April 1, 2022

What is Japanese Literature?

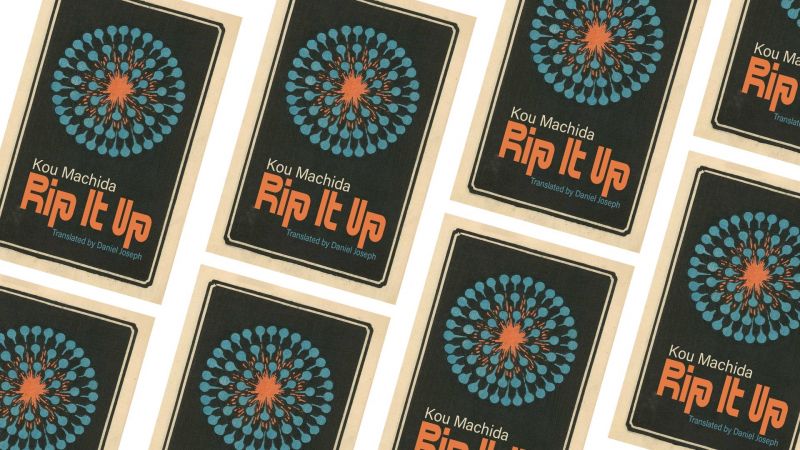

Studying Rip It Up by Kou Machida (Translated by Daniel Joseph)

By Iain Maloney

What is Japanese literature? I’ve been worrying about this question for a while now, but it came to a head shortly before I quietly slipped away from a Japanese literature Facebook group. Ostensibly formed to host discussions, give recommendations and share rumors about forthcoming releases, the group quickly became an unpleasant place to hang out. Unusual for Facebook, I know.

The reason for this was an overzealous administrator who took it upon himself to define exactly what Japanese literature is. Or, more accurately, what it isn’t. His argument boiled down to “book X doesn’t match my image of what Japanese literature is; and therefore it doesn’t belong in this group.” Much of this revolved, inevitably, around race, birthplace and nationality. Is Li Kotomi’s work Japanese literature? Yu Miri’s? Kazuo Ishiguro’s? Lafcadio Hearn’s? But more importantly, why does it matter?

I’m from Scotland, a small country that takes its literature seriously. Much of Scotland prides itself on being inclusive, mainly because we are too small to be exclusive. Scots are defined as anyone who chooses Scotland. Scottish literature, therefore, is any writer who is from Scotland, lives in Scotland, or writes about Scotland. A mischievous article by Professor Willy Maley suggested that this includes George Orwell and Virginia Woolf, since “1984” was written in Scotland, and “To The Lighthouses” is set there. Whatever the merits of this, I raise it because I think the intention is laudable. The drive is one of inclusion, not exclusion. Open doors, open arms.

The question bothers me because it’s my job to write about Japanese literature, and that should really mean I know what Japanese literature is, and I don’t, not in any definable way, just the same as there’s no way I could define Scottish literature even though I contribute to it through my books. The problem is that once you begin to define something, you are also defining what it isn’t; you are building fences.

“In the minds of some people outside Japan, there’s a sense that Japanese literature is supposed to be elegant, mysterious, stately, refined—all that orientalist wabi-sabi bullshit that gets laid on Japan in general,” says Daniel Joseph, translator of the recently published “Rip it Up” by Kou Machida. In Japan, Machida’s books have been an acknowledged influence on writers like Mieko Kawakami and Hiroko Oyamada.

But, when his book “Kiregire” (“Rip it Up”) was translated, publishers wouldn’t touch it. Not because it wasn’t good, but because it is so outside the mainstream expectation of what a translated novel from Japan looks like. It took Inpatient, a small press with nothing to lose, to take the chance.

“The idea that the entire literary output of a nation should fall into certain narrow categories is inane,” adds Joseph. “The idea that Japanese literature can’t be bawdy, funny, earthy, ridiculous, absurd, over-the-top can only hold us all back. But one of the amazing things about Machida is that the literary establishment inside Japan had the same reaction to him. They had internalized this uptight idea of Japanese literature and were scandalized by him.”

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: readers like that Facebook mod only read Japanese books that fit into their definition of Japanese literature, so publishers, regardless of personal desire, are forced to follow sales and so they only publish only books that fit this mold. Currently, this means a plethora of books with a cat somewhere in the title (“The Traveling Cat Chronicles,” “The Cat Who Saved Books,” “The Guest Cat,” “If Cats Disappeared from the World,” etc.). It’s gotten to such a ridiculous level that Alison Watts, translator of the forthcoming “The Boy and the Dog” by Shusei Hase could joke, “look out cats — your day is over!”

The guiding principle now is Amazon’s algorithm: “People who bought X also bought Y.” If you read books by Haruki Murakami, it will recommend more books by Murakami, and books that are Murakami adjacent. As you read these, the feedback loop intensifies. Publishers take notice that readers are reading Murakami; therefore we need to publish more writers like Murakami. Find me the next Murakami.

“The Murakami brand was so wildly successful that he defined Japanese literature for the foreign market for decades,” says Joseph. “We’re finally coming out of that now, with people like Hiroko Oyamada, Mieko Kawakami and Aoko Matsuda, though a lot of books are still riding the Murakami train—the same simple style, very slightly transgressive but basically safe.”

Machida is anything but safe, and reviewers elsewhere have described the narrator as vile, a monster, as the embodiment of toxic masculinity, something I don’t disagree with. “I think another reason publishers were a little averse to this book is that we live in a time where people seem to have a hard time with the concept of narrative voice,” says Joseph. “A character says something vile or misogynist, therefore the author is a vile misogynist. So I understand why publishers are cagey about a book like this, with such a jerk as a narrator. Publishers are afraid of seeming reactionary, even if the work is satirical.”

Which is understandable. The wider point, however, is that if readers of Japanese literature in English are to get as full a picture as possible of what Japanese literature is, then important, influential writers like Machida need to be published and read as much as the Murakami-adjacent ones, and the stories about cats.

This is why I don’t understand that Facebook mod: If we love Japanese literature, then surely we want to read as far and as widely as possible? We want to explore those nooks and crannies, not close them off. So rather than defining exactly what we think Japanese literature is and railroading publishers into feeding the algorithms, we need to banish exclusive attitudes that are killing the chances of us discovering our next favorite Japanese author. Try something new, challenge your taste buds, embrace growth. Open your borders.