February 19, 2009

Tokyo 2050

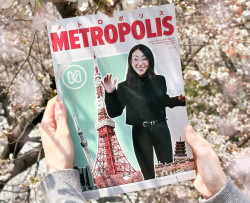

Futuristic super-hub or graying has-been: what's next for our favorite metropolis?

By Metropolis

©Trevor Eccles

The emergence of China and India and their economic capitals, Shanghai and Mumbai, is an obvious challenge to Tokyo’s role in the region. But their dominance is not inevitable, and Tokyo has a card that they’re unlikely to be able to trump: livability.

Last year, Monocle magazine, an arbiter of both sense and taste, placed Tokyo third on its list of most livable cities, behind Copenhagen and Munich. But speaking about those two metropolises in the same breath as Tokyo is like comparing a couple of shiny apples with one huge, over-polished, genetically modified orange.

“Tokyo is three times the size of most comparable cities, but has an infinitely better infrastructure than any of its rivals—Paris, London or New York,” says Monocle’s Asia Editor, Fiona Wilson. “Better public transport, better-behaved citizens, less litter, less crime; it’s full of people but manages to be quieter somehow. The aggression that characterizes even small encounters in many large cities is just not an issue here. It’s not perfect—no city of this size could be—but it’s hard to imagine any other city functioning as well with so many people.”

Indeed, Tokyo prides itself on livability. What the Bhutanese termed Gross National Happiness, Tokyoites might call Gross National Convenience. But convenience is not enough if the city wants to be more than a New-Generation Disneyland.

“Japan can make the greenest cars, the fastest trains, and have the cleanest streets, but ultimately what does it matter if there isn’t anyone here to run the place?” asks Fall, whose company has recently completed a research project into the world’s most innovative cities.

Japan will soon be losing a million people a year and the population will shrink from about 128 million today to less than 100 million by 2050, according to Cabinet Office projections. And forty million of those people will be over age 65.

“If you’re trying to build a dynamic economy, you can’t have more than half your team on the bench,” adds Fall.

Some politicians and pundits don’t see a problem. Labor shortages will be less of an issue as robots take the roles of nurses, receptionists and cleaners. Yet others realize that they are missing a vital ingredient to maintaining its status as a world leader, one that can be summed up in a two words: creative fission.

London, January 15, 2009, 11am: It’s the middle of the worst economic calamity in 60 years and commuters look glum as they arrive for work in the City of London, ex-financial capital of the world. Thousands pass through the vaulted Victorian concourse of Liverpool Street station every hour. For most, it’s the start of what looks like a horrible business year.

Suddenly, a voice sings out over the speakers: “You know you make me wanna shout!”

As the Little Richard ’60s classic booms across the station, a few people start to dance in unison. Each time the music changes—to The Contours, Yazz and the Plastic Population, and even The Pussycat Dolls—more and more passersby drop their briefcases and start to groove.

“Don’t you wish your girlfriend was hot like me!”

Suits are grinding and grannies are laughing, while hidden cameras record every jive and smile.

After 120 seconds, as fast as it started, the music cuts, the dancers pick up their belongings and normalcy returns.

“The train now at platform 12 is the 11:07 stopping service to Norwich.”

What just occurred was a “flash mob” advertisement by Saatchi & Saatchi for the mobile phone company T-Mobile, screened on prime time TV the following evening. The agency planted 350 dancers in the station to turn it into an impromptu disco.

This is the sort of creative freedom that Tokyo lacks—and exactly what it needs if it wants to maintain its edge.