April 10, 2017

Invisible Lines

How the Yamanote and Shitamachi divide formed modern Japan

Japan is a land of contradictions where futuristic skyscrapers stand in close proximity to old wooden houses and apartments with no central heating. It is a country where suit-clad engineers share trains with working-class women wearing traditional kimonos passed down through their families for generations. But when you look closely, you will see that those supposed inconsistencies do have one thing in common: They both embody the spirit of Yamanote and Shitamachi.

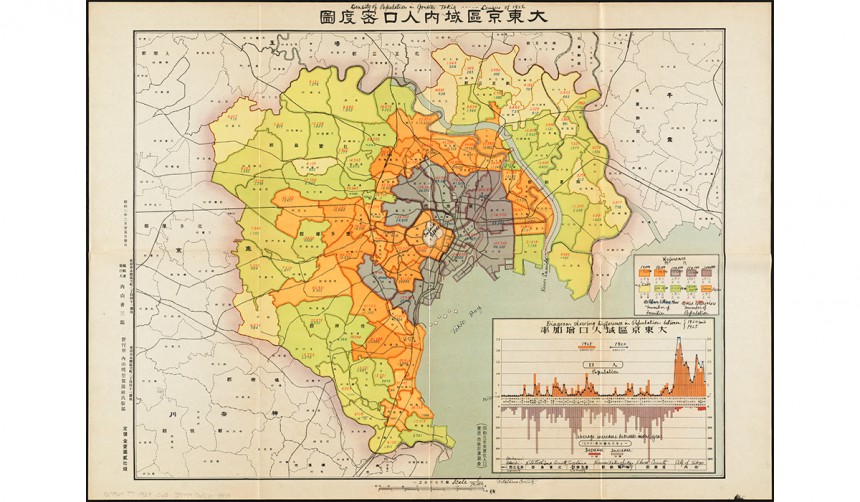

Let’s back up a little. After Tokugawa Ieyasu finished unifying Japan and moved the seat of government to Edo (which would later become Tokyo) in the early 17th century, he set up his vassals and feudal lords in the spacious, hilly area west of Edo Castle. On the other hand, merchants, craftsmen and the like were restricted to the eastern parts of Edo around the Sumida River because, while the upper class did acknowledge the usefulness of commoners, they didn’t particularly want to look at them.

The rich, affluent area of samurai residences, rich temples and beautiful gardens soon became known as Yamanote (“mountain hand(s)”). At the same time, the narrow, grubby streets full of restaurants and other places of commerce gained the name Shitamachi (“under-town”), but only because the aristocracy felt that “crap town” would have been too much on the nose. That’s not to say that “crap town” wouldn’t have been somewhat justified, seeing as how, at the time, Yamanote was the only area of Edo that actually had a working sewage system.

Over the next few centuries, Yamanote and Shitamachi developed their own distinct cultures, one sophisticated and modern, the other traditional and folksy. Both existed in the same city but always gave each other a wide berth right up until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. This political upheaval took the power from the shogunate and gave it back to the emperor, who then ordered many samurai and feudal lords to return to their original land holdings out in the country. This, by some rough estimates, vacated over half the area of Yamanote. And once the Meiji oligarchy decreed that all social classes were now equal, those unoccupied areas of Yamanote were quickly bought up by rich, lower-class merchants from Shitamachi, all while their blueblood neighbors lamented about how the world was coming to an end, presumably.

Then, the end of the world came. Or, at least, it felt like that.

In 1923, the Great Kantō Earthquake devastated large parts of Tokyo and Yokohama, resulting in over 140,000 deaths. The damage was so great that the government actually considered moving the capital to someplace that didn’t look like the more rundown parts of Hell. But instead, the Japanese people persevered and rebuilt the city. The one thing that never really returned to its former glory, though, was the stark divide between Yamanote and Shitamachi.

In the hustle and bustle of the reconstruction effort, Shitamachi people made one of the most significant encroachments on the former Yamanote territory, leading to an unprecedented mixing of the two cultures…and, subsequently, the creation of modern Japanese.

Hyōjungo (standard Japanese), is the “official” version of the language taught across the country and the world, and it is primarily based on the Yamanote dialect. But many of those influences are nowadays considered overtly polite and could even be seen as sarcastic rudeness, such as using “gomen asobase” rather than “gomen nasai” for “sorry.” Conversely, many parts of the Shitamachi dialect have infiltrated hyojungo over the years, creating the everyday version of the language that you actually hear on the streets, like affixing “BU” to verbs (“bukkakeru” [splash], “bukkorosu” [kill]) to add emphasis. Also, in a relaxed conversation among friends, it’s hard to find a person who doesn’t occasionally change the “ai” sound to the Shitamachi-esque “ee” like when “itai” [to hurt] becomes “itee” or “shiranai” [I don’t know] changes to the more casual “shiranee.”

Nowadays, Yamanote and Shitamachi cultures have found themselves in a strange symbiosis where one side still sees the other as pretentious or crude, all while not realizing just how much they have intermixed. You can see it not only in the language but also in some of the Yamanote and Shitamachi areas. For example, Roppongi, located in the supposedly Yamanote area of the Minato Ward, could not seem more sophisticated and modern, but if you venture just slightly behind the scenes, you’ll find it full of lively dive bars and strip clubs that are the definition of Shitamachi.

That’s why it’s not actually fair to say that Japan is the land of contradictions. Rather, it’s a place where both high and low cultures remain separate on the surface but actually interact in all sorts of ways to create a balanced mix of the two. For a country with such a long history with Buddhism, it wouldn’t be far off to call it a kind of Middle Way.