March 20, 2009

Head Case

In his new documentary, director Kazuhiro Soda explores the taboo subject of mental illness

By Metropolis

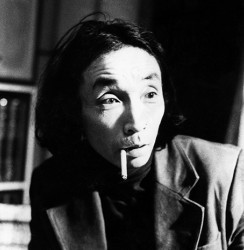

The stars of Mental are the doctors and patients, and much of the film’s power results from its strong cast. One patient is a former high-flying businessman who wound up burning out. Another is a woman who developed an eating disorder after being told that her legs were fat. Yet another is a manic depressive with dreams of starting a farm in the countryside. And then there’s a character named Sugano, who one moment is doing an impersonation of a steam train with a lit cigarette up each nostril, the next reciting poetry.

The more Soda filmed, the more he came to respect the patients and realize that their experiences were not all negative.

“Of course, they are suffering and they want to get rid of their illness,” he says, “but at the same time, for example in the case of Sugano-san, he couldn’t have written those poems if he hadn’t experienced illness. In a sense, his illness makes him a more interesting, attractive person. Sometimes being ill can be a strength, not a weakness.”

Mental was filmed by both Soda and his wife, Kiyoko Kashiwagi. As an experienced director accustomed to being behind the camera, Soda was able to maintain a distance from his subject matter. For Kashiwagi, this was not so easy. After spending so much time at the clinic with the patients, she began to question her own mental state. Eventually, she herself made an appointment to see Yamamoto.

“I felt really sorry for her as a husband,” Soda recalls. “But at the same time, as a filmmaker, I thought, ‘Mmm, this is interesting!’ Actually, she refused to allow me to film her consultation, but the point is, I think the roles of healthy/unhealthy are very ambiguous, and it’s very easy to cross between the two.”

Given Mental’s controversial subject matter, it’s difficult to predict how audiences will react when it’s released here in Japan. Soda realizes that he risks being accused of exploiting the patients, but his biggest fear is that controversy might negatively affect the lives of the people depicted. To make sure everyone involved in the film knew how they were being portrayed, the director organized a private screening for patients and staff. He confesses that despite gaining the patients’ permission to be filmed, he was worried about their reaction. At first, it seemed his fears might be realized.

“As soon as we announced the screening, some of the patients said they wouldn’t see the film. I was most worried about one patient in particular, whose baby had died. She hadn’t told many people about that, but she had confessed to me on camera about her role in the baby’s death, and I kept this confession in the finished version. I heard before the screening that she’d said that she wasn’t coming, so I was worried about what might happen if she heard things about the film from other people. I knew that she’d tried to kill herself six or seven times the previous year.”

The patient arrived at the screening after her scene had been shown, but in a discussion afterwards, she asked the director if he had included “that” scene.

“I told her that I had. At first, she was very disappointed and angry. She said, ‘So everybody knows about that… now I won’t be able to live.’

“I didn’t know what to say, but then another patient raised her hand and said, ‘Well, it was shocking to learn what happened, but I am glad I now know your suffering. I didn’t know you as a whole person before and now I do, and I’m not changing my mind about you. I’m a mother, and I know how hard it is to raise a kid.’ I think it was the first time that people had listened to her story, and I think she was surprised that anybody could possibly sympathize with her.”

With an increasing media focus on violent crime, often committed by people seen as mentally ill, Soda’s film offers a different view.

“In the case of the woman I talked about, in the news she would just be portrayed as an evil mother—it’s always black and white,” he says. “But if you listen to the stories of some of the people involved in these things, it’s not that simple… Demonizing people doesn’t solve anything. In a sense, I want to provide an antidote to that kind of attitude. It wasn’t my purpose when I started filming, but I am hoping this film will show that these people are human beings and they are vulnerable. We are all vulnerable and need support. If somebody was there to listen to these people, maybe some of the crimes wouldn’t happen.”

In a sad footnote, three of the patients who appear in the film have killed themselves since it was made.

Mental has won the Best Documentary Award at both the Dubai and Pusan film festivals, and when it debuts in Tokyo, selected screenings will be with English subtitles. Whatever the reaction, it seems likely that the director will achieve at least one of his aims: bringing the topic of mental illness out into the open, at least for a little while.

For more information about Mental, see www.laboratoryx.us/mental.