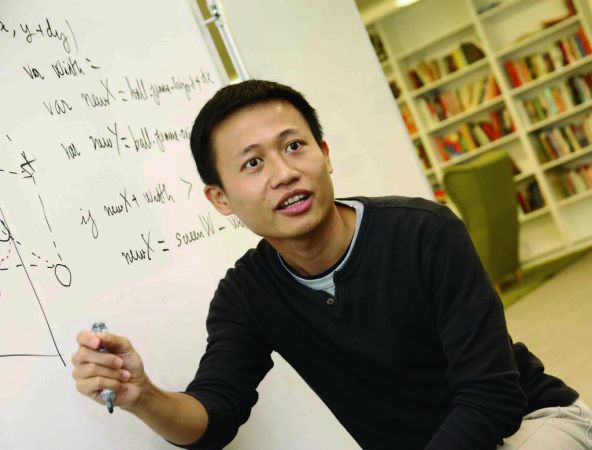

My story is very simple,” Duc Doba begins. “It’s pure luck, from my point of view.” While his success might be in part thanks to a series of good fortunes, Doba’s journey to becoming the founder CEO of IT consulting start-up Tokyo Techies is one propelled by relentless ambition. It’s an ambition fueled by his own entrepreneurial fire, as well as a greater trend in Southeast Asia: tech workers striving to be valued more than the low-paying, outsourcing contracts they so often settle for.

Japan—despite being the third-largest economy and boasting a long history of technological innovation and entrepreneurship—arguably remains a challenging environment for foreign start-ups to penetrate, due to linguistic, cultural and bureaucratic barriers. Nonetheless, Doba demonstrates how adhering to values of synergy, agility and trust cultivated by his cultural roots in Vietnam have made it all possible.

FROM THANH HOA TO TOKYO

Before Tokyo Techies, Doba was a self-starter student in Thanh Hoa, Vietnam. Located just below Hanoi, Thanh Hoa was devastated by the war but boasts the best high school in the country. Growing up, he didn’t have enough money to buy his own books; instead, he would head to the local library to study.

“Back home, people are hungry for more,” he says. “People are so excellent at learning. When we seek employment, we reach for the top.” Nurtured in a competitive educational environment thanks to his parents’ careers as teachers, Doba was encouraged from a young age to join contests—singing, writing and later programming.

“Even now in consulting projects wherein the customer must select among multiple vendors, I picture it as joining a competition by default,” Doba says. “Whenever I do something, I want to be the best.”

During his second year studying IT at the Vietnam National University of Hanoi, he was one of 10 students selected for a Japanese training scholarship granted by the company AXISSOFT. It was here that he learned Japanese and connected with a Japanese benefactor, who recognized the aspiring entrepreneur’s potential and granted him a job offer in Tokyo.

I want to show that even if we are from Southeast Asia, it doesn’t mean you can pay only a third of the standard cost.

In his 14 years here, Doba has attained a high-profile status with some of Japan’s premier tech companies, coasting through managerial and engineering positions in Rakuten, LINE and SoftBank.

However, these large corporations felt limiting. Employees follow rigorous frameworks when it comes to technical debate—layers and layers of approval—and Doba was usually met with resistance when he proposed overly-innovative solutions. Criticisms along the lines of: “You’re a foreigner, you don’t understand,” were not unheard of. At 30 years old, he hit a turning point. Rakuten and Softbank presented comfortable compensation packages—and he took them.

THE RISE OF SOUTHEAST ASIA

“My passion cannot be complacent,” Doba says firmly. “We bring a new sort of energy to the whole society in Japan.” With a cultural background that emphasizes togetherness and trust in the human experience, Doba understands the power of inspiring others, and the greater overall value derived from working with a group.

Thus, in 2017, Tokyo Techies was born. It was originally an IT training company before progressing into consulting and product development for data science, AI, cyber security and cloud building.

Doba believes the Japanese work environment has room for failure without committing one’s assets. He sensed cultural similarities between Vietnam and Japan, including being strict with oneself. Leverage the platform you’re already in, and observe the corporate environment. “Learn from their failures,” he says, “not their successes.”

Remembering my living conditions growing up keeps me grounded, and having started from the bottom equips me in adapting to tough situations

While teaching may be his first passion, from an IT expert’s perspective Doba was conscious of the lack of resources for specific skill sets within Japanese companies.

According to the Ministry of Justice, foreign technical interns in Japan in 2016 were predominantly from Vietnam. Southeast Asians in tech often settle for outsourcing contracts, with no career ambition beyond completing their required hours. However, Doba believes that products need constant development—persevering with both brain and heart.

CREATING A CULTURALLY AND ETHNICALLY DIVERSE COMPANY

Currently, Tokyo Techies employees are 92% foreign, hailing from Nepal, India, Indonesia and more, with a company ethos emphasizing that foreign workers champion new perspectives, experiences and values.

“Remembering my living conditions growing up keeps me grounded, and having started from the bottom equips me in adapting to tough situations,” Doba says. “The larger business value in Japan allows me to grant more opportunities to others as well.”

Despite the tough industry competition, Doba prioritizes providing clients with real value. Cost-saving attitudes—such as outsourcing—may be cheaper. However, he holds strong to Tokyo Techies’ core values of quality and agility.

“Aside from not being Japanese, what’s difficult is presenting traits that Japanese people don’t feel aware of, since the market is designed that way.”

Thus, Doba enables his employees to work remotely, from anywhere in the world. He believes the value is not in one’s location, but the final output— and, therefore, provides overseas employees the same service fee that is standard in Japan.

Tokyo Techies often charges higher for services compared to other Japanese companies. “I want to show that even if we’re from Southeast Asia—it doesn’t mean you can pay only a third of the standard cost. We can charge more because we’re a skilled company, composed of skilled individuals who are quick to adapt and provide solutions for the same problems.”

VOLUNTEER, FRIEND AND LEADER

Doba traces his leadership style back to his experience volunteering in his home country, leading the Vietnam Youth and Student Association in Japan (VYSA). Today, he continues with charity activities to send profits to underprivileged children in Vietnam.

“I know that in the future, good will return to me,” says the CEO. “I invest in the actual, personal condition—not on-the-spot cash value.”

The startup doesn’t quantify the projected amount of revenue as a measure for future success—but instead, as one seeing that his employees, whom he refers to as his friends, are enjoying their work, staying with the company, and trusting the friendship will continue.

“We give. We keep giving. We don’t just give and take.” He encourages the same for Southeast Asians in Japan: to be confident in presenting one’s value, to find opportunities outside of work, to volunteer, and to surround oneself with self-motivated people.