August 13, 2009

The Other Expatriates

Joseph Hincks learns the pleasures of exile from members of Tokyo's lesser-known foreign communities

By Metropolis

Photo by Benjamin Parks

Tuong Soi (31, Nha Trang, Vietnam)

“I sold my laptop on Khao-san,” Tuong says, “I got about $300 for it, and I used that money to get to Cambodia.”

“Cambodia?” I reply, “Siam Reap?”

“No, but I met three beautiful Swedish girls on the bus to Poipet, man.” (Tuong says “man” like everyone else, but sometimes throws in the more archaic “boy,” as if caught somewhere between the two.) “They were headed that way and I almost followed them, but I wanted to check out Phnom Penh.”

“Yeah? How was Phnom Penh?” I ask. “I’ve heard a lot about it.”

And it was true, I had. Travelers have been name-dropping the city ever since Lester Bangs’ Psychotic Reactions. But the heavy consonant clusters rolled easily off Tuong’s tongue.

“It’s the same as Vietnam, you know, many poor people,” he replies. “I couldn’t sell many paintings so I had to move on.”

Tuong has been selling Japanese landscapes on Tokyo sidewalks on and off for the past three years. Today he is distracted, helping a local kid set up a fortunetelling stall outside Meiji-Jingumae station. I watch the pair assemble the boy’s personal effects: a collapsible wooden table, a red lantern. “He’s my brother,” Tuong says to me over his shoulder, by way of explanation.

During our interview, I am soon to be introduced to more members of Tuong’s surrogate family: his wild white-haired Japanese “father,” three other “brothers” from three other continents, and a girl from LA he met earlier in the afternoon. “It’s easy to make foreign friends here,” he says with a shrug.

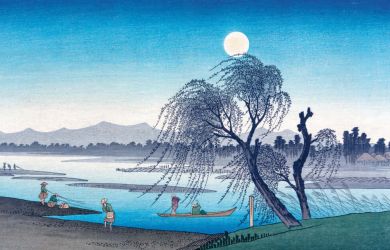

Tuong’s oil paintings are mostly of classical Japanese scenery, but a few Vietnamese landscapes, dotted with thatched housing and humpbacked cows, are discernable among the procession of cherry blossoms. I ask him whether people are interested in his depictions of Vietnam.

“Sure,” he says absently, “Many people see it’s beautiful and they buy. They don’t care, Vietnamese or Japanese.”

On a good day, with an abundance of tourists, Tuong can earn over ¥15,000—minus materials and convenience-store meals—but when it rains, the cost of a night’s accommodation in an internet café must be subtracted from more meagre earnings. He recalls one fortuitous day he earned ¥140,000 from a pair of sightseers. “I spend, spend, spend—beer for everyone, you know, party… and gone. Now I am careful.”

Recently, Tuong found a more stable source of income working in a nearby restaurant. “The owner, he liked me, he’d been to Vietnam one time. I asked, ‘If you don’t mind, can you give me job?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, no problem.’ And I work every day last week. You know, like a kitchen help.”

“What about painting?” I ask.

“Now I’m a little bit retired.” he says. “Now I have a job so… art is only a hobby, man. Because you can’t make money with art. When [the artist is] famous, he’s rich, but when he’s normal, he just paints, and life is there, so… I’m not hopeful about my art.”

It’s gotten pretty dark, and I can tell Tuong is itching to get going. “Look at this,” he says, pulling up his sleeve to show me a crudely rendered tattoo of a green and blue wave, the fresh ink standing up in relief against his skin. It complements the two he already has from Vietnam and Thailand. The designs supposedly ward off harm, encouraging the support of others and bestowing the wearer with good fortune.

“Do they work?”

Tuong smiles serenely at me from under the brim of his hat. “For sure, but without love we cannot go far,” he says. Then, tossing the holdall containing his paintings over one shoulder, he gives me a nod before heading off into the night.