Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on October 2013

One of the most delightful museums to visit in Tokyo is the Idemitsu Museum of Arts. It is set several floors up in a building that overlooks the Emperor’s Palace and from the viewing room, you can sit back in a comfortable armchair with a warm, free cup of Japanese tea in your hand and look out over the green moat that surrounds the royal residence.

Although funded by an oil company, the museum is dedicated to traditional Japanese art, with the latest exhibition being “Sengai and the World of Zen.” This exhibit’s works—it’s probably best not to call them “artworks”—are by a Zen Buddhist monk who lived from 1750 to 1837. Typically, these are quickly drawn, usually chaotic-looking ink paintings, often with accompanying calligraphy.

According to the exhibition’s curator, Hirokazu Yatsunami, there is an interesting story—which may or may not be true—that Sengai was actually a highly accomplished artist until someone reminded him of Sesshu Toyo, the most famous master of ink painting who lived in the 15th century. Sesshu had also been a Zen master, though people had forgotten this because of his great artistic skill and merely saw him as an artist. From that moment on, Sengai decided not to repeat Sesshu’s mistake and started to paint in a way that would always remind people he was a Zen master first and foremost—and an artist a very distant second.

There may well be something to this story because there are pieces like Daruma (1827) and The Willow (undated), where a sureness of touch and an instinctive compositional nuance shines through despite his slapdash methods.

Nowadays, people have the sometimes-irritating habit of asking what a painting is about or what the artist’s message is. For Sengai this was the key, and art that got in the way of the message by being too impressive or awe-inspiring was bad art. Instead, his paintings aimed at disarming the viewer with humor and a sense of effortlessness.

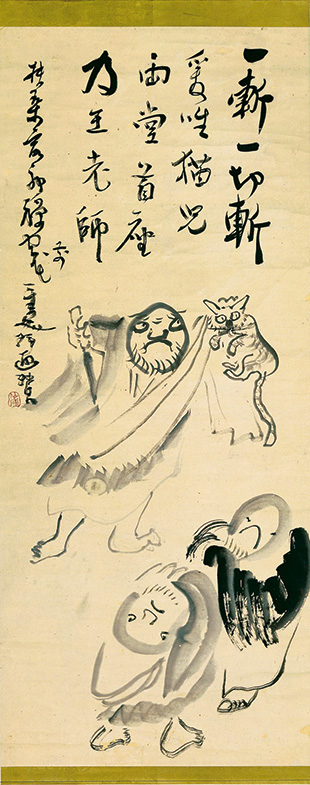

He also clearly wanted to raise questions in people’s minds and make them think. This is certainly the case with one of the most interesting paintings, Nanquan and the Cat (undated).

This is a depiction of a famous story about the Chinese Zen master Nanquan Puyuan (748-834). One day some of his monks were quarrelling over a pet cat. Displeased that discord had thus been introduced into his monastery, Nanquan immediately picked up the poor creature and dispatched it with a knife, as shown in Sengai’s illustration.

This story was accepted as a classic demonstration of the wisdom of Nanquan in nipping things in the bud, but according to Yatsunami, Sengai was unique because he was the first famous Japanese Zen master to start questioning such parables. This can be seen in the message written next to the picture, which raises the question of whether it is only the cat that should die. Was there perhaps not a less violent way to solve this problem?

Sengai’s work continually comments on Buddhism in this way, without ever getting in the way of its subject or eclipsing it with showy artistry, making him the quintessential Buddhist artist.

The show also includes items and utensils used by Sengai as well as some calligraphy by Ikkyu (1394–1481), another famous and eccentric Japanese Zen Buddhist monk.