October 29, 2009

Vice Guy

An American journalist’s new book exposes the seedy underbelly of Tokyo

By Metropolis

That night I called my source and repeated everything Kaneko had said to me.

“Very interesting,” he said. “I’ll personally look into this. My guess is that someone in his own organization is trying to take The Cat down. Ten to one it’s a power struggle.”

“What does he mean by saying that he has a good working relationship with the cops?”

“Ahh, that. Let me explain. Part of being a yakuza cop is being assigned to Anti–Organized Crime Division 1, which gathers information on the yakuza: How many offices do they have? How many members? Who’s in the organization and who’s not? For the yakuza cops, the fastest way to get the answers is to go to the yakuza and ask. The Cat is a crafty old guy, so he won’t come right out and tell you. He’ll just leave the materials lying around the office, and we’ll just offhandedly read them while he’s on the phone. Sometimes he’ll leave them in the garbage can so we can ‘steal’ them. He never hands them over.”

“Why would he do that?”

“Because it’s the way things work. He keeps the cops happy so we don’t have to find an excuse to raid the office to get the intel we need. It works out well.”

“Why don’t you just tap his phones?”

“This isn’t America, and we aren’t the FBI. We couldn’t get permission to run a wiretap. It just doesn’t happen.”

“You don’t think he’s bribing somebody?”

“If he was, he wouldn’t be stupid enough to get caught doing it. He’s the smartest yakuza in the organization. I’ll find out what’s going on and get back to you.”

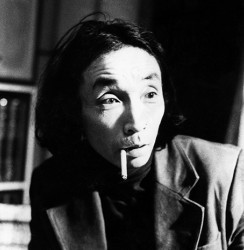

The author speaking with the Vice-Captain of the Omiya Police Department in 1993. On their first meeting, he was mistaken for an Iranian escaped from a holding cell and almost jailed.

Two days later, he called me with the goods. The rumor was being spread by one Yoshinori Saito, the number four guy in the Sumiyoshi-kai. Saito had told one of the detectives in Section 1 that Kaneko was bribing a cop. Saito hadn’t named the cop, thus sending the police into a feeding frenzy while they tried to find the mole.

That was on the cop side. On the yakuza side, Kaneko and Saito had long been at odds with each other. Lately, Saito had wanted to sell speed to the convoy of truck drivers who made their way through Saitama, but Kaneko didn’t want any part of it. Kaneko’s boss, Nakamura, had allegedly been a meth head in his youth, and Kaneko didn’t want his boss getting involved in a business that might tempt him to return to bad habits. Saito had deliberately spread the rumor, knowing that it would result, through a certain convoluted logic, in making the organization think The Cat was a police stoolie. Saito didn’t have the guts to challenge The Cat himself. He was going to let the organization take care of it.

“So what do you think I should do with this information?”

“Tell it to Kaneko. As soon as possible.”

Reluctantly I agreed to communicate the situation to Kaneko. I called his office and scheduled an appointment for that night.

It was freezing cold, which didn’t help because I was already getting the shivers. Besides, yakuza offices are spooky enough in broad daylight. Before I could even knock on the door, Kaneko opened it and gestured me inside. He was wearing jeans and a dark green sweater. He looked like a yachting instructor.

I sat down on the sofa, and this time I drank the tea. I told The Cat everything I knew.

He nodded as I spoke, closing his eyes, fingers spread out on the table. “Thank you. I now understand. I owe you for this,” he said.

“Maybe it’s not my place to say this,” I dared, rather like a fool, “but rather than having to deal with this crap, why don’t you just leave the organization?”

The Cat opened his eyes and took a deep breath. “Look at me. If I dress like this, I look like any other businessman on the train on his day off. But if I roll up my sleeves”—which he then began to do—“that’s the end of the pretty picture.” From his wrists, extending up his arms as far as I could see, were gaudy, elaborately engraved tattoos. You couldn’t see a vestige of bare skin.

“I’m long past forty, and I’ve branded myself for life. I’ve got no education, no diploma. I don’t have social security or health insurance. I have money in the bank, and I have this organization. Where could I go? If I run, the Sumiyoshi-kai will hunt me down and kill me because they’ll think I’ve turned into a dog for the cops. If I stay, I have a chance to survive. It’s not much of a life, but I’m not ready to throw it away. So I’ll deal with this problem.”

I thanked him for the tea and got ready to leave. He put his hand on my shoulder and looked me in the eyes.

“You’ve saved my life. I don’t forget these things. If there’s anything you need—information, women, money—come talk to me. There are some debts that are never repayable. I’ll owe you until I die.”

“I didn’t really do much.”

“It’s not how much you do that counts, it’s what you get done.”

“Then what I’d like is information. I don’t want it if it has strings attached, though. I don’t ever want to owe a yakuza.”

“That’s not a problem. But I’ll tell you now: I will share information with you on what other yakuza groups are up to, but not our own. Our business remains our business. You can ask questions and I won’t lie to you, but if it involves us I’ll tell you I won’t discuss it. Is that understood?”

“Understood.”

“You sure you don’t need any pussy?”

“No, I’m okay.”

“Is it because you like boys?”

“Not that I’m aware of.”

“Well, then, all right.” He walked me to the door and shook my hand.

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan, by Jake Adelstein (Pantheon Books, 352pp, $26). Available at bookstores throughout the city, Amazon US

Two weeks later the Saitama police were once again drinking green tea at The Cat’s office. I never asked what had happened to Saito; Kaneko and I never discussed the incident again.

From that point, Kaneko and I carried on a very businesslike relationship. I’d drop by for tea every couple weeks, and I’d always call in advance. He’d give me some leads on a couple of stories, we’d chat about the predations of yakuza life versus that of reporter life, and then we’d go our separate ways. He’d always try to fix me up with a hot Japanese woman, and I’d always decline.

Having The Cat on my side was a huge plus as a reporter. Of course, I had reservations about taking his information. I was sure that sooner or later he would lean on me for a favor; but he never did. I also wondered if taking information from a man who was, by his own admission, an antisocial lawbreaker was morally defensible. I suppose that’s all part of Informant 101, but still I had qualms. Eventually, I came to understand the lesson that had been told to me from the beginning: information is neither good nor evil; information is what information is. The people providing the information have their reasons and motives, many of them impure. What matters is the purity of the information, not the person.

Thanks to The Cat, at one point in time, I knew when a gang war was breaking out between yakuza factions before the police did. It helped me stay on the ball. He was the best source a crime reporter could ask for, since it’s always better to have one great source than a hundred lousy ones.