August 2, 2019

Across Space & Time: Translating ‘Night on the Galactic Railroad’

Kenji Miyazawa's untranslatable masterpiece

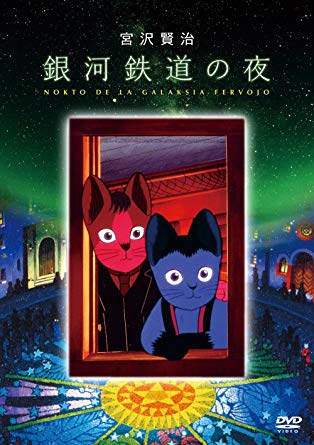

It’s been both more and less than 85 years since Kenji Miyazawa’s masterpiece, “Ginga Tetsudou no Yoru” (銀河鉄道の夜), was published posthumously in 1934.

Translated alternately as “Night on the Milky Way Railway,” “Night on the Galactic Railroad” and “Night Train to the Stars,” the novel underwent many different versions. Miyazawa (1896-1933) wrote, rewrote, and wrote it again, and again; the version commonly used by scholars is at least the fourth version that he composed.

It’s a novel that defies clear identification with any one time, place, or ideology. “Ginga” is ripe with Buddhist imagery and echoes of Miyazawa’s rural hometown in Iwate Prefecture, yet it seems to take place in Christian Italy. It wasn’t translated into English even once until 1996; since then it’s been translated at least four times with dramatically different tones, registers and styles.

Ginga’s protagonist, Giovanni, has a sick mother, an absentee father and is bullied in school. Along with his friend Campanella, he boards a magical train that soars into the depths of the Milky Way on its way to heaven. Along the journey they stop at the five million-year-old Pliocene Coast, birdwatch in the fantastic Swan Zone, cross over Connecticut and Lancashire and encounter the dead of the sunken Titanic. The story is perhaps best-known for its haunting and tragic ending, when Campanella is found to have drowned in a river, and Giovanni is left alone.

Miyazawa’s fierce preoccupation with death is enough to defy the book’s common label as children’s literature. His writing is dense, chock-full of scientific detail, popping with improvised onomatopoeia and woven throughout with threads of stream-of-consciousness. And the entire novel is underscored by his nuanced concept of a Fourth Dimension, the daiyojigen (大四次元, lit. “fourth dimension”).

“Ginga” has enthralled adults and children and puzzled scholars in Japan and abroad for 85 years — both a little more than that, and a little less. How do you translate a work that crosses such vast expanses of space and time, much less a work like “Ginga” that doesn’t seem to have much of a time or place to begin with?

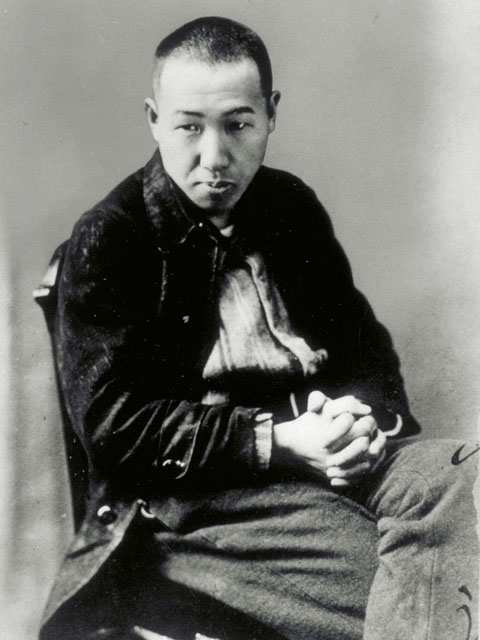

Kenji Miyazawa, Japan’s great rural novelist

It’s hard to overstate Kenji Miyazawa’s significance and fame in Japanese culture. His novels are read by children in school, adapted into popular animated films and studied and re-studied by academics.

His shadow extends not just over Japanese literature, but over film, anime, manga, art and agriculture. “His vocabulary and style are really unique and original,” said Koji Toba, Professor at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Waseda University. “‘Ginga Tetsudou no Yoru’ has become a source of imagination in contemporary culture and subculture.” A few of his many literary innovations include borrowing words from German and English and combining them with Japanese kanji, inventing hundreds of new onomatopoeia and utilizing local Iwate Prefecture dialect.

Miyazawa was also a professional agronomist, amateur geologist, Buddhist scholar and rural activist. His ecological and humanistic impulses can be seen in his most famous poem, “Ame ni mo makezu” (雨ニモマケズ or “Undefeated by the rain”), a poem known by many Japanese from an early age and transcendent in its selfless simplicity.

His status as a rural author makes him unique among modern Japanese novelists, who were almost entirely based in Tokyo. Keenly focused on the provincial and natural world, Miyazawa once said that his writing wasn’t his own creation — that the words came to him from the landscape.

But Miyazawa lacks the fame, readership and scholarly emphasis in the West compared to authors of similar significance within Japan, like Yasunari Kawabata and Yukio Mishima. “His popularity does not at all rub off in the US, despite translations of his poetry becoming widely available since the 1960s,” said Hoyt Long, Associate Professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Chicago. “It’s surprising because his work travels so much farther than his local region.”

Translating “Ginga,” where and when you can

Does translating “Night on the Milky Way Railroad” seem daunting yet? It certainly was to Sarah Strong, Professor Emeritus in Japanese Language and Literature at Bates College, who wrote a heavily annotated translation published in 1991. When translating “Ginga,” her goal was to get the English-language reader to feel the same way she did reading the text in Japanese. To ensure that her own feelings about the text were shared by a Japanese reader, she collaborated with a colleague to check her work and hone in on the core emotion behind every sentence, every line.

“If something was weird, I wanted the reader to think, ‘that’s weird,’” Strong said. “What was funny? What was happy? What was sad? I needed to get as close as I could to really understanding the writing.”

It’s a wonderful approach to translation that faces practical complications. There are abundant roadblocks to translating Japanese literature of any kind. I asked several translators, including Philip Gabriel, translator of several Haruki Murakami novels, and Eric Selland, best-selling translator of Takashi Hiraide’s “The Guest Cat,” about these issues. Linguistic challenges begin with divergent grammatical structures and Japanese’s persistent lack of subject, the “you” or “I” central to any English sentence. Hardly to mention Miyazawa’s made-up words and regional dialects.

Meanwhile, cultural challenges start with simple but untranslatable differences like how college students in Japan take long vacations from January to March, not June to August like they do in the western world. Translating Kenji’s layered Mahayana Buddhist imagery makes translating genkan or engawa, Japanese entrance hall and veranda respectively, both unfamiliar to western audiences, seem like a walk in the park (or a walk to the temple).

Strong tried to cut through the noise. She said that she focused on the feeling behind the piece. “You have to look at Kenji’s emotional motivation in writing this story,” she said. “His sister died the year before [he started writing]. Kenji is asking himself: where is she now?… He’s trying to place her within a Buddhist cosmology.”

But when you focus on feeling alone, you ignore the texture of the text — the lively onomatopoeia, the stream-of-consciousness haze — the sonic energy that deeply affects the reading experience.

Towards the middle of the story, Giovanni watches the spinning wheel of a weather station at the moment of his passage from the real world into the fantastic world of the Milky Way Railroad. The scene is full of onomatopoeia and sound effects that are quickly lost in translation. Take a look at a literal gloss of the text alongside Strong’s translation:

そしてジョバンニはすぐ後ろの天気転の柱がいつか

And then Giovanni right away the behind weather station wheel at some point

ぼんやりした三角標の形になって、しばらく蛍のように

vaguely [onomatopoeia]-did triangular shape becoming, it now like fireflies

ペカペカ消えたりともったりしているのを見ました。

twinkle-twinkle [onomatopoeia] turning off and back on and so on [it he] watched.

それはだんだんはっきりして、とうとうりんと動かないようになり、濃い鋼青色

That bit-by-bit clearly [onomatopoeia] doing, at last not moving becoming, steel blue

の空の野原に立ちました。

sky’s field on [it] stood.

Giovanni noticed that the pillar of the weather wheel directly behind him had turned into a sort of hazy triangular marker. For a while he watched as it pulsed on and off like a firefly. It gradually grew more and more distinct until at last it stood tall and motionless against the deep steel-blue field of sky. (Strong)

In the Japanese, Miyazawa inundates a reader with not only images but also sounds: the sound of fumbling indistinctness (bon-yari), the sound of a faint or dulled glitter (peka-peka), the sound of haziness becoming clarity (ha-kiri), and one sound that simply puzzles and seems to mean nothing in particular (rin). Sonic energy defines Giovanni’s passage into a new world. Strong’s translation is beautiful and not inaccurate, but does not capture this dimension of the text. Neither does Roger Pulver’s.

“Sometimes I translated too far away from the text,” Strong said. “When I look back at [my translation] I sometimes say, “that’s too strong” — it’s okay to go back to the more limited words of the original.”

To the fourth dimension and beyond

Long explained that the daiyojigen is not simply the addition of time to our three-dimensional universe. “For Kenji, the Fourth Dimension is a whole new axis — a way to jump to a higher plane,” he said. “He’s thinking about Iwate Prefecture as part of a multi-layered, multi-dimensional universe.”

Uncertain setting, nuanced tone, resounding sonic energy, a backdrop of tragedy, confounding religious allegory. Miyazawa is referred to as a children’s author, but surely we can’t translate him that way, not once we become aware of all these complexities.

Leith Morton, a translator of Miyazawa and Professor Emeritus at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, said that translating Miyazawa’s different shifts in tone, register and voice is a demanding effort. “Do you adopt a folk-tale style of narration or do you go for something different?” he asked. “[Miyazawa] is closer to the Grimm Brothers than Roald Dahl… Manga and animated versions of “Night on the Milky Way Railroad” are always prettied up, but his original tale is much more than this. Death and reincarnation are perennial themes in his work.”

The various beautiful but flawed translations of “Ginga” are a part of its complex and ever-evolving identity. Long agreed that there would be a place for a new translation, especially one that could reconcile the novel’s childish wonder with its four-dimensional complexity. “How do you render the story not just as children’s literature?” he asked. “How do you create a language that serves but isn’t written strictly for a younger audience?” You could translate “Ginga” a dozen more times and still not exhaust the challenges and possibilities.

The state of Japanese literature in translation as a whole has come a long way. In the 20th century, translations were often completed by academic scholars who lacked a sense for literary English. Translations accordingly came out formal, bogged down. Selland believes the field is in a good place comparatively.

“There’s a mini-boom in Japanese literary translation,” he said. “Some people feel that there isn’t enough women’s writing out there, but because of that concern this is actually the area that’s growing the most.”

Gabriel added that the recent winners of the most prestigious literary prizes in Japan — the Akutagawa and Naoki Prizes — were women, and that all the nominated novels were written by women. “It’s great to see the variety of writers and genres that are being given a chance to find a readership in the West,” he said, “though it is still a challenge to promote writers that are new to Western editions and publishers.”

If we can learn anything from “Ginga” 85 (more or less) years later, it’s that we should refuse to settle in one place, time or ideology. The beauty of translation is that it connects the contemporary place and time of the translator to the foreign, distant place and time of the author — a Four Dimensional line, bridging the gap between two worlds.

“Ginga” gives us all a way to escape the limitations of our time, our place, our ideology, our identity. A good translation does the same.

Feature image source: © Asahi Shinbu-sha / TV Asahi / Kadokawa Pictures