One afternoon, I cut, chopped, boiled, and mixed the ingredients for beet caviar. While I prepared this traditional recipe I learned while living in Kazakhstan as a Peace Corps volunteer, my host mother Larissa joined me at the counter. Her smile shined with that single gold tooth, and her usual flower-print dress flowed around her large frame. Both of us worked along, content to be together again as the dish took shape before us.

Larissa did not really visit my apartment in Tokyo. Rather, her ghost—my memory of her—did. It’s been nearly 20 years since I hugged her farewell at the bus station in Kapchagay, a small town on the steppe just north of Almaty. Her form became blurrier with my tears and the waves of heat rising from the sun-blasted sand, until it disappeared with a turn of the road. However, when I make that recipe, she appears.

The same is true with other dishes and other people, each linked to me from some time or place in my life. It is, I like to think, a sort of “fusion cooking,” where the ghosts of the living and the dead join me in my kitchen, wherever it might be, reinforcing bonds despite distances of time and space.

Like Larissa, my mother promptly appears to help skim the foam off bubbling strawberry jam. As I ladle hot fruit into jars, she begins a story about the Wisconsin farm where she grew up. Snippets of the German dialect she spoke to the workhorses sprinkle over her tale. I can almost catch the scent of hay and sweet silage mingling with the fragrant jam.

As the zucchini bread emerges from the rice cooker (my tiny apartment doesn’t have room for an oven), Grandma Lambert, white hair freshly permed and primped, inevitably pulls up a chair. While the bread cools, her sisters, my great aunts Esther, Ruth, and Viola, come crocheting, cold glasses of beer and cigarettes on the table next to them. Great Uncle George, their beloved younger brother, soon pokes his head around the corner, too. I offer him my chair and settle on a low stool to soak up their banter.

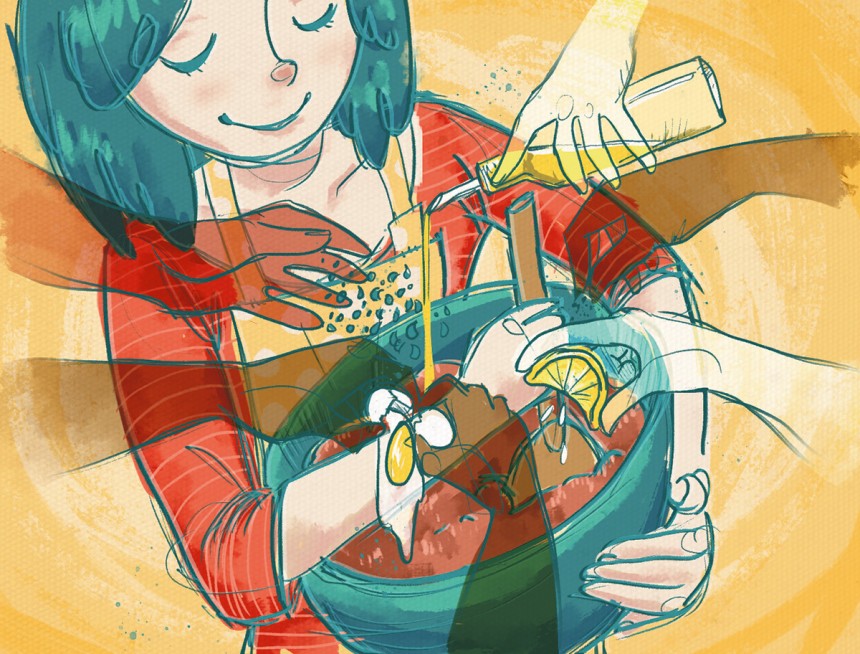

Tabbouleh brings my Lebanese neighbor from Michigan to supervise. As I chop the parsley, Maan shakes his head and says, “Not yet. More.” I keep chopping, attempting to imitate the way his practiced knife neatly and rapidly dices everything it meets. He nods in approval as I liberally douse the onion, garlic, bulgur, parsley, and tomato with olive oil and lemon juice, finishing with a hearty pinch of salt. I plunge my hands in and mix; it is, according to Maan, the only way to do it. So even here, thousands of miles away and 13 hours ahead of him, I do as I’m told.

Homemade bread, as is often the case, beckons a crowd. Uncle Bob, his golden loaves the standard I aim for, peers over his glasses as I mix yeast, honey, water, and flour for the starter. While I knead the dough, a multitude of young cousins traipse through to see when it might be done. The smell as it bakes brings my friend, Amy, as her two girls chase each other around the kitchen. My mother pops in for the first warm slice, butter pooling on the grainy surface, a jar of jam in hand.

A bowl of warm goma ai shungiku (sweet sesame chrysanthemum greens) conjures Takashi and Shizue, the organic farmers I worked with in Tokyo nearly every day for five years. Keiko Nakagawa, owner of the onigiri shop where I spent many evenings sharing stories, learning recipes, and practicing Japanese, helps prepare jars of homemade umeshu (plum wine) for steeping. Her death three years ago from cancer is still painful to recall.

And there are countless more. Grandma Gail (deviled eggs with dill), Grandma Wegner (fruitcake), along with beloved friends, Rocio (black beans and homemade tortillas), and Sybil (cabbage soup). Each dish and recipe is part of a delicious life menu that reminds me of who I am, where I’ve been, and the people I love. My kitchen becomes a pleasant mix of past and present, a potluck party where my ghosts gather and mingle to share good food and stories. I sip and nibble, remember and smile, grateful for this banquet, these friends and memories. It’s the best kind of home cooking I can imagine.