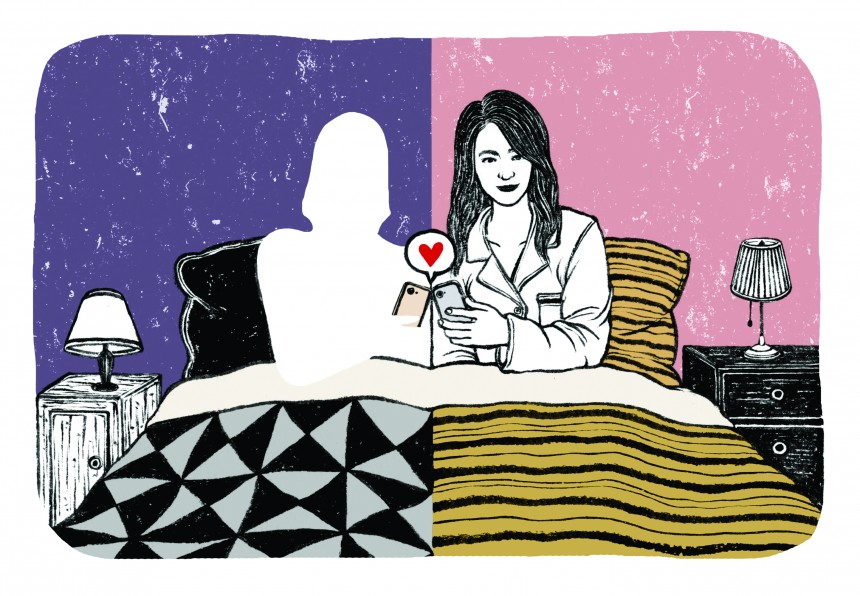

It’s a regular Friday night at home. Nestled in bed, I prepare to dive into a Netflix blackhole of my favorite shows that will most likely last until 4am. That’s when I hear it — the familiar ping from my phone signalling a new message from someone I matched with on a dating app. I know nothing about this person, save for a few fun facts listed in their bio. We exchange textbook pleasantries: “hey wyd,” “nothing much wbu,” then move along to tentative self-introductions, trying to get a better picture of the person behind the profile photo. Maybe one of us will crack a wise joke or use a witty pun that has the potential to turn into a cute inside joke. The conversation builds up to the inevitable ‘let’s meet for a drink at a dimly lit location’ stage.

But then the replies begin to take longer than expected and slowly but surely, the conversation starts to flicker like a worn out lightbulb, until someone puts it out of its pitiful misery by ceasing communication altogether. As quickly as the conversation began, it’s gone. The bubbling excitement that was once there is gone too, and left in its place is an empty shell of unfulfilled promises and lost potential.

Yet there’s this underlying sense of relief that it didn’t work out; it’s that type of relief you get from cancelled plans, knowing that you can avoid human interaction — for the time being. Perhaps this sense of relief is one of the reasons why some users ultimately resort to ghosting online.

Ghosting refers to the act of suddenly breaking off intimate relationships by terminating all contact with the other party, without proper justification or warning. It’s an act of flakiness, something that occurs all too often in the world of online dating. I would know because I myself am a serial ghoster. I’m guilty of forgetting to respond to people and failing to uphold conversations with perfectly decent matches online. I resort to ghosting so frequently, I might as well be haunting abandoned English manors in a lavish Victorian nightgown.

According to a recent study examining the association between breakup strategy and breakup role in experiences of relationship dissolution, I’m not alone; almost 72 percent of participants in the study have had experiences of being ghosted, while 65 percent admitted to having been a ghost. Ghosting, it turns out, has become an expected phenomenon in modern dating — an occupational hazard, even. Surely, the emotional effort to download, sign up and put yourself out there becomes pointless if you terminate any chance of a deeper connection. So why do so many people turn to ghosting?

To begin with, ghosting offers people a way to spare the other from direct rejection and may come from a place of attempted consideration rather than outright malice. Another factor to consider is the weight of obligation we owe to those we match with. To what extent should we be expected to interact with total strangers? In an age where technology offers access to millions of possibilities, it’s easier to dismiss someone — especially if there is nothing tying the two of you together, such as mutual friends or a shared locale.

Looking at a more fundamental angle, ghosting may be a symptom of a deeper issue — our inability to commit or maintain relationships, which in turn may be a result of experiencing constant exhaustion. The phrase ‘Millennial Burnout’ refers to the idea that pressures from various facets of life accumulate to burden people, especially the millennial generation, with a sense of perpetual fatigue. Exhaustion is a fatal addition when combined with warped expectations of romance based on picture-perfect portrayals of life on social media. We’re already tired of competing with societal expectations, being spread thin between feeling like we have to achieve certain life goals in a designated time frame, while thriving in all avenues of your life. When the payoff doesn’t come as quickly (or as abundantly) as we imagine, the urge to ghost someone is indeed appealing.

Of course, not all dating app endeavors end in ghostings; I’ve personally known a handful of success stories that have come out of matches online. As a queer woman in Japan, apps also help to navigate the relatively niche dating scene that is otherwise rather inaccesible in real life.

But the reality is that we have underlying commitment and expectation issues. And whether intentionally or not, a majority of us will become someone’s digital ghost. We can pretend that we want to build the perfect relationship but the first sign of questionable quirks and grammatical errors may be enough to scrap the chat entirely. We’re all complicit, in this world of harsh first impressions and trivially-made commitments — we’d rather bemoan our single fate than do anything proactive to change it. And personally, I’m a little relieved by that. It means that we’re all imperfect, we all make mistakes and that’s what makes us human.