Stanley Kubrick’s seminal film 2001: A Space Odyssey presents a particularly powerful vision of mankind’s trajectory because it so brilliantly simplifies. The classic moment in the film, in which the entire history of mankind is encompassed in a single jump cut between an ape throwing a bone up into the air and a space station spinning around in space, has become legendary.

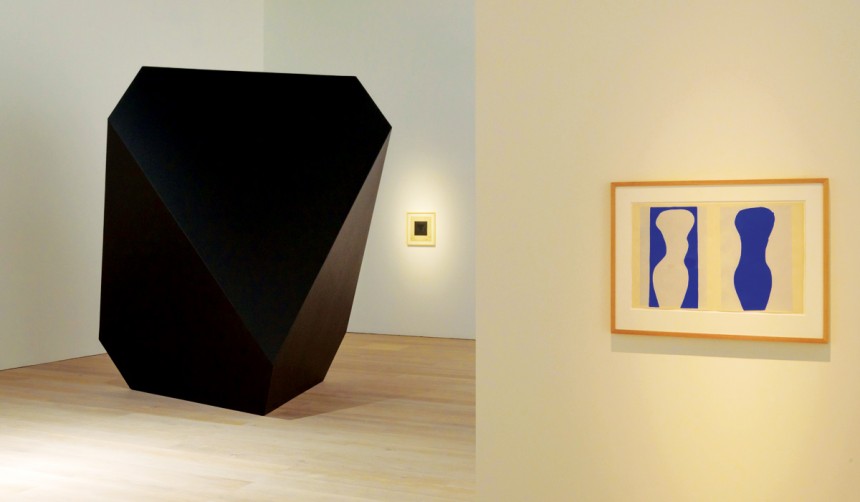

A similar sense of aesthetic compression and reduction to the essentials infuses “Simple Forms: Contemplating Beauty” at the Mori Museum of Art, an exhibition that has been honed down to basic geometric figures or biomorphic shapes that evoke our ancient ancestors’ first experience using stones as tools.

Ahrenberg Collection, Switzerland

A key work is Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco’s Boulder Hand (2012), a short video installation made with an iPhone. It takes a similar leap to Kubrick’s famous jump cut, but instead of a bone and spaceship, Orozco’s piece shows us the affinities between the handling of a stone tool and the handling of a smartphone. The video shows a hand rubbing a stone in a way that puts us in mind of how we rub and swipe our phone screens.

Helping to reinforce this point is the presence of a piece of flint, crafted into a blade from the Solutrean Period (22,000-17,000 B.C.), and a selection of sculptures by Brassaï, the pseudonym of Hungarian artist Gyula Halasz, who was fascinated by primordial forms.

In a similar vein, modernist minimalist sculptures by the likes of Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Jean Arp, and Constantin Brancusi are also included. The latter draws our attention to the surprising absence of Isamu Noguchi at this exhibition. Noguchi was a pupil of Brancusi’s, and in the planning stage would have been an obvious reference point for an exhibition of this nature in Japan.

Besides this minor quibble, the main problem the exhibition has is that it appeals more to the tactile than the visual sense, but with the usual proviso that nothing must be touched. In visual terms, there is a certain bleakness and sterility to the show, with monochromes, geometric shapes, and parsimonious curves dominant.

Apart from sculptures and a number of installations, like Anthony McCall’s flickering Cinematic Installation (2007)—which evokes the days of projector beams cutting through the smoke-filled cinemas—the exhibition also includes some two-dimensional works, mainly photographs but also including Albrecht Durer’s famous engraving Melancholia I (1514), which contrasts a geometric solid with a morose angel in what is possibly some arcane allegory.

This suggests that one area in which the exhibition could have done more would have been an exploration of the geometric elements in the symbolism of Freemasonic, cabalistic, and Neo-Pythagorean societies. Arthur Koestler’s 1959 book The Sleepwalkers demonstrated how such mystical concerns related to scientific breakthroughs in earlier centuries, but the intellectual dimension of this exhibition seems superficial by comparison.

Some attempt to compensate for this shortcoming is made by including a Zen-related theme, with circle paintings by the monk Sengai, ink-wash paintings by Sesshū, and some wooden sculptures by the itinerant 17th-century artist Enku.

Until 5th July. 6-10-1 Roppongi, Tokyo. Tel: 03-5777-8600. www.mori.art.museum