“Poet in concrete,” “critical regionalist,” “urban guerilla”: these are just a few ways that the Japanese master architect Tadao Ando has been described over his long career, by journalists, art historians and himself. Entirely self-taught, Ando is perhaps best known for his visionary complexes across Naoshima, the renowned “art island” in the Seto Inland Sea. With the current exhibition, “Tadao Ando: Endeavors,” at The National Art Center, Tokyo, he may soon be remembered for a lot more.

Ando’s material of choice is concrete, a substance crucial to his craft since he started his first practice in 1969. For a material characterised by its oppressiveness and strength, Ando has an incredible capacity to infuse it with a lightness of touch. His style merges complex, often entangled forms, with a sense of soul and simplicity, emphasising empty spaces and ultimately, nothingness. Intrinsic to this style is his integration of buildings with their natural environments. As a result, his buildings provoke reflection, a sense of stillness and calm—almost as if walking through a shrine, temple or church. It’s a feeling I felt strongly while wandering around his awe-inspiring sites in Naoshima, and again while strolling through the NACT’s exhibition halls in Japan’s capital.

Originally hailing from Osaka, Ando is no stranger to Tokyo. His buildings here include Omotesando Hills, Shibuya’s Kaneko House and 21_21 Design Sight in Roppongi. And it was Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel which caught Ando’s eye when he was a teenager visiting the city that inspired him to become an architect. At that point, the young Ando was training to become a boxer, but a few years later this training was abandoned as he swapped his dreams of boxing with night classes in drawing and interior design. By 1968, Tadao Ando Architects and Associates was established, and the following year he penned his first architectural manifesto: “Urban Guerilla Dwellings,” which centered on a tiny, standalone house in Sumiyoshi row, Osaka.

But to call Ando’s oeuvre purely urban would be a fallacy. His works and his buildings do feel like works of art — a feeling reinforced through their current contextualization within an art gallery. They also spellbindingly circumvent categorization, blending dense industrial forms with serenity, combining light and shadow, old and new. The value he places on natural forms and natural surroundings is paramount, strongly highlighted in the exhibition at NACT. The exhibit includes a dedicated section on his work at Naoshima, where his architecture, the sea and the island integrate to almost celestial proportions. But it also reviews recent and upcoming ecological and environmentally-driven projects, such as his current one in the Tokyo Bay area.

This encompassing exhibition leads visitors through an overview of Ando’s creative career, from his early life in Osaka and his first smattering of projects there, to the growth of his international prowess across Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Shown through drawings, models and sketches, the show is split into six sections: “Origins/Houses,” “Light,” “Void Spaces,” “Reading the Site,” “Building upon what exists, creating that which does not exist,” and “Nurturing.” Each section carefully tracks the architect’s successes, alongside beautiful photographs and large-scale installations.

The dedicated section on Naoshima appears in “Reading the Site,” where visitors can learn more about his work on the island and his projects there — Benesse House, Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum and the ANDO MUSEUM — through an immersive installation. Here, Ando’s central belief is felt, that “building-making = environment making.” You may find yourself swiftly booking Shinkansen tickets to the art islands after leaving the gallery.

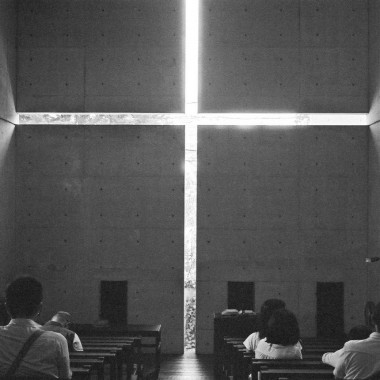

The power of Ando is that his work feels effortless — even religious buildings feel understated, while still being monumental. Ando carried out several religious projects in Japan in the 1980s, including the Church on the Water at Tomamu (1988) and the Church of the Light in Osaka (1989). Light, water and concrete mingle in these spaces, together symbolising another key value of Ando’s — “yohaku,” or “void spaces” where people can come together. This sense of community is felt in the outdoor exhibition hall, where his “Light Church” from Osaka is reproduced in full-scale.

Ando’s lightness of touch is felt throughout this fascinating exhibition, which, much like Ando, manages to be awe-inspiring without going over the top. On the one hand, seeing his buildings in-situ is more aligned with Ando’s core architectural beliefs. But learning, through this exhibit, more about the architect and his inspirations, his projects beyond Naoshima and his focus on the environment, feels important at a time when people feel less connected to the spaces they occupy. Artfully highlighting the infinite potential of Ando’s architecture and interconnected spaces, it’s clear that boxing’s loss is undoubtedly architecture’s gain.