January 31, 2017

Gods, Swamps, and Christianity in Japan

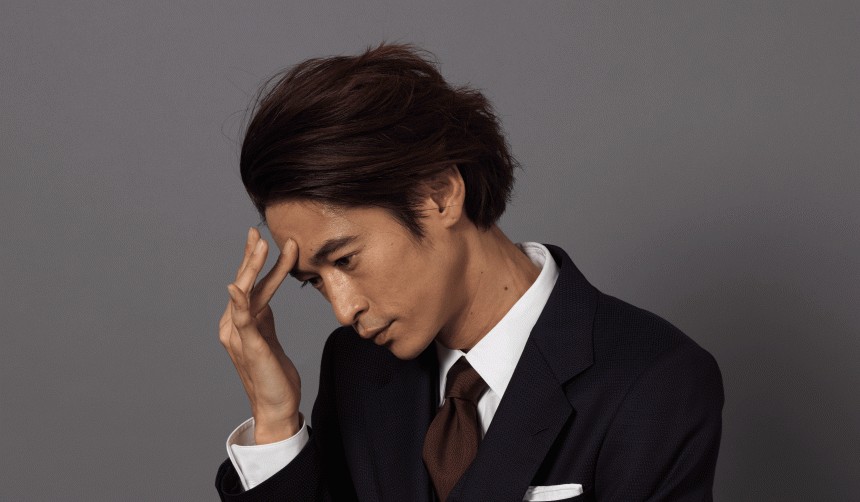

Kubozuka: "SILENCE refers to the silence of God"

Current estimates put the number of Japanese people who identify as Christian at roughly 2,000,000. That may seem like a lot, but in a country of nearly 130 million, that’s less than 1 percent of Japan’s entire population, meaning that when you account for statistical error, Japanese Christians might not actually exist at all. But I’m just being flippant—of course they exist. Hell, one of them even wrote a book about Christianity, which eventually went on to become the basis for one of the most critically acclaimed movies of 2016: Silence.

Silence tells the story of two 17th century Portuguese priests traveling to Japan (then in the midst of resisting brutal European colonialism) to look for their mentor. The film explores complex themes of religion, morality, and how far people are willing to go for their faith; it was adapted (incredibly faithfully) from a novel by Shūsaku Endō, who was partially inspired to write the book after experiencing discrimination due to his Christian faith. On the surface, it doesn’t sound like the kind of story that director Martin Scorsese would be interested in, given his track record of violent movies like Taxi Driver or Goodfellas—movies that more often explored the themes of drugs, crime, guns, and what happens when you mix all three.

But what many people forget is that faith and redemption have always been an integral part of Scorsese’s filmography, like in The Last Temptation of Christ. Yōsuke Kubozuka, one of the stars of Silence, summed it up best when he said:

“In Scorsese’s gangster movies, religion, especially Christianity, always plays an important role. I think the director even said himself that he thought about becoming either a gangster or a priest. And in a way, I think Silence is a movie about that, a kind of internal struggle. That’s why Scorsese was the best man for the job.”

In the movie, Kubozuka plays Kichijiro, a Japanese convert to Christianity who embodies the story’s central theme of struggling with one’s faith. This is apparent especially during the fumi-e scenes. Fumi-e were crude depictions of Jesus or the Holy Mary, which people were ordered to step on to prove that they weren’t Christians. Throughout the movie, Kichijiro is shown repeatedly to step on the fumi-e in front of government officials, despite never truly rejecting his Christian faith.

“Shūsaku Endō said ‘I am Kichijiro,’” Kubozuka explains. “In other words, the people of this world, everyone who is alive now or then, Kichijiro is meant to be like them. He is meant to be the everyman. When I went to America and I asked people if they’d have stepped on the fumi-e, many people said that they would to save their lives.”

It’s easy to see why Christians might fail to resist, given that the punishment for practicing Christianity in Japan during the 1600s was the stuff of nightmares. In Silence, Christians are punished through the practice of anazuri: they are suspended over a pit and left to slowly bleed out over the course of days, sometimes weeks. Not wanting to experience such horrors, even at the cost of committing blasphemy, is perfectly understandable and human.

However, it must be noted that, unlike Kichijiro, many Japanese Christians have laid down their lives for their faith. This raises the question: if the country’s citizens were willing to become martyrs for Jesus, why hasn’t Christianity truly caught on in Japan?

The book and movie tell us that it’s because “Japan is a swamp,” a place where nothing foreign could ever sprout roots and thrive, especially Christianity. On the one hand, there is definitely some truth to that analogy. Religion in Japan has always been less metaphysical than in the West. The country’s two dominant religions, Buddhism and Shinto, differ from Christianity in that they put more emphasis on people. In fact, in Shinto, it’s entirely possible for humans to become gods (kami). The Shinto god of learning, for example, is a real historical figure named Sugawara no Michizane.

This unique way of thinking is shown to even influence the way Japanese Christians approach their new religion. In Scorsese’s Silence there is a scene, given substantially more attention than in the book, where the Portuguese priests notice that Japanese Christians are more interested in physical, material symbols of their new faith, such as crosses or rosary beads, rather than the faith’s spiritual aspects. One might conclude that the reason why Christianity never thrived in Japan is because the innate real-world-centric mentality of Japanese people is just incompatible with the idea of an incorporeal, omnipotent and omnipresent Deus.

On the other hand, “I think that Christianity may definitely be right for some Japanese people; it might be the road to their salvation,” Kubozuka says. “’Silence’ refers to the silence of God, meaning that everyone has to look inside their heart and make sense of it themselves, and this can take many different forms. It can be Christianity, Buddhism, or Islam. It doesn’t matter how you call it. If you find an answer that works for you, then that’s what you should believe in.”

The “swamp” analogy also obscures the geopolitical dimension of this encounter. Missionary work in the 16th and 17th centuries was frequently intertwined with violent European colonialism, and the Portuguese were enslaving Japanese people. For the Tokugawa government, restricting Christianity was as much about protecting the country from foreign intervention as it was about religious incompatibilities. In that sense, Japan’s resistance played a role in preserving its sovereignty.

Silence does not remain completely impartial in this debate as it does go on to uncover the cruelty underneath the polemic of 17th century Japanese officials and their swamp analogy. This is most notable during the scene when (possible spoiler for the movie) a priest was forced to renounce his Christian faith and write the Gengiroku, a treaty pointing out all the supposed mistakes and failings of the Christian faith. This is an actual historical document written by a Jesuit priest who became the basis for one of the characters in the movie. The only purpose of forcing the priest to write the book was to humiliate a beaten foe, which casts a shadow of doubt on the Japanese officials’ allegedly philosophical and political objections to Christianity.

But pointing out the insincerity of government inquisitors isn’t really the point that Endō or Scorsese were trying to make. If their story had a point, it’s probably closest to what Kubozuka said: “To me, religion is all about finding happiness…but ultimately it all comes from within you. It’s more like your religion is a representation of who you are.” Because when we’re confronted by the silence of God, the only meaning we can find within it is something that we already believe—that God wants us to have faith, that God is punishing us by not answering our prayers, or that he simply isn’t there.

One of Silence’s Portuguese priests spends a lot of time pondering this, trying to understand who he really is as a person. In the end, Silence asks questions about faith to which it doesn’t have the answers, forcing us to look within ourselves to find them.