April 26, 2012

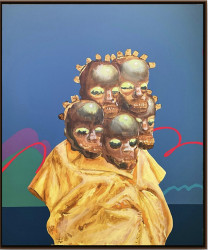

Lee Bul

The Mori shows the feminism and femininity of the avant-garde Korean artist

By Metropolis

Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on April 2012

Lee Bul seems to be famous for all the wrong reasons. The major Korean contemporary artist, who has a retrospective at the Mori Art Museum, had her first big break in 1997 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, when an artwork she was exhibiting, containing dead fish, literally started stinking and forced the exhibition to be shut down.

The controversy this caused led her to get noticed by the wider art world. Yes, once again, as with Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, Chris Ofili’s elephant dung paintings, or Damian Hirst’s pickled animals, a contemporary artist gained fame by doing something repulsive to normal people.

Lee is also considered a major contemporary artist because her work can be loaded with heavily politicized interpretations, although, to be fair, these are usually the work of overactive curators. The main way in which her art is politicized is with a feminist narrative, but the fact that she was reared by left-wing parents at a time when South Korea was less than fully democratic also crops up in explanations of her art.

One suspects that some of her less successful artworks, like Aubade (2007), a pointless piece of scaffolding that genuflects in the general direction of the Soviet Constructivist movement, are partly driven by the artist’s attempts to live up to the more overblown rationalization of her work. These occasionally try to invoke the totalitarianisms of the 20th century, presumably because Lee’s from the one country that is still stuck in the Cold War.

But despite these negatives, there is still something attractive about much of her art. In her 1999 video installation, Amateurs, the viewpoint gets tossed around like a ball between a group of Korean high school girls, with the film slowed down at crucial moments to give us little moments of voyeurism: a bit pervy but definitely enjoyable.

Despite her feminist agenda, it’s artworks like this, characterized by playful femininity, that are the most effective. Her earliest works, outlandish soft-sculpture body suits, which attracted attention and made movement difficult, clearly fit into this category.

Of course, the official, feminist, Germaine-Greer-approved explanation is that these suits represent the impediment of fashion, from the foot-binding of Manchu China to the high heels of today, and the enslavement and objectification of women, but if this were all they are, they would be terribly boring.

Instead, the video installations that illustrate this part of the exhibition, like Cravings (1989), show the artist moving around awkwardly, enjoying the shock of onlookers and being the centre of attention. The suits, which are hung from the ceiling, are impressive objects in their own right and suggest that women, as the weaker sex, have always found numerous ways to compensate in the supposed battle of the sexes.

A similar bifurcated narrative can be constructed for her many sculptural works, which evoke the human body, often in truncated or android form. While those keen to press the hoary old feminist agenda can see her one-legged Cyborgs (1998) as yet another expression of evil male-chauvinist society hamstringing women, others might see a delight in fetishistic power. Indeed, some of the pieces, like the glitzy tendril-spewing sculpture Apparition (2001) had me thinking of Lady Gaga’s more extravagant costumes.

One of the noticeable features of the exhibition is that it includes a full-scale recreation of her atelier. Here we can see how she works through her ideas and develops them in various directions. What I noticed is that although her studio is very neat and well organized, the ideas themselves seemed rather messy and confused. This goes a long way to explaining Lee Lee’s art.

“Lee Bul: From Me, Belongs to You Only,” Mori Art Museum, until May 27 (listing).