It is difficult to imagine what Tokyo looked like before the 1964 Summer Olympics. Beyond bestowing the credential of first Asian host city, the ‘64 Games were a catalyst for radical urban development in Tokyo, changing not only the face of the city but its fundamental character. “An entire city, it seemed, was transformed—10,000 new buildings. It was dramatic,” says Robert Whiting in a recent interview with Metropolis. Whiting is an author and journalist who has written extensively on Japanese sports culture and the ‘64 Games.

When explaining this urban revival, the first development anyone points to, including Whiting, is Tokyo’s infrastructure. The Shinkansen, a transportation innovation that linked Japan’s distant commercial centers, broke ground as part of the Olympic development plans. So did the Haneda Airport monorail and the Metropolitan Expressway system, the network of roadways that to this day weaves between high-rises and stands elevated over the city’s major thoroughfares. Alongside these massive infrastructure projects was the germination of real estate developments throughout the city, ushering in a boom era in concrete architecture.

While it would be easy to stop the list there, the effect of the ‘64 Games was so much more than a hard hat fad. “In the late ‘50s, Tokyo was rat-infested. You couldn’t drink the water; 40% of the Japanese had tapeworms. There were no ambulances and infant mortality was 20 times what it is today,” explains Whiting. “Moreover, narcotics use was endemic and it was considered too dangerous to walk in public parks at night. Yakuza numbers were at an all-time high.” The pre-Olympic Tokyo Whiting describes will feel foreign to any long-term resident of the city, as it should. The ‘64 Tokyo Olympics jump-started the decades-long process of molding this city, one still healing from the scars of firebombing raids and occupation, into an international capital. While it would be naïve to see the Olympics as the sole factor in resolving Tokyo’s former ills or a solution without consequences, it is difficult to overestimate its historical impact. Whiting doesn’t mince his words: “Some people call it the greatest urban transformation in the history of the world.”

With the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics nearly wrapped, international eyes are focused firmly on Japan and organizations hosting the Tokyo games are buckling down on preparations. Ballooning construction in Nihonbashi, Shibuya Station’s maze of white walls, the Tokyo Tower observatory and Meiji Jingu Shrine renovations — it’s no coincidence if you’ve noticed a swell in scaffolding and jackhammering over the last year or two. 2020 has its own redevelopment plans firmly laid out with the promise of another round of Olympic-related construction projects. But in the details, what will the Olympic Games repeat mean for Tokyo? Is the city looking at another surge in urban revitalization or will it be closer to a superficial facelift?

♦♦♦

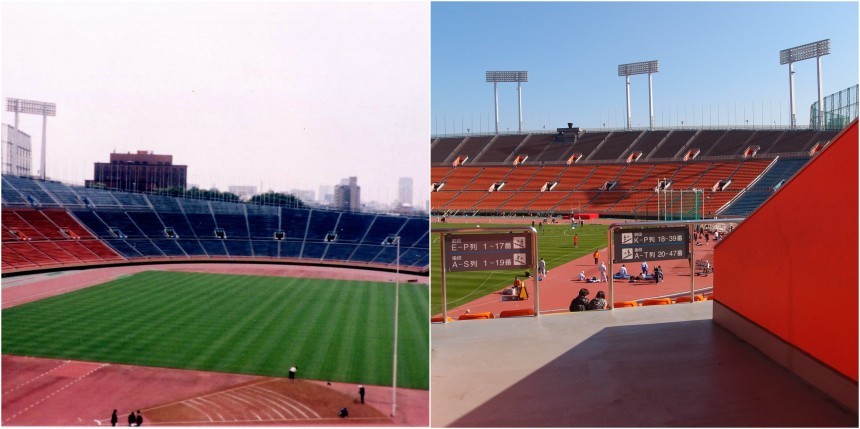

Nothing has made more headlines in the lead-up to 2020 Games than the new National Stadium. The planned reconstruction of the 1964 original, located on the northwest edge of Meiji Jingu Gaien Park, was mired in bad press from the planning phase. Zaha Hadid’s original design was criticized by many in the Japanese architecture community when it was announced in 2012. Due to an untenable budget, it was eventually scrapped. When respected Japanese architect Kengo Kuma’s replacement designs were selected in late 2015, the hope was a course correction for the stadium. His architectural firm, Kengo Kuma & Associates, took over construction through a joint venture with the Taisei Corporation and Azusa. Kuma spoke to Metropolis about his design philosophy for the stadium in a glass-walled conference room on the rooftop of KKAA’s offices. Their Gaienmae location is just blocks away from the new National Stadium building site, which he visits every few days for materials inspections and to see his designs materialize.

Kuma has tremendous respect for the project at hand. He grew up swimming in the National Gymnasium’s Olympic-sized swimming pool and remembers the moment he looked up to see its sweeping roof — a study in concrete elegance — as one that confirmed his love of architecture. Renowned architect Kenzo Tange designed that Olympic stadium. It was built alongside a stretch of greenery used for the ‘64 Olympic Village, known today as Yoyogi Park. These Olympic projects no doubt bolstered the nearby commercial and cultural hubs of Shibuya, Omotesando and Harajuku, turning them into the neighborhoods we know today. But Tange’s stadium did not just physically change Tokyo’s urban landscape, it was held as a symbol of a new Japanese era. If Kenzo Tange’s National Gymnasium was a bold pronouncement of Japan’s industrialism, then Kuma says he’s looking to lead an organic Japanese post-industrialism.

Wood. This natural material has been the center point of Kuma’s career and aesthetic, which adopts small, bare strips of wood to craft detailed facades and striking interiors. Some of his previous work, including the Asakusa Culture and Tourism Center and the Nezu Museum in Minami-Aoyama, heavily feature this material, as well as bamboo. Wood is once again on display in his National Stadium design. When asked what impact he wants this project to have on Tokyo’s urban design, he explains that the city direly needs a reintroduction of natural materials.

It’s important to remember that Tokyo was once a city of single-story wood frame houses, a landscape that was largely erased during WWII and the postwar construction boom. Wood for the new stadium will be sourced from all 47 prefectures and cut to mimic the dimensions used to build a traditional Japanese home. But beyond the historical significance of wood in Japanese architecture, Kuma says forests hold a spiritual place in Japanese culture. Shinto shrines are often built at the edge of woodlands to mark an entrance into spiritual territory. In a country that is nearly 70% forest, wood becomes both a vital element and a practical material.

While Kuma was once inspired by the work of Kenzo Tange, he sees his own buildings in conflict with this school of architecture. The ‘64 Games solidified concrete as the building material of Tokyo. Kuma wants his wood-based designs to bring sustainable and organic architecture to the forefront of Tokyo’s post-2020 era. His mission to bring natural beauty back to the city center inspired a National Stadium design that would incorporate Meiji Jingu Gaien’s greenery. With the top half of the stadium walls built at an angle, the trees below the structure will continue to grow, enveloping the building in its natural landscape. Many of Tokyo’s once-lively waterways were filled with cement or contaminated during the ‘64 preparations, including the Shibuya River, which ran through Meiji Jingu Gaien. As a gesture to this history, Kuma plans to resurface a portion of the river and build a small creek on the stadium grounds.

While Kuma has done his best to reinvent the 2020 National Stadium, like its ‘64 predecessor, the project has taken a toll on the Shinjuku district surrounding the stadium. The original stadium prompted the demolition of a large number of homes in the once-quiet Kasumigaoka and Sendagaya residential areas. For 2020, the same neighborhood has lost the Toei Kasumigaoka Apartments, a public housing complex supporting 231 households. The Showa-era complex was demolished last year in order to clear space for the expanded stadium. Completed in 1961, it was constructed, in part, to house those originally displaced by the Olympics. Reuters reported that one older resident of the complex would be moved a second time for the Tokyo Olympic Games, having already lost his childhood home.

An official from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government explained that the relocation of the households was a necessity and they attempted to implement alternative housing. “In addition to the newly built Jingumae 2-chome apartment located in the vicinity, we secured a number of alternative metropolitan housing opportunities and implemented relief sessions and individual consultations with the residents … We also pay relocation expenses.” As with the ‘64 National Stadium, the incident, on a smaller scale, shows the cost of Olympic projects on select Tokyo residents. It also represents Tokyo’s constant cycle of urban revitalization, clearing older pockets of land — whether a yokocho (traditional alleyway) or a Showa-era home — to realize new versions of the city.

♦♦♦

While the new National Stadium project has already broken ground in Shinjuku, it’s just one building in a much a larger redevelopment campaign by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. There are other major neighborhoods in the 23 wards poised for a revamp. Shibuya, Ikebukuro and Nihonbashi have all seen large-scale construction projects related to the Olympic Games. A new station on the Yamanote Line, located partway between the current Shinagawa Station and Tamachi Station, is planned, with Kengo Kuma & Associates at the design helm. The reality of the ‘64 Games was that many construction efforts led directly to urban renewal and gentrification. In 2018, however, urban sprawl has pushed residences to the edges of Tokyo. With redevelopment happening in more central commercial areas, this large-scale relocation has actually been minimized.

Although displacement may not be endemic to the entire 2020 Olympic project, there are certain populations that have suffered. In the last year, construction sites have swallowed up many of the public spaces long occupied by Tokyo’s homeless population. Construction has left the homeless torn from their communities and normal places of rest. The eviction of homeless from Shibuya’s Miyashita Park last year saw vocal protests from anti-Olympic activists who decried the forced removal of Tokyoites from public property. These evictions happened on a smaller scale at the new National Stadium site in Meiji Jingu Gaien Park. An official from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government said, “Public park administrators certainly consider the human rights of the homeless who live in the park. We provide consultation on daily living and introduce homeless populations to the welfare department if necessary.” While the homeless have faced the brunt of Olympic construction plans, many new high-rise residences are emerging from similar projects.

Since the majority of new stadiums are planned to be built in Chuo-ku and Koto-ku, 2020 will give life to residential districts in the Tokyo Bay Area. The Olympic Village, for example, is set to open on Harumi Island facing the water and the Rainbow Bridge. An official from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government explained there are plans in place to convert the village apartments into residential buildings following the Games through a partnership with private contractors. Kuma predicts the projects’ impact on the Bay Area will be on par with Skytree in Oshiage — reimaging an industrial district into a residential area infused with new neighborhood shops and culture. While the reclaimed land of Tokyo Bay has until now largely avoided residential development, the Olympics seems to have set in motion a new Bay Area real estate bubble.

According to Whiting, the projects surrounding the 2020 games are scratches on the surface compared to the scale of the 1964 Olympics Games. However, there is reason to pay attention. “What’s going on now is not inconsequential. A lot of people haven’t really taken notice, but there is an entire new city that has gone up around Tokyo Bay. I live in Toyosu and see it every day.” As Tokyo continues to expand eastward and redevelops central neighborhoods, new cultural hubs will emerge, like Shibuya and Harajuku once did. Others may fade. The bay, in its own way a remnant of Tokyo’s industrial past, is one district on this path towards reconstruction and reinvention. “The view from the Rainbow Bridge of the Tokyo nightscape is one of the most beautiful in the world,” says Whiting. “Most people living overseas don’t know it exists. Tourists think of Tokyo in terms of the Ginza and Meiji Shrine. After 2020, that will change.”