When people think about Japanese literature they’re probably thinking of Haruki Murakami. But one giant does not a nation make, and if Murakami isn’t your particular cup of sencha (or you’re just looking for something different), there’s so much going on in Japan’s diverse literary scene that there will definitely be something else to suit.

The following books have all been translated into English.

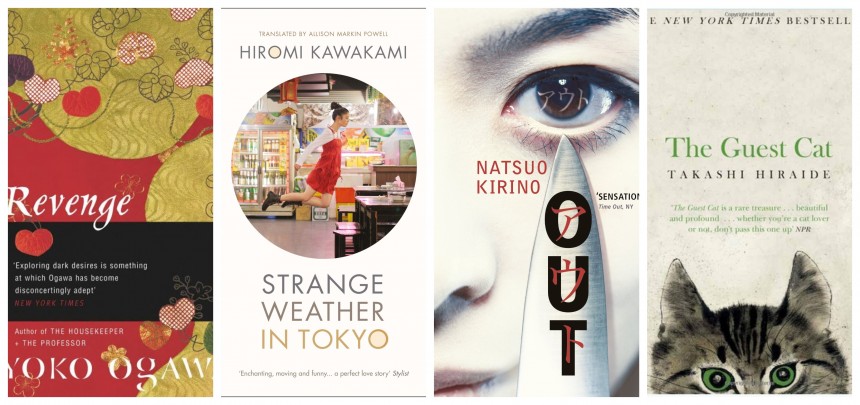

1. “Out”

by Natsuo Kirino (translated by Stephen Snyder)

The twist in Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl” is now famous, but more lingering is, perhaps, Amy’s bitterly incisive and too-accurate speech about “cool girls.” Two years later Paula Hawkin’s “The Girl On the Train” was hailed as the next blockbuster thriller that also explored real, female psychology without the flat cookie-cutter characters so common in the genre. But while these books exploded in the West only in the past five years, Natsuo Kirino was there first.

Her first crime novel, “Out,” centers around four women working graveyard shifts at a bento factory who struggle with family, relationships, and domestic responsibilities. When one woman strangles her layabout husband in a fit of anger, she enlists the help of the others to dispose of the body. “Grotesque” starts with the death of two female prostitutes, Yuriko and Kazue. Yuriko’s younger sister takes over the narration, and what unfolds is a chillingly deep and unflinching look at the monstrousness of female beauty and its status as currency in the world. Speaking at the Tokyo International Literary Festival in 2015, Natsuo Kirino mentioned that rather than choosing to write thrillers or crime novels, she first and foremost wanted to write realistically about women. The thrillers just came out of that impulse.

2. “Strange Weather in Tokyo”

by Hiromi Kawakami (translated by Allison Markin Powell)

“Strange Weather in Tokyo” (also known by its alternative English title “The Briefcase”) has descriptions of food so tender and rich you’ll be homesick for Japanese izakayas even if you’ve never been. The story sustaining these lovingly portrayed pleasures of daily life is a similarly tender, simple love story—between a single woman in her thirties and a teacher in his seventies. Though set in the real world, Kawakami makes plenty of room for the magic and connections of dreams and the unconscious. Like a more understated Murakami or more surreal Banana Yoshimoto, Kawakami’s writing is unusual in its ordinariness. She deftly and sympathetically portrays loss, loneliness, nostalgia, and complicated happiness in her everywoman characters.

“Manazuru” and “The Nakano Thrift Shop” have also been translated into English.

3. “The Guest Cat”

By Takashi Hiraide (translated by Eric Selland)

Cats are all the craze in Japan lately; a stroll through any convenience store or bookstore will show you no shortage of photobooks, calendars, and even magazines wholly devoted to these irresistible pets. Natsume Soseki’s “I Am A Cat” has always been the premier cat-novel of Japan, but Takashi Hiraide’s novel “The Guest Cat” makes a convincing case for honorary mention.

In “The Guest Cat,” a writing couple lives together in a quiet part of Tokyo. One day, a neighbor’s cat wanders into their home and gradually instills herself into their lives. This writing couple is Hiraide and his wife; the novel he is working on— “The Guest Cat.” First and foremost a poet, Hiraide suffuses this novel with profound insights in succinct, memorable, and sunlight-dazzled sentences. In its simplicity and profundity, “The Guest Cat” is an excellent example of slice-of-life, a genre Japan does especially well.

4. “Revenge: Eleven Dark Tales”

By Yoko Ogawa (translated by Stephen Snyder)

The first story in “Revenge: Eleven Dark Tales” takes place in a bakery in the corner of a quiet town square on a lazy afternoon, a peaceful and nearly-universal scene. The flight from afternoon bakery to death happens so quickly and subtly you almost miss it—but then it’s too late, the sun is gone and you’re left in a cold and empty place where regrets and tears flutter amid unexplained mysteries. Which is all to say: Ogawa is a master of atmosphere, and her technical range is immense.

Particularly celebrated for her short stories, her collections “Revenge” and “The Diving Pool” take stories of ordinary, often psychologically alienated protagonists and take us into their madcap world where the surrealism is both psychological and just-possible: finding, for example, carrots in the shapes of hands or an abandoned post office filled with rotting kiwi fruits. Her novel “Hotel Iris” takes the subtly creepy elements she is known for and expands them into a longer, more psychologically developed plot about a young girl whose family owns a hotel and a compellingly seductive Russian translator. “The Housekeeper and the Professor,” on the other hand, is laced with elegant and beautiful descriptions of mathematics between a warm family story about a housekeeper, her son, and a mathematics professor with a short-term memory retention of only 80 minutes.

5. “Night on the Galactic Railroad”

by Kenji Miyazawa (translated by Julianne Neville)

A well-known poet and children’s author from the early 20th century, Miyazawa is a beloved author who has left a lasting legacy on Japanese literature. His novel “Night on the Galactic Railroad” is a short fantasy following a young, impoverished boy, Giovanni, who boards a train traveling through the Northern Cross and numerous other stars in the Milky Way. Likened to a Japanese Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s “The Little Prince” for the intricacies and big ideas taken on with a children’s book’s fantasy and charm, “Night on the Galactic Railroad” stands on its own as a moving and imaginative tribute encouraging strength and perseverance in the pursuit of happiness.