Japanese bakeries are havens of fusion, a showcase for the adoption and adaption of foreign food in this island nation.

Take, for example, shoku-pan (plain bread). Though wholly Western, and first sold commercially by an English baker in Yokohama, what constitutes a sandwich in modern-day Japan — potato salad, tonkatsu (deep-fried pork cutlet), strawberries and whipped cream — is definitively Japanese.

Sandwiches are but one example in Japan of the successful remixing of bread into new realms of tastiness. And as statistics show, bread is now king. In the past 50 years the consumption of rice has halved, with bread finally outselling rice in 2013 — something it has done ever since.

Indeed, bread in its many guises forms the basis to dozens of foodstuffs now heavily associated with Japan, from perfectly formed sandos that winged their way to Brooklyn and beyond to the union of curry and deep-fried bread in karē-pan (curry bread).

Anpan is possibly the oldest of such fusions. Consisting of anko (sweet red bean paste) encased within a ball of bread dough, this creation has been going strong since the late 19th century. It was first created by Yasubei Kimura, a former samurai turned baker who founded his own bakery, Bun’eido, in 1871. This soon relocated to Ginza and was renamed Kimura-ya.

Loaves were the original product on offer at Kimura-ya. But Yasubei’s son, Eisaburo, apparently wondering how best to boost the appeal of unfamiliar bread to Japanese people, settled on recreating manjū (sweet dumplings), which are often filled with anko, but in bread form. And with bakers yeast hard to come by, he utilized sakedane (yeast used to make sake) for this new product. Anpan was born.

One of several toppings – others including sesame and poppy seeds – sakura no shiodzuke (salt pickled cherry blossom petals), had its first trial run in a big way on April 4, 1875, when noted swordsman and samurai Yamaoka Tesshu presented one to Emperor Meiji during the latter’s visit to the Mito clan’s Edo residence for hanami (cherry blossom viewing). It was a hit, sealing the deal for the popularity of anpan; though not exactly a national holiday, April 4 is still held to be Anpan Day in Japan.

Whether or not this high-brow showcasing of Kimura-ya’s product was a sales pitch, who can say, but the bakery earned itself a goyо̄tashi for its goods — the equivalent of a Royal Warrant of Appointment in the UK (though Japan’s goyо̄tashi system was abolished in 1954).

At the time, the Japanese diet was under the microscope particularly in the military world. To combat cases of potentially fatal beriberi (caused by a lack of vitamin B1), in 1884 the Imperial Japanese Navy experimented with a Western diet aboard its ships, a medley of barley rice, biscuits, condensed milk and meat. The Imperial Japanese Army lagged behind due to a difference in opinion on the causes of beriberi, but implemented a seven parts white rice, three parts wheat-based diet in 1913.

On the advent Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), Kimura-ya’s anpan was sent along with soldiers from all over Japan, switching its fortunes from Ginza curio to the new sweet treat known nationwide. In the meantime a taste for bread had emerged: by 1883 there were 113 bakeries operating in Tokyo.

Buoyed by this new fame, and the city’s newfound predilection for bread, Kimura-ya boomed. In 1897 the Ginza store was selling around 100,000 anpan per day. In 1900, jamu-pan (jam-filled bread) followed the success of its azuki bean-filled predecessor, inspired by German confectionary brought home by Japanese soldiers who studied there following Prussia’s victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). Originally filled with apricot jam instead of strawberry (that would come later), it was another hit for Kimura-ya.

Fame of anpan spread. It reached Hokkaido, where confectioner Onuma Jinzaburo was selling confectionary to the 25th Army Infantry Regiment stationed at the town of Tsukisamu, just outside Sapporo. Onuma had heard about Kimura-ya’s anpan, and in 1874 devised his own version. Dubbed Tsukisamu anpan, these are less like the round, doughy anpan of Kimura-ya, more like a bready geppei, better known as mooncakes. These were supplied to the 25th Regiment and local workers in 1911 during the construction of a road from Tsukisamu to Hiragishi — National Route 453 officially, it was nicknamed Anpan Road owing to the sweet fuel that kept workers going. One of several suppliers in the area who were instructed in the creation of the new anpan was Yosaburo Honma, founder in 1906 of a confectioners that bears his name today: Honma.

The early spread of anpan says much of its original connection to the perceived nutritional value of bread, or Western food in general. Its status not only as a confectionary but as sustenance for soldiers is telling. In its synthesis of anko, a traditional filling dating back to the Kamakura period (1185–1333) or earlier, and bread, a Western introduction but leavened with sake yeast, anpan holds up a symbol of a Japan’s rapid industrialization at the close of the 19th century.

Anpan were evidently embedded deeply within Japanese food culture by the time World War II rolled around. Towards its close, with logistics in disarray and food in short supply, a non-commissioned officer by the name Takashi Yanase, who was stationed in China and often on the verge of starvation, dreamt of eating anpan again. On his return to Japan, Yanase worked as an editor at the Kochi Shimbun before moving to Tokyo, deploying his services as a graphic designer for Mitsukoshi while pursuing manga on the side. Eventually, in 1973, he created a character inspired (at least partly) by his WWII experiences: Anpanman.

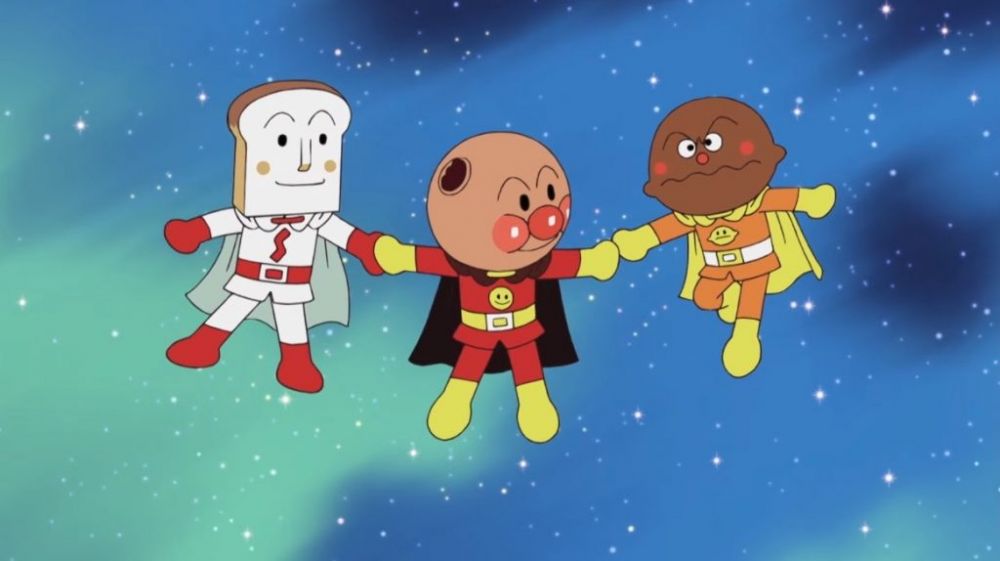

In Anpanman, the title character has an anpan for a head. He flies around looking for people in trouble. Sometimes they’re just very hungry — something Anpanman solves by giving a portion of his head for them to eat. With many other characters (1,738 in the animated series, a world record) including Shokupanman, whose head is a slice of white bread, and Karepanman, who has a karē-pan for a head, the use of anpan in particular for the titular main character hints at its singular symbolism and heritage. It’s the oldest of Japan’s fusion bakery goods, a melding of West and East raised to superhero stature.

While Anpanman remains omnipresent, adorning lunchboxes, children’s magazines and enticing them to eat well at family restaurants, you’ll have to travel if you want to meet him in person (kind of). In Yokohama you’ll find the Anpanman Children’s Museum, one of five in Japan. Here you can purchase his disembodied head from Jam Oji-san’s Workshop, an onsite bakery. It’s anpan, but adorned with Anpanman’s meekly smiling visage (¥390).

For a taste of the original, head to Ginza and pay a visit to Kimura-ya. Various anpan (from ¥200) can be had here, from keshi (with sesame seed topping) to the smooth sweetness of uguisu (green bean paste) and shiro (white bean paste). Further west, the uber-cheap Komine Bakery lies at the end of Tokyo’s longest covered shо̄tengai (shopping arcade) at Musashi-koyama Station, Shinagawa Ward. Komine’s anpan can be sampled from the rather inviting price of ¥110.

Over in Asakusa old-school bakeries bristle the streets, but Andesu Matoba is famed for its anpan. Most popular is their koshi (fine red bean paste; ¥190), as opposed to tsubu (coarse), but it’s a matter of preference. For something extra special, however, it’s worth paying a visit to Meika Seven, a stone’s throw from Ojima Station, Koto Ward. Located along the Sun Road shо̄tengai, its signature usukawa (thin-skinned) anpan, stuffed to bursting with the refined sweetness of bean paste, is a dream for adorers of anko.