May 5, 2022

Mothers in Management: Cynthia Usui

The hardships of rejoining the Japanese workforce for stay-at-home-moms

Company country manager. Supermarket cashier. Author. Mother. Many have used these words to define Cynthia Usui, and in the same breath, judge her. Cynthia Usui has built a reputation in Japanese media for climbing the career ladder in hyperspeed after dedicating 17 years of her life to raising her daughter. Despite limited job choices, a void on her resume and a huge statistical disadvantage compared to her male counterparts, she now runs three establishments as LOF Hotels’ country manager and has written three books in Japanese on her experiences. Her works comprise of “Eight Things Full-time Housewives Should Do Before Getting a Job,” a memoir on raising her daughter and “You Can Decide Your Own Life.”

Usui’s no-nonsense approach says that if you want to be a stay-at-home mom, do it. If you want to pursue your career, do it. And, if you want to be both in your lifetime, do it. “What I’ve come to realize is that yes, I can have it all, but I don’t have to have it all at the same time.”

In these books, she guides mothers back onto the proverbial horse with her straight-talking advice. “Saying that we should choose to work on things that we have passion for is a statement of a very entitled person,” Usui tells Metropolis. “Not all of us are lucky enough to be able to earn a living with what we like to do.”

“In my book, I’m the complete opposite. You need to look at your potential; and at the same time, you need to look at your limitations. If you want a job in the U.S. but can’t even speak English, how can you even think about it without learning English first? The number one limitation is we all have 24 hours in a day. Just being brilliant doesn’t give you an additional 24 hours. So, what do you do with your 24 hours?”

In the past, Usui has run hospitality courses for stay-at-home mothers to build up and develop their skills while out of the workforce and is committed to hiring the same group in her role as a country manager. It was one of her stipulations when she accepted the job.

What I’ve come to realize is that yes, I can have it all, but I don’t have to have it all at the same time.

“I actively hire housewives and single mothers. Instead of just putting up an advert on a job board, I’ll put the word out in these particular communities. I negotiated for 100% authority on being able to hire the people I work with. What female leader would give up half of their potential income to get full power over HR? That’s why I say I walk the talk,” she laughs. “I’m getting things done because I was able to give up something to get what I want.”

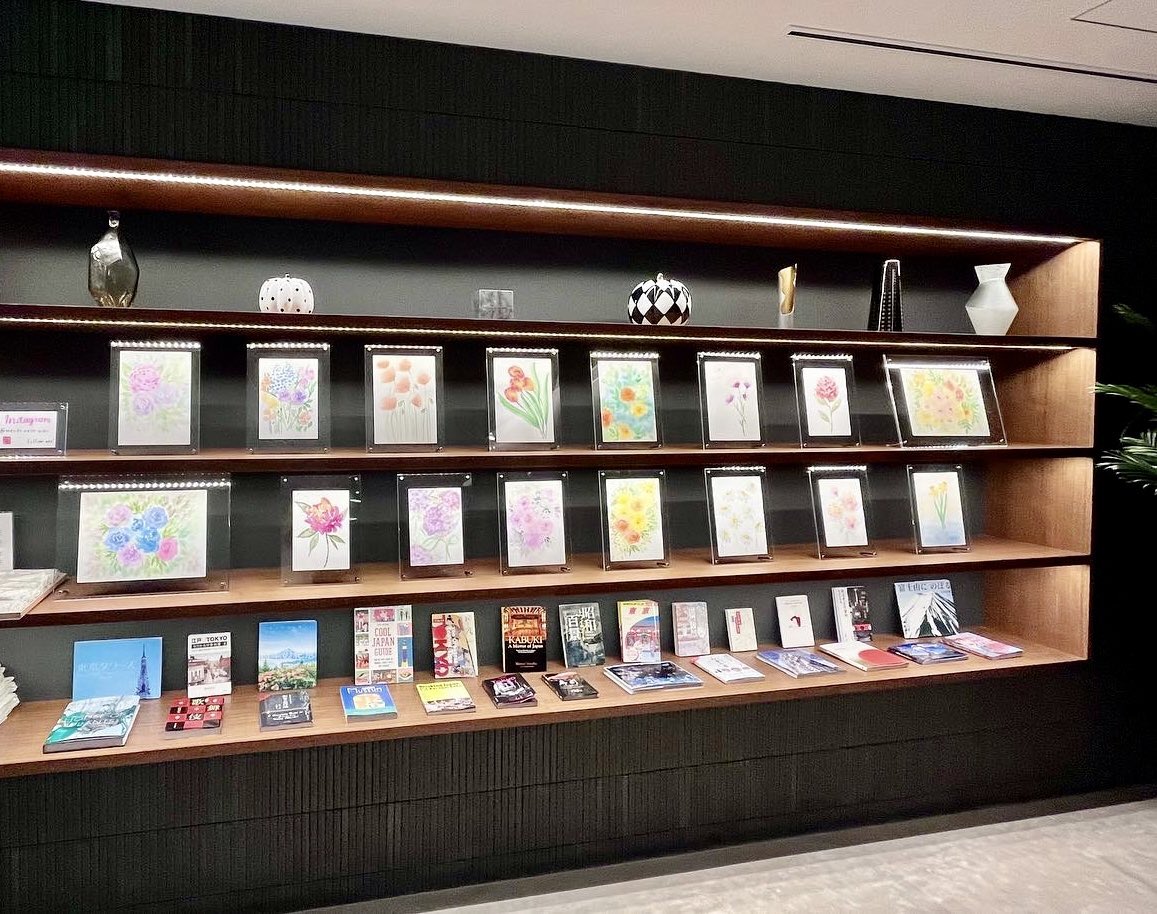

Change comes from the top. With less than 10% of women in Japan holding managerial positions and a dismal place on the 2021 Global Gender Gap Report, we need more women like Usui pushing for power. As well as hiring struggling mothers who need a boost, she also uses the lobby of LOF Hotel Shimbashi as a free exhibition space for female artists. “People gave me the opportunity, and that’s why I’m where I am right now. I believe in paying it forward.”

Apart from job hunting, there are other hurdles that women, and even fathers, need to overcome when leaving or returning to work after their child’s birth. The term matahara, meaning maternity harassment, has been a widespread problem in Japan for many years, with unprecedented cases of power harassment, abuse and torment by coworkers.

Usui reflects on the never-ending pendulum swing of Japanese public thought on mothers, and how she was treated during the 17 years she spent at home. “In those days, the women who continued working were judged as bad mothers. I was the norm: somebody who got married, had children and became a stay-at-home mom. Then suddenly things changed. It was the women who were working and raising their children simultaneously who became the ‘capable women,’ and all those women who stayed home were suddenly the ‘useless women.’ Forgive the word, but what kind of crap is that? You’re sort of judging women and then you go all the other way and judge another group of women.”

These judgments, unexpected daycare closures due to the pandemic, and the balancing act of working and child-rearing has sent many mothers into a “mummy guilt” epidemic. A survey conducted by Nikkei Womenomics Project found that 75% of working women suffer from this affliction, despite spending more time on housework than their male partners. Why, then, is it chiefly a female phenomenon?

“There’s no term for ‘working father.’ We have the term ‘mommy track,’ but we don’t have the term ‘daddy track’,” says Usui.

“I don’t think the issue is supporting mothers. I think it’s also not the issue of women going back into society. It’s the issue of fathers needing to go into the homes,” she continues. “We’re doing all we can so women can go back to work. But maybe the solution here is to do all we can so fathers can be more active parents. Why is it all on the women? Why are we forcing all women to juggle work and parenting? Maybe we should scale down the expectations of the men so that they can do parenting as well.”