March 24, 2018

High Contrasts, Soft Explosions

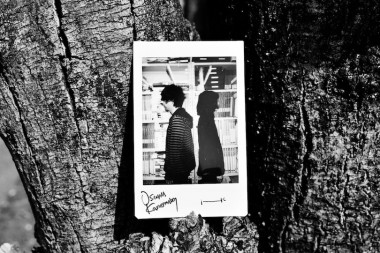

Tokyo-based cult photographers Osamu Kanemura and Hiroko Komatsu

By Erin Nøir

We picked the brains of Tokyo-based cult photographers Osamu Kanemura and Hiroko Komatsu and delved into the intricacies of their work.

Osamu Kanemura—Intensifying the grain

Osamu Kanemura started his career in photography in 1989 when Tokyo was at the height of its economic bubble. Kanemura found inspiration and a recurring subject in the period that followed and the struggles Japan faced as it entered economic stagnation in the early 1990s. These themes would continue to appear in his works long after Japan’s “lost decade.”

“At the time, Tokyo’s landscape was extremely unbalanced, with empty lots beside towering skyscrapers. It was a crazy time,” Kanemura recalled vividly.

For Kanemura, Tokyo today may have recovered from that period, but the urban disorganization of this era remain. “Beautiful Tokyo is a lie. The dark side of Tokyo is what’s true,” he added sternly.

Kanemura draws his inspirations from Western, mostly American, contemporary photographers like Lewis Baltz and Lee Friedlander. This is why his style has little semblance to his renowned peer in Japanese photography, such Nobuyoshi Araju and Daido Moriyama. While other photographers may prefer human subjects and seek to magnify emotions, Kanemura opts to explore lines and spaces.

“I like going the opposite way. No drama, no romanticism. Just lines and shapes,” he explained.

His most famous works include Concrete Octopus (2017), Sunny Side of Suicide (2010) and Air Blood Black (1999). Each compendium offers a window into reality—bleak, rather incomprehensible and, in Kanemura’s own words, “the ugly truth.”

Hiroko Komatsu—Spiraling in time

Hiroko Komatsu began her professional photography career in 2008. Deeply influenced by Mono-ha, a group of Japanese avant-garde artists, her photographs, all of which carrying a cold and lifeless tone, might appear nebulous to the naked eye. But when it was revealed that her work is a reflection on time, the manner in which time constructs and deconstructs, these abstract forms take shape.

“A photograph doesn’t look the same way twice. People don’t look at an image in the same, exact way. There’s not a similar way to look at any photo in the world. Time goes along a straight line and photography is like stop-motion,” she explained.

Komatsu prefers to do large-scale prints to further the impact of her images on a viewer.

A yin to a yang

Though Kanemura and Komatsu focus on the same subject and have a similar feel to their images, the two photographers have divergent approaches to their work. Kanemura’s photographs appear to allude to the chaos of urbanity and the rigidness of the Japanese lifestyle, while Komatsu has a more detached take on her images, concerning herself with the sea changes that are constantly brought on by time.

Despite their differences, one can posit that both bodies of work intend to highlight the trappings of the modern lifestyle. The two photographers have also formed a habit of working closely together and comparing notes.

“We talk about photography everyday. We go to photo exhibitions and then we discuss what we saw. It comes so naturally,” the two mused, talking in succession.

A picture is worth a thousand words indeed and perhaps a few thousands more can be conveyed after spending the day with these two.