September 25, 2015

Cleopatra and the Queens of Egypt

The Tokyo National Museum reflects on the women of the Nile

One of the most fascinating historical figures is undoubtedly Cleopatra. She was the Queen of the Nile, the lover of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, a sex symbol, and a tragic heroine who ended her life using the unusual method of a snake bite.

If you have an interest in ancient Egypt, she’s probably a large part of the reason why—although, of course, she wasn’t actually Egyptian, being part of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled the country for 300 years after the death of Alexander the Great.

(© Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels)

She’s also the focus of Tokyo’s latest big exhibition on ancient Egyptian artifacts, “Cleopatra and the Queens of Egypt” at the Tokyo National Museum. But perhaps “focus” is the wrong word, as there are still several veils of mystery that separate us from her legend.

One obvious example is her actual appearance. The exhibition includes two incredibly detailed busts of her two famous lovers, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. Caesar has a lean, muscular face, while Mark Antony is large and imposing with a distinctive nose. But there’s no reliable likeness of Cleopatra herself, rather just some non-descript statue heads “attributed” to her, without any real proof.

Ironically, for a woman famed more than most for her looks, her appearance may not have been central to her charm. The most authentic account of her we have is that recorded by the Greek biographer Plutarch in his famous Life of Antony, written around 200 years later. Plutarch emphasizes her conversational abilities: “For her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her; but converse with her had an irresistible charm.”

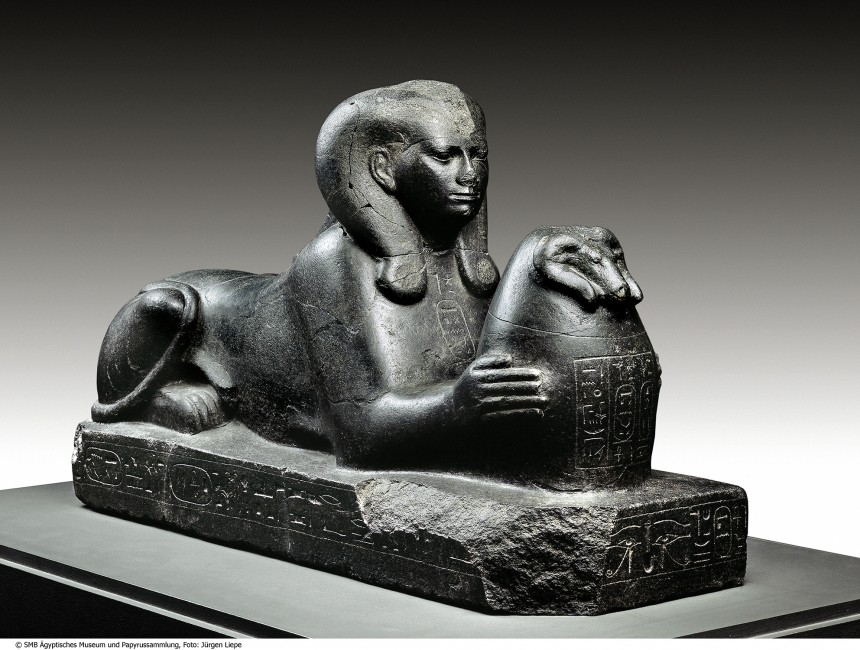

If anything, this qualifies her to be a feminist icon rather than another “objectified” woman. But although there’s a lack of clarity about her actual looks, there’s a certain iconic myth about her that essentially draws from the ancient Egyptian iconography of beauty, which is as exotic and potent as the sphinx.

In the absence of an actual Cleopatra, we fill in her image with the age-old elements of Egyptian beauty. The elaborate headdresses, the figure-hugging flowy dresses, and the rich perfumes and makeup—including the heavy eyeliner—create our imagery of Cleopatra, as the 19th-century painters included in the exhibition did.

This aspect justifies the exhibition’s inclusion of earlier centuries and personalities, like the sylph-like daughters of Amenhotep III from 1,350 B.C., carved in relief; or the statue fragment of Hatshepsut, another powerful queen from the 15th century B.C.

But even though queens were revered as goddesses and exemplars of beauty, Egyptian ideas of their beauty remained far from spiritual.

A poem from a stele in the Louvre includes this sensual description: “The daughter of the king, sweet of love, is the most beautiful woman. Her hair is darker than the gloom of night, than grapes, than figs; her teeth more finely arranged than the notches of a flint blade; her breasts, firm, rise on her bust.”

This is how we still like to imagine Cleopatra, despite her brilliant mind and winning personality.

Runs until September 23. Tokyo National Museum.