In many ways, a camera is a clock: a device that measures time, both when it takes pictures, with its shutter opening for specified lengths of time, and by the nostalgia generated by the images created. At least that’s the premise of “Time Present: Photography from the Deutsche Bank Collection” at the Hara Museum of Art.

The name of the show is a potent pun, referring to the present moment, but also implying the presence of time throughout the diverse selection of works that make up this show. This curatorial selection of works has travelled to several venues and is divided into four sections. But this may not be apparent when you visit the Hara, as the show has been remodelled to fit the museum’s unique art deco spaces.

Of the four sections, the most impressive is “Time Exposed,” which includes work by two important Japanese photographic artists, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Tokihiro Sato, and several Germans, including Sigmar Polke, who is mainly remembered as a pop art painter.

Polke’s two works, both called Uran (1996), are simply the photographic plate exposed to the natural radioactivity emitted by uranium, reminding us that the ultimate clock we have is measuring the decay of radioactive isotopes.

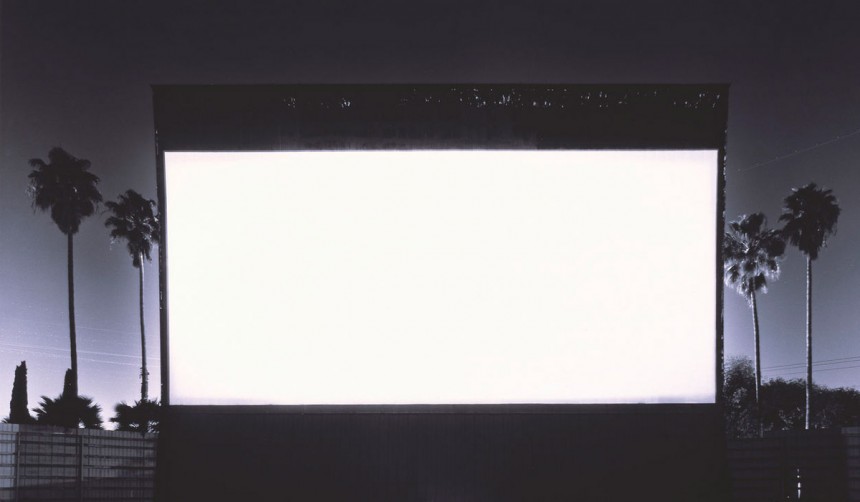

Sugimoto’s Rosecrans Drive-In, Paramount (1993) is a shot of an entire movie taken with just one very long exposure, reducing the movie to a white rectangle of light—the images having cancelled each other out to create something transcendent. The only problem, however, is that the actual works produced by the conceptual cleverness of Polke and Sugimoto are rather sterile.

Much more effective in terms of aesthetics and also concept is Tokihiro Sato’s “respiration” works. Using the same kind of incredibly long exposures as Sugimoto, Sato is present before his own open lens but remains invisible, as he never stays in one place long enough to show up in the final images. The only signs of his presence are flashes of light—symbolic of breaths of air—that he shoots into the camera from time to time, which register as little stars, giving Sato’s work an almost fairy-like quality.

The next section, “Today is the Past,” focuses on photography’s ability to capture the moods of the past. Boris Mikhailov’s sepia-toned shots of holiday-makers in the Soviet Union in the 1980s, and Liu Zheng’s more recent shots of China, remind us that the past is another country.

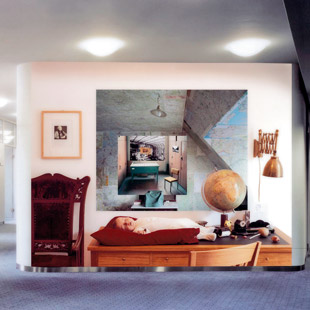

Most visitors will be baffled by Gerhard Richter’s Sechs Fotos (1991), blurry selfies of the photographer/painter moving ghostlike around his room. The photos, however, are a cryptic reference to the three members of the Red Army terrorist group who were found dead in their cells at Stammheim Prison in October 1977.

The section “A Moment of Intense Concentration” is a reference to the “decisive moment” that the famous French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson talked about. But most of the images here—mainly street scenes of varying interest—would be just as good taken a few seconds before or a few seconds after, rather disproving the point.

Overall, this is a thought-provoking exhibition, but one suspects that more time could have been put into its preparation and the selection of images.

Hara Museum of Art, until Jan 11.