November 13, 2020

America’s Tokyo

Revisiting the capital 75 years after the American Occupation began

In November of 1945, when LIFE published a series of sketches as its first look at Tokyo under American occupation, the magazine’s writer noted that the artist, Bernard Pelin, “found two dominant forms of struggle” in the Japanese capital. “The Japanese were struggling to find a roof for their heads and a morsel for their mouths,” the unnamed writer lamented. Given the trials that Japan faced following over a decade of total war, this was an unsurprising caricature penned by a foreign correspondent. And yet, the American GIs, the victors, the occupiers and the enforcers of an American-flavored democracy imposed from above, also struggled, or so the writer mused: “GIs were struggling to find souvenirs which prove to the folks back home that they had been to Japan.”

For many an American GI, as for American civilians and other non-Japanese people, Tokyo, from September of 1945, transformed from an enemy capital to a home. But more than that, it emerged as a city of American comforts, sexual pleasure and leisure.

LIFE, perhaps unknowingly, illustrated the American service members’ imagination of Occupation-era Tokyo: a city of pleasure, a Disneyfied space, ripe with exotic objects, sites and people. For many an American GI, as for American civilians and other non-Japanese people, Tokyo, from September of 1945, transformed from an enemy capital to a home. But more than that, it emerged as a city of American comforts, sexual pleasure and leisure. Never mind that American planes had blanketed the city in firebombs over the previous years, killing upwards of 100,000 thousand people and reducing neighborhoods across the capital to nothing more than rubble.

“Compared to most other national capitals,” wrote Helen Mears in The New Yorker in November 1946, “Tokyo is a comfortable place for an American to be these days, but it is also at least for a civilian newcomer from the states a confusing one.” Confusing, yes, for as she notes, the linguistic differences alone perturbed many new arrivals. Yet the city was “comfortable” in that it was wrapped in a coating of Americana with English-language signage, American wares and housing complexes that transposed the milieu of America into the heart of Japan. Is this so different from the view and experiences of first-time American tourists — or, as has been pointed out, expatriates — in the capital?

Take, for example, my first time in Tokyo, when I was a tourist and not a resident. I was taken with the apparent comforts and ease of travel within the city, but more than that, I was overcome with a subtle and ineffable similarity between Tokyo and my home of New York. This extended beyond the ubiquity of American brands and products to English signage, menus and conversation.

And yet, the history was all hidden, because I visited these sites without any idea of my country’s influence, unaware that my comfort in these spaces had emanated, in part, from the colonial exercise of occupation many decades earlier.

I was also uninformed of the city’s history, unaware that a visit to Yoyogi Park, for instance, was a visit to the site of not only a former Imperial Army parade ground and Olympic Village, but to the former home of an American military complex called Washington Heights. Omotesando, as Harajuku, with trendy stores and youth culture, developed much of its current character in the 1950s onwards, as the site adjacent to this American military complex. And yet, the history was all hidden, because I visited these sites without any idea of my country’s influence, unaware that my comfort in these spaces had emanated, in part, from the colonial exercise of occupation many decades earlier.

The contemporary American tourists’ idea of Tokyo, though neither singular nor homogeneous, thus mirrors the imagination of the American in the occupation, which began 75 years ago and concluded seven years later. Think less of essentializations of Tokyo as a city of either anime lovers — the world of Akihabara — or salarymen. Rather, the continuity rests more in the notion of the city as viewed, by American tourists, through a colonial gaze, of certain perceived freedoms, of entitlement and, on some occasions, ignorance. The storied historian of Japan, Harry Harootunian, has written of what he calls “America’s Japan,” an American domination of the Japanese voice, as opposed to “Japan’s Japan.” For Harootunian, the origins of this stretch back to the inception of the relationship in the mid-1800s, only to be reaffirmed during the occupation.

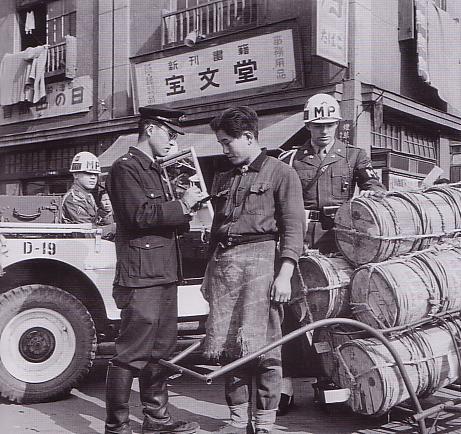

Take souvenir hunting, that trivial, though essential part of travel for most tourists. In “Tokyo, Fall of 1945,” an English and Japanese photo book published by Bunka-sha in 1945 and sold to those in Tokyo, including American GIs, there is a photograph of a service member in Ginza. The American, in uniform and with glasses, holds bags and boxes of “purezento,” or “miyage mono,” as the caption reads. A photograph of a souvenir stall of fans and musical instruments, also in Ginza, compliments the GI-cum-shopper. Ginza served as the home of Western goods since the late 1800s, something that morphed into an American hub during the occupation and a contemporary shopping and tourist hub in the present.

Finally, one may ask why write this piece now, in a moment when tourists, including those from America, cannot enter Japan due to the coronavirus pandemic? This moment, a brief and traumatic respite from tourism in Japan, as elsewhere, offers a chance for alteration, for those in Tokyo to reimagine and reconstruct how foreign tourists consume the capital. It may be months, if not longer, before American tourists begin to revisit Tokyo and, when they do return, they might discover a changed city.