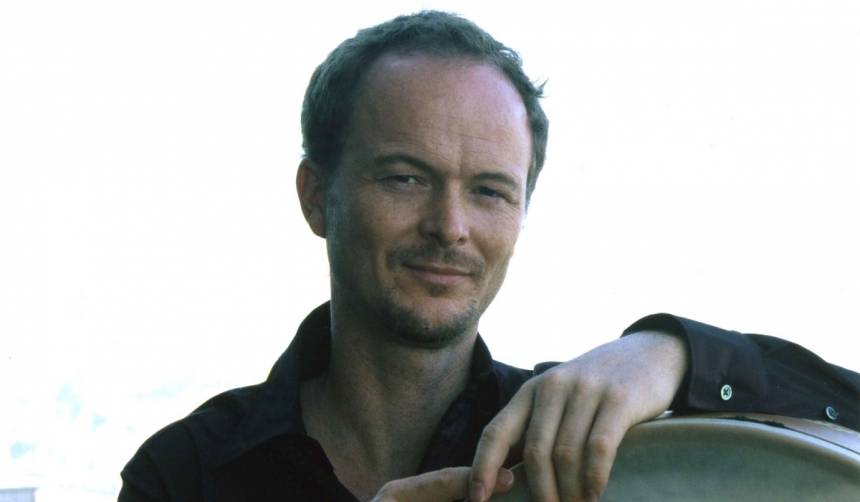

American percussionist Chris Hardy’s three-decade musical journey in Japan has taken him from the Nebuta Festival to the National Theater to the Cirque du Soleil. Metropolis heard from Hardy about the different ways the Japanese feel rhythm, and the experiences behind the latest album from his contemporary world/jazz quintet TGA.

How did you end up in Japan?

Although I was studying music at school, I was also interested in Buddhist art, Japanese language, and Arabic music. I pursued those interests by taking a few courses in those subjects, but music kept me pretty busy. In my last year at school, a group I was performing with toured Japan for six weeks. We traveled around quite a bit but our homebase was a small ryokan [Japanese inn] in Asakusa. I totally fell in love with Japan and made plans to come back. Original plans for a two- to three-year visit turned into a 27-year adventure.

What keeps you here?

Great opportunities to perform with fantastic musicians. The music industry is having troubles all over, so I think working from a base where you feel comfortable is important. Having lived here for so long, I have strong musical bonds and friendships with so many people.

As a percussionist, what is the appeal of Asia?

From a percussionist’s point of view, places like Brazil, Cuba, and West Africa—not Asia—are the usual first-choice destinations. I play a lot of hand percussion, so that made the choice even more questionable. Coming to Japan at an early age helped me focus as a person and musician. Asian—and specifically Japanese—aesthetics intrigued me and influenced my playing regarding the concept of “ma” and the notion of giving shape to what is not stated. This idea of space, even as a percussionist, is very appealing and inspires the creation of rhythms as beautiful and sublime as nature!

You play a wide range of styles. How does your background inform the different styles?

I started out on piano and then moved on to drums when I was 10. Growing up in Detroit, I was listening to a lot of funk, jazz, and rock music early on. One of my early teachers played drums and percussion for musicals that came to Detroit. He could play anything that came his way, and I went to see him perform all the time. My next teacher was with the Detroit Symphony and he eventually let me play as an extra with the orchestra. I attended the University of Michigan and really went out for anything and everything I could: orchestra, wind ensemble, West African drumming, jazz vibraphone, contemporary music …

Also a large population of Iranian immigrants were living in the Detroit area, and this sparked my interest in Persian and ultimately Arabic music, so much so that I contemplated going to the Middle East before coming to Japan. When I did arrive in Japan, however, Hamza El Din—arguably the most famous Arabic musician of the 20th century—was still active here and became my mentor. I was fortunate to be able to study and eventually perform quite a bit with him. Of course, I do like listening to so many different styles of music and really feel blessed to able to work and reside in those different musical worlds.

How did you get involved with Hitomiza, and what are the challenges playing with a puppet theater?

The opportunity to work with Hitomiza came [in 2012] with a joint venture between Nissay Theatre and Hitomiza. The composer for the project was looking for musicians who, of course, can read the score but also improvise with action on stage. Most of the work I do daily is very similar to this: I get the music chart with a melody, and I usually end up creating my own part, hopefully to suit the music. Performing and flowing with the dialogue in the proper context and learning the tempo and feel of each show is the most challenging task.

The schedule is very tight. We have five days to learn a show: one day where the musicians work with the composer, then four days working simultaneously with the director, puppeteers, lighting and audio technicians, [and] stagehands to get the show together. Moreover, the musicians are trying to memorize the storyline because there’s no time to consult the script while we’re playing. It’s a blur of activity, but great fun! The puppeteers are masters of their art and a joy to work with.

What was it like being a member of Cirque du Soleil Zed show?

Working with Cirque du Soleil was a fantastic experience. To be honest, I was not aspiring to be a musician in the circus but I took a chance at the right time and fully enjoyed it. The 60 performers in Zed were all Olympic-level athletes. Seven onstage musicians, two amazing singers, and 50 other technicians, totaling 120 people from 20 different countries working on every show. Of course, an environment like that does have its drama—but when everyone is in performance mode it really is magical. The audiences felt it too, and Zed remains one of the favorite shows among Cirque du Soleil fans. The music for the show was beautiful, and again, I was left to choose what I wanted to play. What a pleasure!

As a percussionist, what has been your relationship with traditional Japanese percussion like taiko?

My first exposure to taiko was seeing Kodo perform. I was totally blown away. When taiko classes were offered at school, I dove in only to find that it was Nagauta taiko that accompanies kabuki. This is fine, I thought; start formal, classical, and later move on to the informal folk and festival drumming.

When I moved to Japan, one of the contacts on the initial tour offered to let me play taiko at the Nebuta Festival in Aomori. He coached many of the bigger drumming teams. This is what I was after! The Nebuta Festival is one of the three big festivals in Northern Japan. The first year, I played for three days; on the fourth, I couldn’t lift my arms to even change my shirt. I trained for the next year and made it through. I continued for another five years and even bought my own drum, driving up to Aomori and back. I learned so much with these experiences and feel that I am versed enough to play taiko—but would prefer to play non-Japanese instruments on a professional level. Although I did play taiko for the Cirque show and on occasion play when it’s part of my setup.

Because I have a knowledge of the music, I am respected enough by some of the Nagauta musicians to have been asked to join them for special performances at the National Theatre. Another great experience was touring with Hayashi Eitetsu, an original member of Ondekoza, the group that later split to become Kodo. Eitetsu-san was a visual artist before becoming a drummer, and his shows are some of the most visually stunning and beautiful concerts I have ever seen.

Do you see any fundamental differences in the way Japanese and western people relate to rhythm, for example, the “downbeat”?

Between musicians, no. The average listener, yes. The older folks clap on one and three, the younger folks on two and four. One thing I would say is that Japanese audiences are the most attentive I’ve ever come across. Many Western musicians are a bit taken aback when a Japanese audience doesn’t react with the “proper” enthusiasm. If you talk with people after the show, though, you know they were taking in every detail and are very knowledgeable listeners.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve faced as a foreign musician in Japan?

Remain creative and maintain identity without being pigeonholed. There aren’t many cross-genre players here, and I really detest the whole genre-categorizing aspect of the music business. The industry here is not open to musicians “crossing over” and this is perpetuated by musicians themselves. I’m primarily talking about jazz, rock, and pop musicians. It’s ironic because I don’t get that vibe from musicians who play traditional Japanese instruments. They may have a 300-year familial lineage of playing traditional music, but are open to collaborate with artists outside of their own world.

TGA performs at Absolute Blue in Ikebukuro on Sep 24. http://christopherhardymusic.com