April 19, 2018

Hello World, Hello Now

Does technological advancement really bring about joy and satisfaction?

By Nick West

The future is here. It has been two decades since the internet first emerged. “Algorithm” is now a familiar word, being entranced by hand-held devices is commonplace and adverts for virtual currencies insinuate themselves into the physical world. Technology redraws the world anew. “Hello World – For the Post-Human Age” is a group exhibition by artists from Japan and overseas that looks to art as “an early alarm system” to alert us to where we are, and what we are likely to face, in the hereafter.

Taking its title “Hello World” from a stock phrase used to test the installation of programming software, Junya Yamamine curates this exhibition at Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito in Ibaraki. The show’s graphic design also reflects this media, with typography assembled from a raft of underscores and backslashes. What begins with code, ends with social media, artificial intelligence and more.

Whereas exhibitions that address technology usually celebrate what innovation brings, Hello World casts a critical eye over recent developments and asks us to evaluate whether these advances inspire promise, apprehension or dread. Most of the artists included are in their thirties. Collectively, the show could be read as an essay in which each room addresses a particular aspect that technology ushers forth – be it freedom, topography, intimacy, money or social validation.

The term “Post-Human” is an idea rooted in science fiction, futurology and philosophy. It refers to the notion that a person or entity that exists in a state beyond being human. David Blandy’s Tutorial: How to Make a Short Video about Extinction (2014) embraces the possibility of human annihilation following a storm of meteorites. Blandy’s work may seem like a bleak joke without an obvious audience, but it serves to show how easy it is to simulate the earth’s destruction while attuning us to an era beyond ourselves.

In fact, Blandy’s work is one of several instructional videos on display. These attempts to explain new forms in straightforward terms suggests that we are grappling to understand what we have created. Not that the tone of all these works is pessimistic. Simon Denny’s What is Blockchain? (2016) is an informative way to unpack crypto-currencies and Hito Steyerl’s How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013) illustrates how we can lose ourselves to technology while watching a video about cloaking tactics.

Steyerl’s How Not to be Seen is shown after a set of optical equipment and an abstract arrangement of white vinyl tape is laid out on the floor. Carefully steering visitors through a stark installation before presenting the video, the only color glimpsed is the green of a green screen. A projector beams, lessons begin. A variety of tactics to evade sight are listed. Narrated by an artificially modified voice is a game of hide and seek. The abstract arrangement of vinyl tape is explained as a resolution target, which was a way of testing optical imaging employed by the U.S. Air Force. Located in the Californian desert, these physical targets were introduced to calibrate analogue photography before being superseded by digital technology.

As the lessons continue, the seriousness of the voice-over gives way to digital pixelation, and offers increasingly more playful ways not to be seen until the analogue world is plagued by rogue pixels. Unlike the aloof presentation of optical equipment in the first gallery, How Not to be Seen is surprisingly amusing, a work whose humor stems from a misplaced importance in any one form of technology.

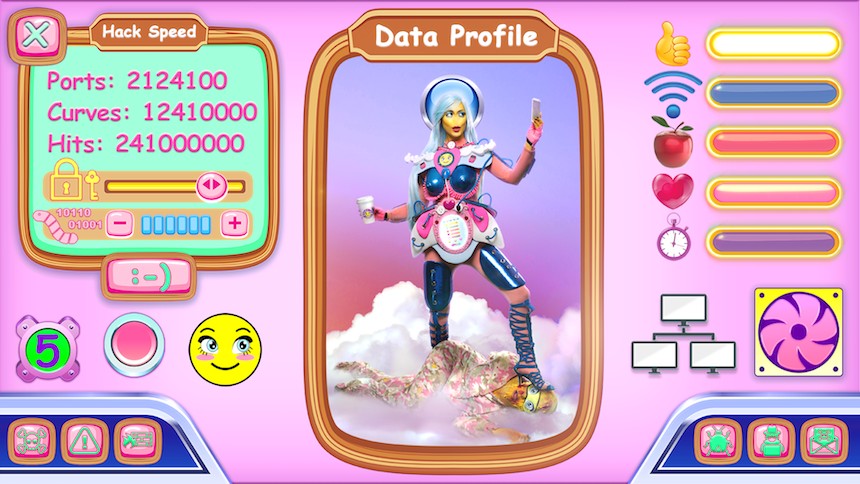

Another piece of work that uses humor, albeit darkly, is Rachel Maclean’s It’s What’s Inside That Counts (2016). As a 30-minute furore that critiques our growing dependency on social media, this video is crammed with emojis and Comic Sans typeface. Impressively, it is performed by the artist alone. The colors are lurid and enhanced. It doesn’t attempt to be slick but is exaggerated and compelling. The characters don’t have noses as the story takes place in a scentless domain. It describes the descent of a happy and attractive, although deeply narcissistic woman who fails to achieve the social validation she craves online and so unravels to become fat, hairless, but worst of all, unpopular. Described as “a Kardashian-type Demigod, more cyborg than human”, her fall is accompanied by the need to consume a steady stream of coffee, a drink as essential as an internet connection.

Maclean’s video is made from groups of characters. One group are rodents, small and hairy with bulging cheeks and pointed teeth. Then there are the feeders, who demand data. They wear sleeping masks and their skin is splattered with goo. And finally, there is the antagonist, a bald-headed man who levitates aloft a giant dimpled sphere, a bit like a golf ball, who calls for calm like an Eastern mystic. He represents contentment, the antithesis of the main character’s anxiety-riddled existence.

Beneath Maclean’s imaginative visuals is an artwork that dramatizes some of the dynamics at play when we participate in social media by examining the relationship between the reality celebrity star and their followers. It’s What’s Inside That Counts amplifies what it means to seek popularity online as a product for consumption. Although dystopian, it is easy to relate to and very much of its time.

Which is why the exhibition works so well as a whole. Hello World could have been a sleek tribute to technology if it weren’t so relevant. It’s an intelligent show that asks questions about how entangled we have become with the devices we use by understanding how we use them. The most engaging works were those that were humorous, those that were ugly or daft, or the most human. If art is an early warning system, this group exhibition in Ibaraki is one worth taking notice of. The future isn’t what it used to be.

Featured image credit: Hito Steyerl, “How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File” (2013) Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York. Image CC 4.0