July 10, 2025

What’s the Difference Between Soju and Shochu? And Sake?

Differences, similarities, and why these East Asian spirits are trending

What’s the difference between soju and shochu? Soju and shochu may sound alike, but is that just a coincidence? And what about sake, arguably the best-known East Asian alcoholic drink?

Soju has been taking the world by storm. Did you know that Jinro Soju is the best-selling spirit brand in the world? Meanwhile, shochu is experiencing a resurgence, gaining attention from mixologists worldwide and rising in popularity as izakaya culture continues to spread globally. But

But how exactly do these two drinks differ, and what makes them similar?

Advertisement

Shared Origin and Etymology: Soju and Shochu

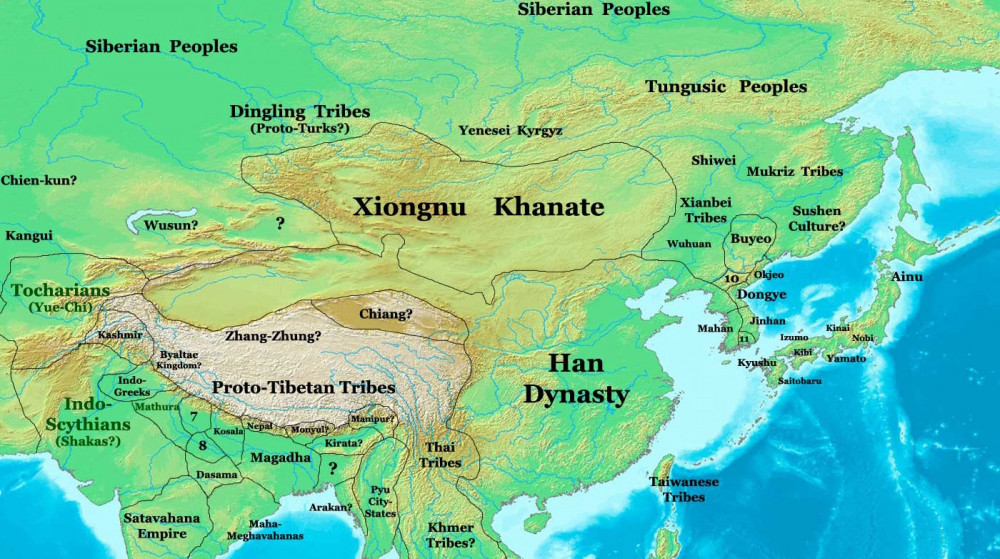

Both soju and shochu trace their roots to the Chinese term shaojiu (燒酒), meaning “cooked alcoholic drink,” a reference to distilled spirits. This Chinese liquor, now commonly referred to as “baijiu,” has roots in the Neolithic period, with systematic distillation processes emerging during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD).

Historically, each version was regarded as an equivalent of the other: soju in Japan was often thought of as “shochu from Korea,” and likewise, shochu was considered “soju from Japan” in Korea. In short, at least historically, soju and shochu are essentially the same spirits with shared origin and etymology. Though they differ slightly in characteristics and tendencies, they are primarily distinguished by their origins.

Ingredients and Alcohol Content

Both spirits can be made from various base ingredients, including rice, barley, and sweet potatoes. However, Japanese shochu can also be made from brown sugar, especially in Kyushu, adding a unique depth to its flavor. Traditionally, soju was primarily made from rice, but many well-known brands today, especially popular fruit-flavored soju, are mass-produced using cassava.

The Korean Peninsula was under Japanese control from 1905 to 1945. Immediately after, the region was divided between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, leaving the nation with poverty and a severe rice shortage as the population grew. From 1965 to 1990, the South Korean government banned the use of rice in soju production, a policy that has influenced the ingredient sourcing to this day.

Traditionally, both soju and shochu had a wide range of alcohol content. However, government regulations have since standardized their typical alcohol levels. Soju typically has an alcohol by volume (ABV) ranging from 12.5% to 53%. Most varieties found in supermarkets are around 20%. Shochu generally sits at 25% ABV, though it can reach as high as 45%. Both are considered mid-level alcohols, offering versatility for drinking straight or mixing into cocktails.

Distinctions in Production

Soju is often distilled multiple times to achieve a neutral, smooth flavor, making it comparable to vodka. Premium soju brands often highlight their extensive filtration processes, such as using bamboo charcoal, as a key selling point. This clean taste serves as a versatile base, which has contributed to the popularity of fruit-flavored soju varieties.

Today, most soju in South Korea is mass-produced by a few major companies due to the country’s economic landscape and chaebol culture. Many modern soju brands use ethanol distilled to 95% ABV. It is then diluted with water and mixed with sweeteners and flavorings. The latter is especially for the popular fruit-flavored varieties. However, traditional varieties like Andong soju still exist. There’s a growing movement toward artisanal soju, crafted in historically preserved ways.

Shochu is divided into two distinct classifications in Japan. The first type, honkaku shochu, meaning “authentic shochu”, is produced through single distillation and is highly regulated in both ingredients and production. Known for its savory and bold flavors is generally considered a high-end variety.

The second type, korui shochu, is made through consecutive distillation, similar to soju. This type of shochu has a clean, neutral taste and is affordable, making it a popular base for liqueurs like umeshu (plum wine). Okinawan liquor Awamori, made using long-grain indica rice, is technically classified as korui shochu under licensing laws. However, as an indigenous Ryukyuan alcohol, it is widely recognized as a distinct category.

You might also enjoy: The 9 Best Japanese Whiskies for Gifting.

Advertisement

What’s the Difference Between Soju and Shochu? And Sake?

Many online articles that compare soju and shochu are titles like “Soju vs. Shochu vs. Sake”. And if you have read the article up to this point, you should know this is weird. (Hint: sake is not distilled). The English name “rice wine” already explains that it is not a spirit—though, to be precise, sake is much closer to beer in its production. So, at first glance, soju and shochu are worth comparing, while sake seems irrelevant here.

However, sake and shochu share something in common: koji (Aspergillus), a type of mold also used in fermenting soy sauce and miso. Yellow koji (A. oryzae) was traditionally used for both sake and shochu. In 1901, University of Tokyo scholar Tamaki Inui isolated and cultivated black koji (A. luchuensis), now used in some shochu and awamori. Then, in 1918, Genichiro Kawachi, the father of modern shochu, isolated and cultivated white koji (A. kawachii), now used in shochu.

Soju traditionally relied on nuruk. This is a fermentation starter similar to koji, along with makgeolli, but this is uncommon in mass-produced soju found in supermarkets today. While many big brands use the ethanol method, some incorporate white koji from Japan, while others use traditional nuruk.

Fun Fact: “Korean Shochu” in Japan

Kyogetsu is a “Korean Shochu” brand widely recognized in Japan. It entered the market before soju gained global prominence and was marketed as shochu. Called “Gyeongwol” in Korean, it is still produced in South Korea near Mt. Seorak, but is now almost exclusively sold in Japan.

Today, Kyogetsu is often associated with the sunakku scene—a retro Showa-era cultural staple. Sunakku establishments are small bars with a counter. They’re typically run by a “mama,” an older woman who entertains customers with conversation.

Kyogetsu, unlike the small bottles of soju that are standard today, is packaged in larger bottles. This fits well with the Japanese “bottle-keep” culture. This is especially popular in sunakku, where patrons buy bottles and store unfinished portions at bars for future visits.

Today, soju is a very popular spirit in Japan, available virtually everywhere, including convenience stores. While “soju” has become a common term, it typically refers to the modern Korean standard 350ml bottle. Interestingly, even with the widespread popularity of the term, Kyogetsu is not usually referred to as “soju” but is considered a type of shochu instead.

Advertisement

Embracing Both Spirits

Both spirits share many similarities, but their unique histories, cultural contexts, and regulations have shaped them into distinct drinks. Soju, now produced through modern methods, has gained global popularity. But there’s a growing movement to return to its traditional production techniques. On the other hand, while shochu hasn’t been a staple among Japan’s younger generation, is gaining recognition worldwide for its craftsmanship.