—or in any language. Even the makura, he notes, is almost identical to any other form of observational comedy. “But once you put the kimono on and say, ‘Hey, my name is Sunshine and this is the kind of apprenticeship I did to get here,’” everything changes, and audiences become intrigued.

In 2013, he tested his theory with a tour of 20 North American cities. He’s now told English versions of rakugo stories on Canada’s CBC and CTV television networks, and this year spent the summer at Scotland’s Edinburgh Festival Fringe. As he works on a world tour, his dream is to have a long-running rakugo show in London and New York.

“The reason I think there’s a market for it abroad is because rakugo is very, very, very clean humor. A rakugo storyteller never wants to alienate any part of his audience. So it’s not edgy. It’s the opposite of edgy. It’s like Bill Cosby.” And it’s also drop-dead funny. Parents thank him for allowing them to laugh out loud for 90 minutes alongside their kids.

Sunshine is now hoping other foreigners will follow his example, and he’s excited about the possibility of someday taking in apprentices—or deshi—of his own. “Just give them a name, do the whole thing—I’d love to,” he exclaims. “I can’t wait.”

And he promises it’s not just because he doesn’t like folding his own laundry.

Katsura Sunshine will be appearing in London, Manchester, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Oxford, Ljubljana and Paris over the next month.