December 2, 2013

Ever and Never: The Art of Peanuts

A look at the man behind Charlie Brown

By Metropolis

Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on December 2013

As we headed to the Mori Arts Center Gallery to check out the Peanuts exhibition, I was nagged by slight pings of apprehension. While I was looking forward to seeing some of the original artworks that became characters we all know, I had the feeling that a museum in Japan would get it all wrong. With the Japanese preoccupation with all things cute, Snoopy is a big hit in the country. So I was worried the focus would be too much on Charlie Brown’s pooch rather then the other characters, or more importantly, the man behind them. Indeed the exhibition is called “Snoopy Exhibit” in Japanese. And so I was pleased to find that the extensive show presents a deep portrait of Charles M. Schulz.

It was interesting to see the original panels on which Schulz created his syndicated comic which ran in up to 2,600 newspapers for nearly half a century. The man created almost 18,000 of these, and there are countless samples in the exhibition. But the genius of the curators is in relating the popular comic strip to Schulz and his life. In one strip, Charlie Brown gets frustrated when his teammates abandon him in a rained out little league game and throws his baseball glove in a puddle. While this raises a chuckle, looking down at the display cases which holds Schulz’s childhood catchers mitt add sentiment to the entertainment. There are several examples of this type of display, showing, for example, that not only was Snoopy a die-hard astronaut fan, but Schulz was as well, with a prized possession on display being a commemorative pin carried into orbit especially for him by the Apollo 10 mission.

You learn a lot about Schulz in the course of the exhibition, including that he played on an amateur hockey team for nearly 30 years, was an inveterate golfer and had a dog named Spike who served as the basis for Snoopy. As is so often the case with larger exhibitions in Tokyo, the explanatory text is only presented in English for the introductions to each section. English speaking visitors, of course, can read the comics directly, without having to look down at the Japanese translations of each panel, but the commentary on each work is presented only in Japanese. So you can see Schroeder is such a Beethoven nut that he celebrates the composer’s birthday, but you will have to read Japanese to learn that this was also an annual event for the Schulz family, complete with cake and presents. Since the information likely came from the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California, it is a bit disappointing that it was not presented billingually.

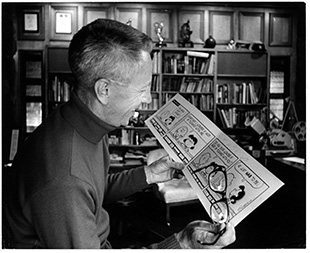

For anyone of the generation who was subjected to multiple viewings of “A Charlie Brown Christmas” every year, it is great to see some of the original animation cells of the classic. The main highlight of the exhibition is the recreation of Schultz’s studio, complete with discarded sketches wadded up and thrown in the paper basket. It is here we peer into the working space of a man who transformed himself from an art teacher to an American icon, and turned the disappointments and triumphs of his daily life into art.

Through January 5. Details.