March 15, 2022

Tokyo Neighborhood Guide: Kasuga

Heartlands: Salt Jizo, Konyakku Enma and Tokugawa connections

Linger long enough at the top of one of its many hills and you might be able to imagine what life was like in Kasuga 400 years ago. Without the envelopment of highrise buildings and shrill soundtrack of sirens in the distance, this formerly rural portion of Tokyo — outside of the walls of Edo Castle — would have had views that stretched for miles.

Located in the south of Bunkyo Ward, within walking distance of Ueno Park and Tokyo Station, Kasuga is conveniently connected to the rest of the city by the Oedo and Toei Subway lines. The long, thin slip of town stretches out alongside Kasuga-dori under the watchful eye of the rollercoasters at Tokyo Dome. It’s the kind of an area where nobody seems like a local, office workers rush by on their way to work and visitors, hands-on phones, look for the best places to eat.

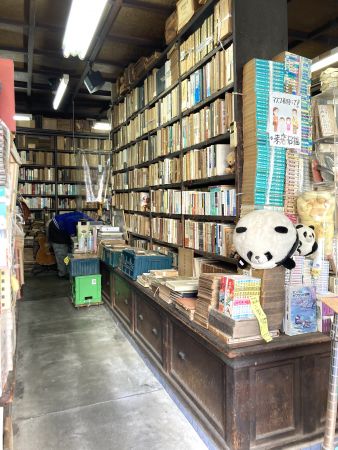

Despite the onslaught of big business and contemporary construction, Kasuga maintains a hushed, old-fashioned character. Showa-era (1926-89) shops are still open for business, although sadly — like the newly closed Eagle Bunkyo Bakery that opened in 1933 — are slowly being replaced one by one. Neighborhood pavement gardens color the shotengai (shopping street), each household and shop tending to its individual portion of the street, bringing life to the concrete.

Like many other areas of central Tokyo, clues to Kasuga’s past aren’t far from the surface. It was here along its slopes that samurai abodes, shrines and temples were built.

The district is named after noblewoman and politician Saito Fuku. In 1626 after spending many years working closely with the Imperial family as a wet nurse for the third Tokugawa shōgun Iemitsu (1604-1651), Saitō was given a promotion and honored with the title of Lady Kasuga. Her role was to oversee the Ōoku, the women’s quarters of Edo Castle where the shogun’s wife, family and concubines lived. A few years later in 1630, Saitō asked Iemsitu for some land and she was given the area that is now known as Kasuga.

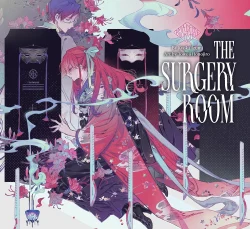

Today, leaving Kasuga station, the retro-covered Enma-dori shopping street has long since replaced the fields and stately homes. The sloping road hosts ramshackle bookshops that feel a spillover from Kanda. It’s not long before Genkakuji Temple appears, its entrance a little underwhelming at first, but a strange tale brings worshippers here.

Built in 1624, the temple enshrines a wooden statue of Enma — the Buddhist deity of the underworld — believed to date back to the Kamakura Period (1192-1333). Iemitsu himself would worship at the temple during the Edo period, but sadly it was damaged by fire multiple times over the years including a large one in 1848. The temple was reconstructed in the Meiji era (1868-1912) and made it through both the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and World War II unscathed. Thankfully the wooden Enma, known affectionately as Konyakku Enma, also survived.

The story goes that during the Horeki era (1751-64), an elderly woman suffering from an eye disease prayed every day to the wooden statue for a cure. It turned out that the cure was giving up her favorite food, konnyaku (gelatinous cake made from devil’s tongue). Following this prognosis, Enma gave the woman his right eye, and the disease was healed. To offer her thanks, she continued to offer konnyaku to Enma. To this day, the gray, speckled cake is still piled up at the foot of the wooden statue by worshipers, especially those with eye problems. Piles of the gelatinous foodstuff now surround a picture of the statue, understandably too precious to be in plain view. The statue’s right eye mysteriously remains a cloudy yellow color.

Another intriguing site in the temple is shio-jizo-son — two statues of jizo (guardian deity of children and travelers) completely caked in salt. Like the healing Enma, legend has it that pouring salt onto a specific part of the statues will help cure your corresponding ailments.

Leaving the temple behind and heading up the sloping roads a little, there’s more history to stumble upon — namely Tsuki-sando Zenkoji temple in the middle of Zenkoji-zaka hill. Thought to date to 1602, the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu’s mother Odai no Kata is enshrined here. Enter through the beautifully worn wooden gates into the quiet temple grounds. In spring, blossom elegantly frames the building; there’s also a monument to haiku master Matsuo Basho here.

A little further towards the top of the hill is Takuzosu Inari-jinja. This large Shinto shrine is carefully maintained and even has its own instagram page, a hint to its photographic credentials. Don’t rush past this tranquil shine: walking alongside the right of the main building leads along a small path and down into a small secluded grove beset with a charming set of red torii (gates) and numerous crumbling shrines to Inari, the fox god. Standing here under the calm rustle of the trees is one of those times that it’s hard to believe you’re in the middle of one of the biggest cities in the world. Walk a little further to Zenkoji-zaka Muku-no-ki — a 400-year-old tree that survived the air raid in May 1945.

Like temples and shrines, thankfully good food is never too far away in Tokyo. On a sunny afternoon, the nearby Aoi Napoli provides an escapist lunch break. Sizable servings of pizza and pasta are served up trattoria-style on a plant-fringed second-floor patio. The reasonable lunch deal (from ¥1,200) makes it more affordable. For something a little more retro and easy on the wallet, Coffee Ann provides — as long as you don’t mind waiting in line for 10 minutes. Opening in 2005, the cozy kissaten (old-school coffee house) is run by a brisk but welcoming team of aproned staff, who will swiftly seat you and take your order.

Lunch sets here change depending on the day of the week. On Saturdays, the choice is freshly made croque madame (ask for it minus the ham for veggie) or tuna mayo teamed with avocado, served alongside a small side salad and a cup of steaming coffee, all for a mere ¥840. There are even wi-fi and table-side plug sockets for charging devices.

More post-lunch temple searching and backstreet exploring can be done in Kasuga. It’s almost impossible not to pass historic signboard sites as you walk around, and even the backstreet roji (tiny alleyways) portion of the neighborhood offers an insight into how much of Tokyo used to live. Here small communities are still huddled around outdoor water pumps, front doors almost opening onto their neighbors.

Further afield, the sculpted landscape of Koishikawa Korakuen adds to the historic attractions and, of course, there’s always a rollercoaster ride or arcade game to play at Tokyo Dome. But away from the big-hitter destinations, looking past the tower blocks and main thoroughfares, and simply walking through this historically dense neighborhood, offers a peek into the city’s heritage before the sprawl.