Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on November 2009

The middle-aged man has been standing for hours in a line that stretches over a block through the streets of Akihabara. What compels him on this, his only day off, is a complete box set of his favorite manga, Kinnikuman, which costs ¥105,000 and comes with special extras for the first 100 buyers.

This phenomenon is called otonagai, literally “adult buying,” the practice of wealthy otaku hobbyists and collectors purchasing expensive goods. These enthusiasts often buy multiple copies of an item based solely on its cover, and then, instead of opening it, simply display it or stash it away. In 2007, Yano Research estimated the otaku market was around ¥360 billion annually, and at the same time, the market share represented by kids is shrinking. As anime, manga and videogames increasingly target grown men, some question if adults aren’t becoming children.

“Otaku are a slightly strange breed of consumer,” says Takuro Morinaga, 52, a professor of economics at Dokkyo University. “They aren’t really sensitive about pricing. If it is something they want, they will pay any price, no matter how absurd it may be.”

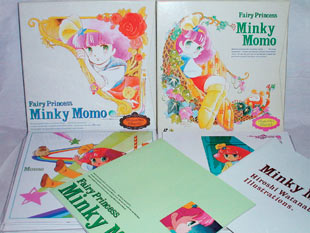

The tradition of marketing to otaku has had a major impact on the evolution of Japan’s contents industry. Take, for instance, “magical girl anime,” which was originally created for young girls but has become the bread and butter of male otaku. In 1979, Hideo Azuma, a manga-ka specializing in both shojo and pornographic comics, released Cybele, the first example of lolicon media. Soon after, otaku started looking for lolicon idols in shojo anime, and studios began pandering to them in the hopes of increasing sales.

The sexualization of little girls isn’t new. Indeed, even the grand daddy of anime, Osamu Tezuka, took his turn with Marvelous Melmo (1971-1972), which concerned a 9-year-old girl who instantly becomes adult size when she eats magic candy. Of course, her clothes are the wrong size—skin-tight children’s wear on a buxom adult woman—which started the popular anime convention of panchira, or panty shots.

But Tezuka meant Melmo to be preliminary sex education for kids, not a show for otaku. Anime like Momo and others which followed in the ’80s were more explicit, and after the collapse of the Bubble, as the number of children and consumers shrank, anime studios looked for new markets. One result was that the sentai superhero team idea for boys was adapted for girls in Sailor Moon (1992-1997)—otaku were lured in by young girls who transform into beautiful soldiers in sailor-suit uniforms.

The massive male fandom became infamous when, at a Sailor Moon stage event that attracted both kids and otaku, an overly eager adult fan made a child cry. Aya Hisakawa, the mild-mannered voice actor who performed the character of Sailor Mercury, attempted to diffuse the situation by calling this fan an ookii o-tomodachi, or “big friend.” The euphemism is still used, along with the implication that otaku are adult children.

Mandrake and Liberty shops both serve collectors; otonagai sightings are frequent.

Mandrake: 3-11-12 Soto-Kanda, Chiyoda-ku. Tel: 03-3252-7007. Open daily noon-10pm. Nearest stn: Akihabara. www.mandarake.co.jp

Liberty has 13 shops in Akihabara; see www.liberty-shop.co.jp for details (Japanese).