April 27, 2017

What Charley Longfellow Saw

The forgotten story of a restless traveler who was one of the first Western tourists to explore Japan

Charles Appleton Longfellow — Charley, as he preferred to be called — came to Japan on a whim. But the country profoundly changed Charley Longfellow, and its memories seemed to haunt him. Today, much of the art and household wares he collected in Japan survive either at Longfellow House or as part of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts’ Asian Art collection. Many of the same vistas Charley beheld are still there, despite two wars, a major tsunami and an endless string of earthquakes.

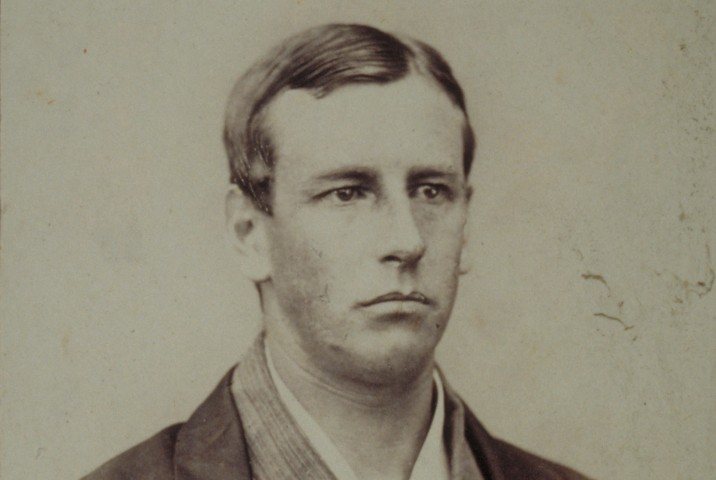

He was one of poet and educator Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s children, born into Boston high society and well acquainted from a young age with the New England luminaries of the mid-19th century. Charley remains largely obscured in his famous father’s shadow. Meaghan Michel, a US National Park Service Ranger who has volunteered and assisted at the Longfellow House — now a national park — is a leading authority on Charley Longfellow, one with whom I have frequently compared notes as a scholar of the Edo-Meiji transition, which Charley saw firsthand.

Even for Michel, learning about Charley was a complete accident. She stumbled on his name in the midst of research about Henry Longfellow and his friend Senator Sumner. “I never expected that to just be the tip of the iceberg for him,” she muses. Charley, like several other members of his family, lived in the house, but according to Michel, he is “the Longfellow family member that no one knows going into the house, but everyone remembers when they leave.”

Henry Longfellow called his son an enfant terrible: somehow Charley was always getting into mischief. Some of it was near fatal, as in the gun incident when he was 11 years old that left him without a left thumb. Against his father’s wishes, Charley snuck away from home to enlist in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He received a commission as a cavalry officer in the First Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment and quickly earned a reputation — despite the missing finger — as a crack sharpshooter.

His war over, Charley yachted to England in 1866, a trip that briefly clinched him the world speed record for an Atlantic crossing. Later still, he toured Europe and South Asia. Despite a brief return home to New England, Charley did not stay long. On June 1, 1871, his father received a brief telegram from San Francisco. One imagines the elder Longfellow was shocked as he read:

Have suddenly decided to sail for Japan today. Good bye. Send letters to the Oriental Bank Corporation, Yokohama. –C. A. L.

* * *

Charley Longfellow, Civil War veteran and restless traveler, crossed the Pacific on a whim and arrived in Japan on June 25, 1871.

Like many gentlemen travelers of his time, he came to Japan independently wealthy, but the similarity ended there. He was not there to merely observe from an aloof distance. Charley immersed himself in Japanese culture, engaged with the people, and learned to read, write, and speak the language — the latter a remarkable feat when one bears in mind his disdain for rules of spelling and punctuation in English. In Japan, Charley Longfellow seemed to come alive.

He was a hard-partying, ever-curious, energetic force in the Tokyo-Yokohama area in general and the foreign community in particular. He befriended young former samurai, a few of whom, such as Mitsubishi founder Iwasaki Yatarō, were increasingly influential in early Meiji Era society. Quickly making the acquaintance of American Minister-Resident Charles De Long, Charley accompanied the minister on diplomatic business, including an audience with the young Emperor Meiji. It was in De Long’s company that Charley traveled north to Hokkaido, nominally as the minister’s temporary secretary, in September 1871. After a brief stint in the north, the American diplomatic delegation crossed the Tsugaru Strait in early October and began a leisurely descent of the Oshu Highway, setting off from Sotogahama for the long journey back to Tokyo overland.

When Charley Longfellow saw northern Honshu — the Tohoku region — in 1871, it was still recovering in the wake of the Boshin War. The war pitted a coalition of northern clans, which styled themselves the Northern Alliance (Ouetsu Reppandomei), against the nascent Imperial Army. Far from the popular portrayals of sword versus gun, the Alliance used cutting-edge weaponry in its fight, including Gatling guns, but was unable to hold its ground. After savage fighting, it lost, and the north was subjected to closer political scrutiny and military occupation than the rest of Japan.

The scars of war would’ve still been visible to Charley and the other Americans, but the land’s natural beauty and the resilience

of its humanity were also visible. Though Charley noted the poverty of some villages and towns during his journey, he also noted the positive changes since the war, from a baby boom in Morioka to plentiful shops and marketplaces in Sendai and beyond.

His appreciation was far from aloof. Charley’s own writing also tells us he made an effort to know something about the history and context of the places the entourage stopped. After passing through Shichinohe and Numakunai, the party arrived in Morioka on the October 18. During their stay, Charley also visited Morioka Castle, which had only recently been vacated by the Nanbu clan.

Not only did he inquire about its history, but his journal even notes that Nanbu Nobunao was its founder. Later, the party stopped in Sendai and after visiting Sendai Castle, took a sightseeing jaunt to the coast at Shiogama. There, Charley noted quite accurately the legend surrounding the name of both the town and its eponymous shrine: “This town we found derived its name from four large iron salt-boiling kettles sent down by the gods hundreds of years ago.”

Though he hadn’t been in Japan all that long, the country had left its mark on the young New Englander. In an era of superficial interest or exoticization on the part of other foreigners, and despite his former restlessness, Charley Longfellow’s genuine interest stands out all the more. In Hiraizumi, where Matsuo Basho mused on the summer grass that was long-gone Northern Fujiwara warriors’ only remnant, Charley wrote:

“We were told that on a mound nearby might still be seen traces of one of the old camps, but, after clambering up among the trees, we found nothing but a small shrine and fine view over the valley and the river now grown to a goodly stream and flowing placidly to the southward.”

As Michel explains, Charley was “not always poetic, but sometimes, there’s poetry in his words.”

* * *

Charley Longfellow never returned to the Tohoku region, but continued to travel elsewhere in Japan, and never ceased to be amazed by the sights he saw and the people he met. For a time he even tried to put down roots. He continued to study Japanese, built a house in Tsukiji, and even adopted Japanese dress. Though he’d been restless, there was something about Japan that seemed to deeply satisfy him.

But just as he began to do so, he was forced to leave Japan because of financial difficulties and family pressure, departing by steamer from Nagasaki on March 13, 1873. A letter sent from Shanghai to his sister Alice spoke to a profound change:

I have spent three weeks since my arrival in one round of dinner parties, concerts, private theatricals, etc… This gaiety is all very well in its way, but give me back my quiet, free, life in Japan. Lots of love to all. Keep sending my letters to Yokohama, as I may any day return there.

Your affectionate,

Charley san.

Though he would travel often over the course of his life, he returned to Japan three times. “I think every place he went had a profound effect on him,” Michel says, “but there was something about Japan that really stuck with him. He stayed there for almost two years and built a house for himself and his friends. There’s clearly some intent on his part to stay for a lot longer than he actually did … This is the man who literally explored the whole world for the majority of his life, but Japan was the place he found a home.”