September 11, 2015

War and Postwar

Izu Photo Museum reflects on images from the battlefield

Summer is definitely a good time to get away from Tokyo’s sultry urban heat. The only problem is that, after a few days lounging on a sun-kissed beach or shacked up in the mountains, one starts to miss the rich cultural attractions of the city. Luckily, Japan also has a fair number of art venues dotting its remoter regions, like the Izu Photo Museum in rural Shizuoka, a place definitely worth a visit for those who venture down that way.

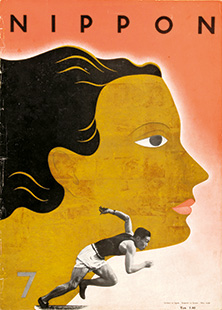

(Cover design: Takashi Kono; photo: Yonosuke Natori), JCII collection

Summer is also the time when the Japanese remember their dead and their tragic World War II experience. So to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, the museum is hosting “War and Postwar: the Prism of the Times”—a special exhibition focusing on the photojournalism of the war and early postwar periods.

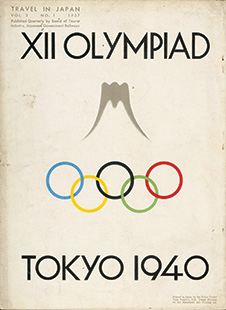

In the run-up to WWII, Japan was keenly aware of its image abroad, and sought to present itself as an assertive and forward-looking nation, with upbeat PR images in a number of government-supported photo journals and magazines, such as Nippon and Travel in Japan, that were intended to show the “best face” of the Japanese empire abroad. The first part of the exhibition focuses on this.

With a surprisingly modern style, lensmen like Yonosuke Natori, who had studied in Germany; Ihei Kimura; and Ken Domon, who went on to enjoy considerable postwar fame, captured images that not only played up the romantic clichés of old Japan, but also emphasized elements of progress. Their shots include pictures of healthy schoolgirls and happy workers, while elsewhere maintaining the myth that Japan was paternalistically looking after the interests of its colonies and client states like Korea.

The tone of this part of the exhibition is reminiscent of Bernardo Bertolucci’s film The Last Emperor, which was set in Japan’s Manchurian puppet state of the 1930s. Cheerful images of Japanese sportsmen and soldiers are juxtaposed with collages celebrating the “diversity” of the empire. Of course, Japan was not the only authoritarian state pretending to be a progressive multicultural one in those days.

The essentially hollow and pompous tone of these images rises to a much shriller note as the Pacific War gets underway in earnest. Morale-raising pictures of Japanese soldiers training—often with traditional weapons to strengthen the “samurai spirit”—or enjoying some leisure time predominate. Some of the photos show surprisingly innocent and boyish faces, and it’s a shock to remind yourself that you are looking at the faces of young men who, history tells us, perpetrated and suffered horrifying acts of violence.

Images from the homefront show crude makeshift attempts to resist American bombing raids, lines of women using buckets to put out fires, for example. Hardly inspiring propaganda!

After the war, those photographers who’d been working for the Imperial government lost their jobs, but many of them found new work producing bilingual publications for the occupying army, and taking photographs that would appear in foreign magazines like Life, presenting a friendlier image of a country that was being shaped for its key role in America’s Cold War alliance.

As well as a master class in photography, this exhibition is an interesting reflection on the Orwellian tendency all regimes have to present a favorable image of themselves, whatever the circumstances.

Izu Photo Museum, through Jan 31. http://www.izuphoto-museum.jp/e/