Ryushi Kawabata, one of the most acclaimed Japanese painters of the 20th century, was obsessed with dragons. These long lithe mythical beasts, associated more with water than fire in Eastern legends, are everywhere in his art. Sometimes taking center stage as full-bodied scaly creatures, but more often appearing as no more than hazy outlines within a puff of smoke or the foaming waters of a raging river.

This love of dragons was evident from a young age. Kawabata*, whose birth name was Shotaro, first moved to Tokyo in 1895 from the rural prefecture of Wakayama when he was 10 years old. Initially intrigued by poetry, the young boy soon gravitated towards painting, which he first studied in Japan and later the United States. As his work continued to gain more recognition, Kawabata adopted the name Ryushi, which contains the kanji for dragon (龍, ryu), as his nom de plume.

One Kawabata dragon could be seen on the ceiling of the main hall in Asakusa’s Sensoji Temple until 2023, when it shocked tourists by peeling itself off the wood it had been attached to for decades (restoration efforts are currently ongoing). Another, the last dragon that Kawabata ever painted, can still be seen on the ceiling of Honmonji Temple (near Ikegami Station in Ota-ku). Kawabata actually died before completing this work, but somehow the dark background and large globular white eyes are evocative enough on their own.

To get a fuller sense of Kawabata’s work, however, as well as his life, I recommend a visit to the Ryushi Memorial Museum, about a 10-minute walk from Honmonji or 15-minute walk from JR Omori Station. Kawabata actually paid for and designed the museum himself, installing features such as raised floors to protect against flooding and humidity as well as large windows to allow his paintings to be viewed in natural light (these have since been shuttered to protect against long-term damage to the artwork). Rocks, plants, and other decorative elements around the museum were brought in from Shuzenji on the Izu peninsula, where Kawabata had a beso (country house). Best of all, when viewed from above, the building itself resembles a long, curling dragon.

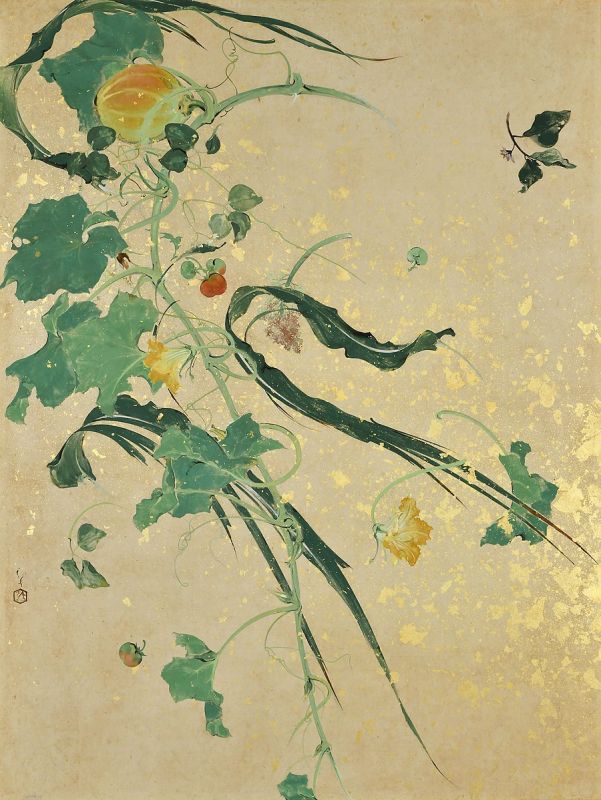

Because Kawabata was so prolific and his paintings so large, the museum houses constantly rotating exhibits to showcase different examples of his work. Kawabata traveled extensively throughout Japan to sketch and paint many of its architectural and natural wonders, and much of his painting tends to focus on Japanese nature or mythology, or a combination of the two.

His painting was not, however, unaffected by the 20th-century world he lived in, as visitors can learn in a tour around the artist’s former house, studio and garden. Located immediately across a sakura-lined street from the museum, the grounds of Kawabata’s former home are open for daily tours at 10:00, 11:00, and 14:00. Some of the guides can speak English, though they say they get relatively few visitors from other countries.

The building that now stands on the property is actually the second house Kawabata built there. The artist’s first home was destroyed by a bomb in an air raid on August 13, 1945, just two days before the end of World War II. The bomb crater can still be seen in front of the house in the form of a pond ringed with wild plants, which Kawabata allowed to proliferate to reflect his love of nature over the manicured perfection of conventional Japanese gardens. The shock of having his home obliterated prompted Kawabata to respond immediately in paint, producing one of his most famous works, Bakudan Sange, an abstract depiction of flowers and foliage blasted apart by the bomb.

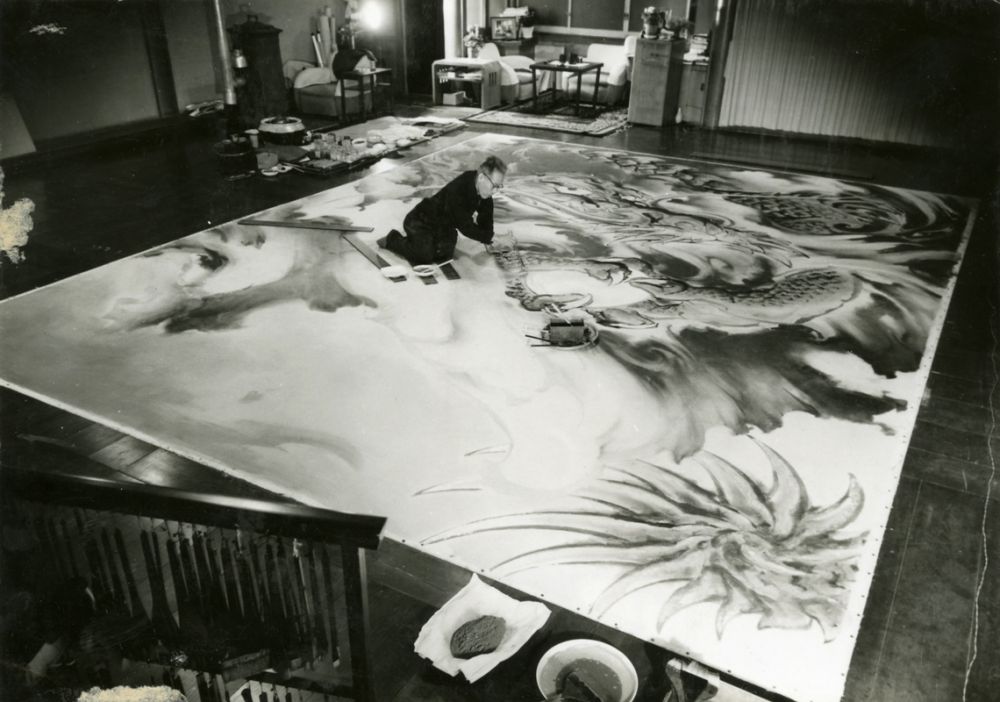

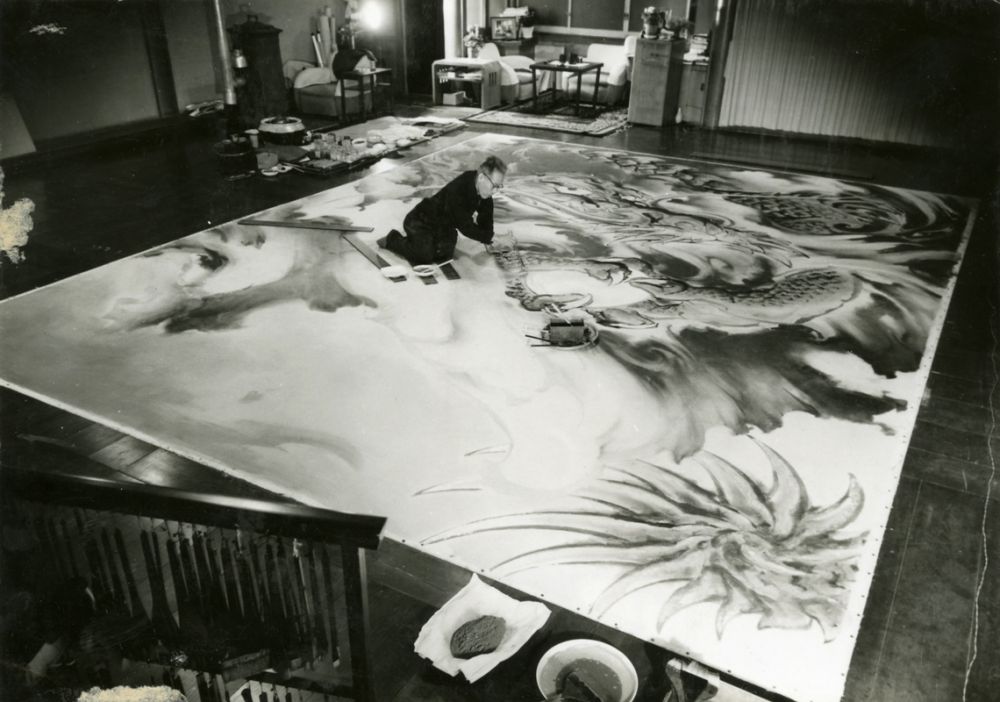

The house itself is a beautiful example of traditional Japanese architecture, though it too is highly personalized. Some of the woodwork is designed to resemble the scales of a dragon, along with many other clever touches that your tour guide will be only too happy to point out. Behind the house is Kawabata’s spacious studio, laid out in 60 tatami mats to accommodate his huge paintings and featuring windows that prioritize sunlight from the south (he apparently disliked light coming in from the west). Kawabata built this studio in 1938 and worked there until his death in 1966. Some of the older people I’ve met around the neighborhood even remember meeting him when they were children.

Now, I’ll confess that I’m no art aficionado. Far from it. Large art galleries tend to tire me out or bore me (I tend to prefer history museums). My knowledge of Japanese artists up until I visited the Ryushi Memorial Museum was limited, like many, to the ubiquitous ukiyo-e prints of Hokusai. And yet, I found the combination of this small museum in Ota-ku, with its huge impressive paintings (and huge impressive dragons), and the former home of this fascinating man to be one of the most intriguing places I have visited in Tokyo in a very long time.

Many readers may be familiar with Yasunari Kawabata, the Literature Nobel Prize-winning author of Snow Country and Thousand Cranes. The two men were not related but Yasunari actually lived just up the street, about a five-minute walk from the Ryushi Memorial Museum. The house he lived in is no longer there, but a small plaque stands in tribute to the great writer

All photos courtesy of the museum