By Paul McInnes

Spirit in Tokyo

Filmmaker Sam Tibi captures the calmness and serenity of the capital

July 26, 2019

Metropolis talked to filmmaker and film school graduate Sam Tibi about his new, absorbing short film Spirit in Tokyo. Tibi, raised in France and currently living in London, describes his mesmerizing movie as a “20-minute meditative exploration of Japan’s busy capital.”

Metropolis: You really captured the solitude of Tokyo in your film. Was it difficult to find quietness in the biggest and most frenetic city in the world?

Sam Tibi: It wasn’t. It’s interesting that you associate “quietness” with “loneliness”; there is indeed a quiet quality to loneliness. But loneliness can be found in the busiest places. In a crowd, a tube, a shopping mall or one of those crazy gaming centers. It’s all relative to the framed subject, and where his/her attention is directed. In that sense, I wasn’t necessarily looking for quiet places, as those “quiet moments” can be found anywhere, especially in the loudest places.

M: How did the film come about? How much preparation did you do and how long did you spend in Tokyo?

ST: “Make a film about Tokyo and win £15K” — this was the online advert a friend and I came across. It explained that one of the largest film festivals in Asia had created a new entry category named “Cinematic Tokyo,” accepting any film made in or about Tokyo, with a £15K prize award. It was the perfect excuse to travel to a city we both fantasized about. Once there, we tried collaborating on a meta docu-fiction project involving ourselves as actors. It didn’t work out. We went our separate ways and wished each other good luck. I then thought I’d do what I had always wanted to: apply my street photography approach to documentary filmmaking. With no preparation required, I was shooting for about two weeks in the streets of Tokyo — a liberating experience.

M: What do you think the film says about Tokyo and its inhabitants?

ST: I could discuss with you what I find interesting about each subject, in each moment, but I couldn’t tell you what the film says about Tokyo’s inhabitants in general. I don’t like generalities and I surely wasn’t trying to make one with this film. My filming process goes against it, as I simply observe, curiously, without imposing a judgement. When I see the slightest breach onto a thought, an intimate space, I frame the shot almost instinctively. It’s what lies beyond the words that excites me, and it’s ultimately what I intend to make the film about.

Now, I could tell you about my experience hunting for those moments and compare this experience to other cities, but that’s not what the film tries to say. The film doesn’t try to say anything, it only tries to understand. I did find emotions to be rarely displayed in public, as Japan seems to have a strong code of etiquette. Roland Barthes once qualified Japan’s approach to politeness as “sacred.” But this constituted an exciting challenge for me; I was hunting for cracks on a thicker glass.

M: I noticed that colors were represented in different ways throughout the film. Such as the yellow trees on the street and then the shot of the man wearing a yellow jacket on the train. Was this intentional?

ST: That wasn’t intentional, but I love the fact that you are making those associations for yourself. Have your own experience of it; see things I haven’t seen, that’s great, that’s the film having a life of its own, communicating to people in different ways. Just like a photograph would.

M: You live in London now. Do you think the colors of Tokyo and atmosphere are different from European cities?

ST: Tokyo is very photogenic; I find it more colorful than London. I love the softness of Tokyo’s streetlights, their blue tones, contrasting with the warmth of china balls sometimes decorating the front of shops and restaurants. It’s visually engaging and very cinematic. A friend actually compared those streets to a film set, as if they were carefully designed to create that mood. But that’s more specific to quiet areas at night, like Asakusa, which I enjoyed very much.

If you start exploring Akihabara, Shibuya or Shinjuku, then it’s another story. Those are so much brighter than any European cities I’ve been to. All of that outdoor advertising, overlapping light boxes, colored neon lights, it’s quite stimulating and definitely contributes to the dynamic feeling Tokyo gives you. Although there’s magic to it, it can also be a little overwhelming, especially if sound comes with it. I entered one of those slot machine centers once, oh my, you could murder someone in there and no one would hear.

M: What’s your favorite scene in Spirit in Tokyo? I love the scene where the salaryman smashes his umbrella outside the station. For me it represents the frustration and need for release that comes with living in Tokyo.

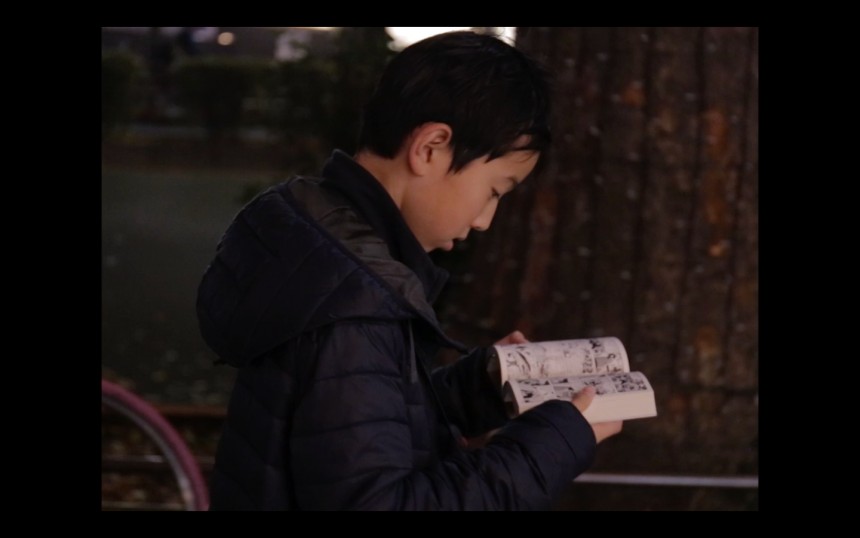

ST: The walking kid immersed in his manga probably. I love how he loses himself in his book, how absorbed he is by it, while his surroundings are loud and busy. His face wears that innocence and deep concentration. I find it quite beautiful.

Yes, the drunk man repeatedly smashing his umbrella is an intense one. It was the first time I witnessed someone publicly expressing anger in Tokyo. As I framed him, I started questioning the limits of my filming, the ethics of it. Was it right to capture someone so desperate? It felt a little wrong, but at the same time the peculiar way with which he was releasing his anger, hitting his umbrella in silence, seemed to reveal something bigger about Japanese society. I don’t think I would have recorded someone shouting and going crazy, but here, he was channelling all his anger into this one repetitive movement, it was so self-contained, so methodical, almost respectful in a way. That’s how well-behaved Japanese are, even the angry man shows respect. even the angry man shows respect.

M: Are you a fan of Japanese film? Are there any Japanese films or directors that inspire you?

ST: I love Akira Kurosawa’s work. His mise-en-scène is inspiring in its effectiveness to create dramatic tension. His composition and staging are so carefully designed to engage the viewer, with such a great attention to detail. What I find extraordinary is how all the elements present in his frames cooperate to tell the story; none of them seem to be superfluous. That’s probably the main reason why he’s considered by most as one of the greatest visual storytellers of all time. His work has definitely played an integral part in my artistic growth.

M: You’re a graduate of the London Film School. What was that experience like? And what future plans do you have?

ST: The London Film School has been both a frustrating and exhilarating experience for me. For two years, I was able to train in a full range of filmmaking skills (directing, lighting, editing, sound recording, etc.), developing strong technical knowledge and an in-depth understanding of the entire process. With the few projects I directed there, I could experiment with the medium in a safe environment, receive constructive feedback and learn from others. But the film school framework can also be creatively oppressing at times: working on specific briefs with specific rules, being provided with a limited amount of film stock to train your shooting discipline, working on someone else’s project for months, etc. So I would work on extra-curriculum projects. Spirit in Tokyo was one of them. I had no briefs, no rules. It was liberating.

My graduation film Natural Paul, a 24-minute downbeat comedy, is currently starting its festival run, which is exciting. On the work side, I continue freelancing for some production companies, and I’m now meeting with advertising agencies.

I often think about going forth with another street project. In the meantime, I channel those pulsions into my Instagram account (@tibistreet), which is exclusively dedicated to street life gems.