December 20, 2022

Based in Japan: MIYACHI

Hip-hop artist and Youtuber bridging cultures and scenes

The “reporter” with a microphone in one hand and a can of chu hai in the other is just one of MIYACHI’s personas. Often out in the streets of Tokyo interviewing drunken members of the public for his YouTube channel Konbini Confessions, he nonchalantly poses questions on everything from your biggest regrets in life to your favorite vegetable. The result is three to eight-minute videos of Q&A inebriated truth-telling chaos that have amassed millions of views across the world.

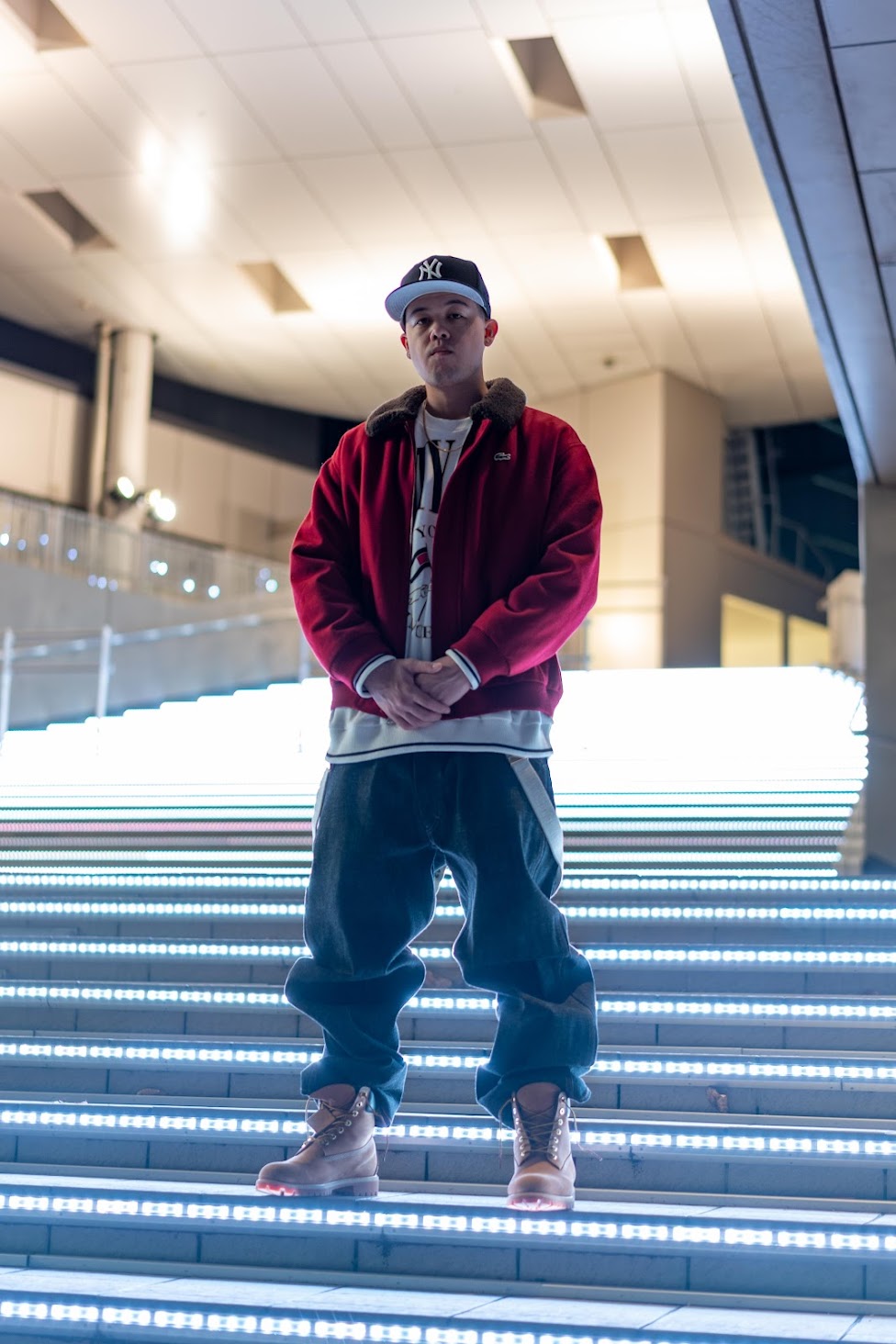

When he swaps the beige slacks and black tie for Timberlands and a Yankees snapback, however, MIYACHI is ready to focus on his career as an artist. Following on from his debut album WAKARIMASEN in 2019, the New-York native has recently been using his life in Japan as the foundation for both his new single “MAINICHI II” and his new album, Crows. While the artist might be more accustomed to conducting the interviews, the Metropolis editors inverted things at the rooftop skatepark in Odaiba to quiz him on his music.

With the Rainbow Bridge and Tokyo Tower as the backdrop, we and his team huddled in the park’s cafe to hear about his creative journey, how living in Japan has inspired his music and the messages being translated through his lyrics.

What’s your background?

I was born and raised in New York but I came to Japan every year for a few months in the summer, so I had opportunities to make friends and be a part of the school system and the culture. Still, I had culture shock coming here as an adult and navigating my artist career. It’s a whole other ballgame—I understood parts of the culture, but there was a lot that I didn’t truly understand.

How are you using this dual identity as an artist?

I’m trying to form the bridge, you know what I’m saying? My work is naturally going to be in some way from an outsider’s perspective, because that’s naturally what I am. At the same time, I’m learning and being a part of the community here, and growing my career. The word “authentic” depends on the angle you’re looking at. I think it’s really about playing that middle, just being genuine about it and my experience within it.

A lot of U.S. rap lyrics these days flex success or wealth, but based on Konbini Confessions, you seem equally at home hanging outside a konbini with a chu hai and drunk people in Tokyo.

That’s just who I am—I’m not the most bling-bling, money-driven person. But the thing is, hip-hop was, at its essence, a revolution. It was “Fight the Power,” a rejection of the system, the corporations and the norms. It was more about empowering people. The whole get money, rocking designer and showing off ? That’s really more a by-product of how successful hip-hop became, but it’s not really what it originally was. I’m trying to be a genuine bridge. I’m from New York; I feel as though my career and my life have been that of the underdog. That’s true when I’m representing others. I would rather relate more to the common man.

The follow-up single to “MAINICHI I,” “MAINICHI II”, came out in September 2022. What’s the story behind these projects?

In the music videos, I’m playing the character of a Japanese salaryman and they’re following him as he’s kind of losing it. Thematically, I think his experience is relatable for many people, because it’s the same story everywhere: the working-class person who’s fighting to move up or to have the freedom to be able to make their own decision. Even in the YouTube comments, I see people saying that they have similar scenarios in totally different countries. Just to have enough time and money to survive and live happily, that ability to have as much freedom as you can within the structure of that system.

I used what I was observing being in Japan—looking at salarymen on the train, going into these kinds of offices and talking to people, getting to know them. I used all that as the setting for this character and his personality. The video content is quite violent— the office employees rebel by shooting the shachou (company president) and even their colleagues.

As it’s a pretty extreme critique of the work culture here, were you concerned about how it would be received?

I had to put up a disclaimer because we were kind of worried that people were going to interpret it as insensitive. I’ always checking with people to make sure [it’s OK] because, although cancel culture is recent in America, cancel culture over here in Japan is a beast! Especially since I’m not fully born-and-raised here, I need to understand certain parameters—that’s just being smart. If I’m going to talk about something, I want to make sure it’s communicated in a way that’s going to resonate. It’s not necessarily because I’m too afraid to offend somebody or anything like that, but I just want to get the right thing across.

Your latest album, Crows, dropped this December. What’s behind that?

It’s almost entirely in Japanese—about 70 percent. The significance of why it’s called Crows is connecting “MAINICHI” and that way of thinking with living in this new experience of 2022. I kind of started learning about crows as an animal, and realized that they’re extremely intelligent and very adaptable to pretty much an environment. They’re very communicative with each other too—they have things that they do in respect of or in the protection of each other. With this communication, they kind of have the ability to warn each other about the future. I feel as if we need to be like that in this day and age, so that’s why it’s called Crows.

Crows is mostly in Japanese, but how do you work between both languages?

I dropped my debut album WAKARIMASEN in 2019. That was half in Japanese and half in English, but I felt it would be better if I could go project by project and really focus in on the audience that I’m talking to with each language. So this time, I wanted to connect more with my Japanese fan base. I had a chance to get a lot better at Japanese, to express my emotions better, and learn how to be a better MC, a better rapper in Japan. I plan to do English projects in the future, but Crows is a Japanese one. I think the album slaps, so hopefully the language won’t even matter to some people.

In a recent Konbini Confessions video, out of everyone you asked, no one knew any of the huge U.S. rappers. My favorite moment was when you asked a girl if she knew Snoop Dogg and she said “What? Sniff tofu?”

I just like to ask shit that throws people off because it’s mad funny, you know? [Laughs] There wasn’t a deeper agenda, I just knew that they didn’t listen to Snoop Dogg. It’s not just making fun of them though, it’s like a cultural service—American people will watch that and they might be like, “Wow. This culture is really far away from what we consider to be normal.” Sometimes Americans assume that everybody knows what they know. In Japan, they’ve got their whole own world going on. [Laughs]

I honestly think it’s cool that they don’t know Snoop Dogg or Drake. That’s what’s dope about Konbini Confessions—you learn about people and find out stuff that you just wouldn’t expect. And you also find out similarities that you wouldn’t expect. That’s definitely cool.

J-pop and now K-pop dominate the Japanese music charts. What do you think needs to happen for Japanese hip-hop to be more mainstream like it is in the U.S.?

I think eventually it’s going to be the same thing that happened in America, where it’s too popular to be denied by the big companies. The thing is, you have these big J-pop conglomerates that are hogging the billboard chart and the mainstream sound, but I think at a certain point you’re going to have that youth movement, and it’s going to be too big to ignore. That’s exciting. For

me, I also hope to start gaining a fan base in America, but I’ll never have the same opportunity there to break new ground

as I can here. Hip-hop is everywhere in America, but there’s an opportunity in Japan to be a part of breaking down these

doors for the first time.

The East Coast-West Coast hip-hop rivalry was a huge catalyst that fueled the evolution of American hip-hop. Could lacking a sense of rivalry also be holding Japanese rap back?

That’s a good question. I don’t know if it’s holding it back in Japan, but I think that even though it may not be in the lyrics, or in may not be in the energy of the rappers when they’re interacting with each other, it’s still there behind closed doors. There’s still like, “Damn, how did you put out that hit record? I’m trying to one-up that, for sure.” That’s just the natural mentality, but for Japanese people, the competitive or aggressive environment is not really our thing.

I’m from New York, so when I was a kid it was always competitive aggression at school. I definitely want to keep that part of me in there. I want to feel like I’m the best, not because I want to put other artists down, but because I want to work hard in my craft and be able to make the best sounds you know? I want to sit on that hill.