The Noto Peninsula was once considered the edge of the world. For centuries, Japan’s rulers banished unruly lords to the rugged, windswept cape. Today, Noto retains that feeling of undisturbed isolation — cut off from the hubbub of Japan’s more popular locales.

Being cheap and wanting an adventure, I explored Noto on my commuter bike. I paid for my passage with sunburn and soreness. In return, I saw a side of Japan that had previously been little more than a blur outside the shinkansen window.

My route followed a “つ” shape around Noto’s south, east and north coasts. I rode a mamachari, or “mother’s chariot,” so named for the bike’s capacity to haul anything from groceries to infants. Mamachari are slow, hulking bikes, seldom used for long trips. So, while I barrelled down Noto’s hills like a bowling ball, most of the coastline was travelled at a lesiurely pace, the perfect speed to soak in all that Noto had to offer— you just had to know where to look.

On my second day, I trundled toward Gunkan Jima, or “Battleship Rock.” The island features on practically every one of Noto’s brochures—and for good reason. A sight to behold at sunrise, it rises from the sea like a great imposing mushroom.

Next to Gunkan Jima is Matchmakers Beach. Here, couples can ring the deafening “Bell of Everlasting Love.” After I’d soaked in a nearby onsen (and received an enthusiastic tour of the century-old building by its owner), I camped in Gunkan Jima’s shadow. The bell rang all night.

In 2021, Japan’s central government granted Noto ¥800 million ($7.31 million) in an effort to help the region recover from the pandemic. During my trip, I saw evidence of this subsidy everywhere; from the shiny new Bell of Everlasting Love to the new signage directing my route.

Infamously, Noto spent a large amount of this new money on “Squid King” — a 13-meter-long fiberglass squid parked by the roadside in Tsukumo. The town was once a hub of squid production but had since been mostly abandoned—a familiar tale in rural Japan. To Squid King’s many critics, His Majesty was a frivolous waste of a much-needed handout. Outlets from the New York Times to the BBC reported on the controversy.

When I rolled through, Tsukumo was overtaken by what can best be described as squid-mania. Throngs of tourists packed every shop. Grandparents nibbled dried squid, couples flaunted matching squid t-shirts, and kids screamed for squid balloons. A recent report found that Squid King netted Tsukumo 22 times his original cost in the last year alone. Clearly, the exposure served the town well.

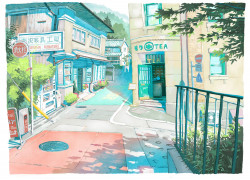

For decades now the peninsula, like much of rural Japan, has experienced a demographic decline. The evidence is everywhere, from aging homes to empty villages, but the local governments are finding creative ways to revitalize their areas and cultural scenes. On my third night, I camped outside an abandoned school that had been renovated into a museum.

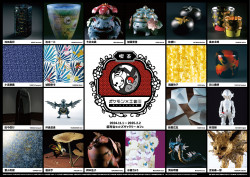

The Suzu Theater Museum turns Noto’s gloomy statistics into something hopeful, if not beautiful, by reworking evidence of this decline into works of art. Carefully arranged by local artists, the exhibits display everyday items found within Noto’s many vacant homes. Arrayed across the walls was family porcelain with no one left to inherit it. Home movies and clips of the sea played on vintage televisions — their owners having long departed.

The experience was melancholy. Yet, it was also inspiring, for it showed a community’s determination to preserve and share the memories of those who had once called Noto home. It’s representative of the peninsula’s knack for adapting its past and present into something you’re glad you took the time to enjoy.

A culinary example of this quality can be found in the salt farms on Noto’s north coast, which I rode through on my fourth day. These farms use a method of salt production called agehama, a centuries-old technique that requires over ten years’ training to master. The Samurai lords of present-day Kanazawa coveted this salt for its unique taste. Today, the nearby Sio cafe uses it to make pancakes. Light, fluffy and inexplicably crunchy; they were delicious.

On my fourth and final night, I camped in Wajima, a town on Noto’s north cape famous for its millennia-old crafts industry and weekend market. Sore and full of grilled fish, I soothed my sunburn in the sea beneath a lighthouse.

The Noto Peninsula is a timeless place, not only for the way its attractions interweave past and present, but also for how it has been neglected. Mostly due to geography, the region missed out on much of the prosperity, glitz and amenities enjoyed throughout Japan’s cities. As a consequence, Noto hasn’t changed much from a time when life’s pace was more relaxed. After the electric pace of Tokyo, this change was refreshing.

I chose to ride my mamachari around Noto because, for such a famously slow-paced region, it made sense to travel slowly. Most guides will tell you that renting a car is the best way to see the Noto Peninsula. I disagree. Though Noto’s countryside may be quiet, there are treasures to be found in the backwoods. If you’re whizzing past behind the wheel of a car, you might miss them.

By taking my time on this long commute, I hoped to come across the sights, stories and quirks that make Japan’s countryside a mystery to uncover. Floating in the Sea of Japan off Wajima, the lights of horizon-bound squid boats indistinguishable from the stars, I felt as though I had.