With awe-inspiring designs that defy convention, Taro Yaguchi has transformed the traditional art of origami. From enormous 3D shoes to suspended illusions of cars and even a two-meter-long cruise ship, his creations push the boundaries of this traditional craft.

Yaguchi established the very first origami studio in Brooklyn over 12 years ago. Now, with his visionary spirit undeterred, he has brought his talents to Tokyo—unveiling a new studio location nestled in the eclectic community of Asakusa, that promises to be a haven of creative expression.

However, Yaguchi’s mission extends beyond making revolutionary origami figures. With a passion for teaching, he aims to spread the joy of this art form through his origami activities and workshops. Within the walls of Taro’s Origami Studio, the artist unveils the craftsmanship behind every fold, inviting students to embark on this journey of creativity.

In an interview with Metropolis, origami master Taro Yaguchi guides us through his studio—a world where the ordinary becomes extraordinary and the art of folding paper transcends its ancient origins.

Metropolis: What inspired your love for origami and why did you decide to open an origami studio?

Yaguchi: I loved origami as a child and I think all children love origami; but in Japan there aren’t any career opportunities there, so naturally I stopped practicing it.

When I was living in the U.S., I realized that origami was very popular and there were people who had a genuine interest, but no place to pursue it. There are many Japanese people living in the States that might visit cherry blossom festivals where there’s an origami booth, but there are no places to follow up. So, I wanted to expand the opportunity for people to practice origami.

About 10 years ago, I was featured by NHK’s program ‘Passion USA’ about the origami book I had created ‘Origami Cars, Trucks, and Trains,’ and the final question the interviewer asked me was, “What is passion?” In response, I said that I had a dream to open an origami studio in the States. Multiple viewers contacted me directly after the broadcast, asking me to open a studio in their city. One of them invited me to Brooklyn, and so I had no idea that I would actually be able to open a studio but it ended up happening. I found that origami naturally found its place in the Brooklyn arts community.

M: Your original studio is in Brooklyn, New York. Why did you decide to open a new location in Tokyo?

Y: After the Brooklyn studio, it was a dream of mine to open a location in my home country; I knew I eventually wanted to expand to Tokyo. Asakusa is a popular area for tourists and there are many independent art stores around. You can find a lot of traditional Japanese craft shops here, like specialty leather stores.

There are lots of people in the very center of Asakusa, but we didn’t want to be in an incredibly busy location. I enjoy speaking with each customer and having a quiet, serene atmosphere in the studio. There are lots of tourists who like to drop in to take a break from all of the sightseeing and walking in Asakusa. It’s nice to step out from the crowded parts of the area and do something hands-on to unwind.

M: How did you start making such adventurous origami models?

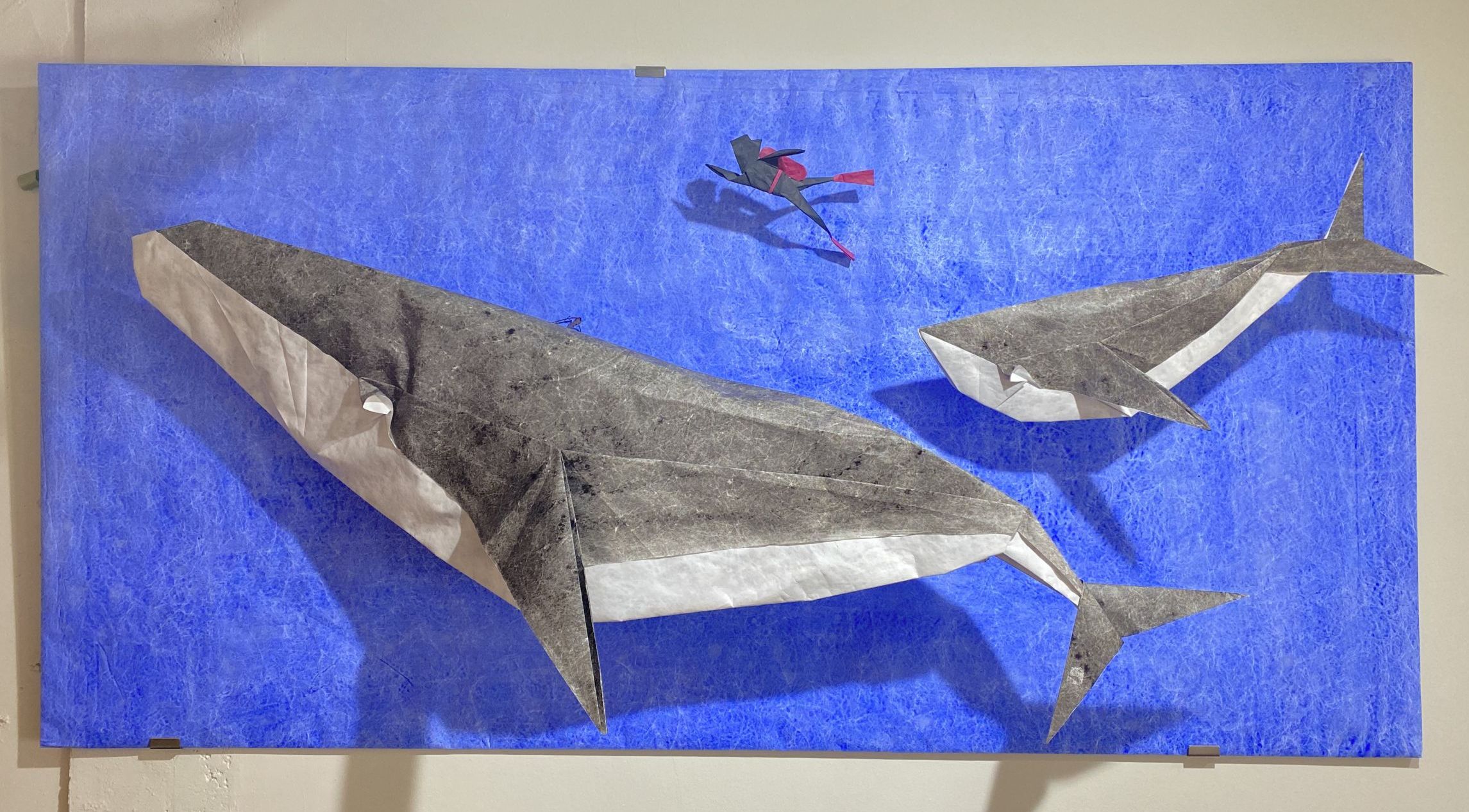

Y: You never see origami in a museum, but I wanted to make it something that could be seen as art. My book on 3D origami models of transportation was my first step towards creating unconventional origami. I never see people making the same kinds of things as me, like a 1.2m long whale, a realistic cherry blossom tree, a school of koi fish.

Once I created the studio, companies started contacting us because they thought that origami could complement their brand. Even though I started my studio focusing on teaching origami, we gradually became more well-known and got to make some interesting things for companies and brands.

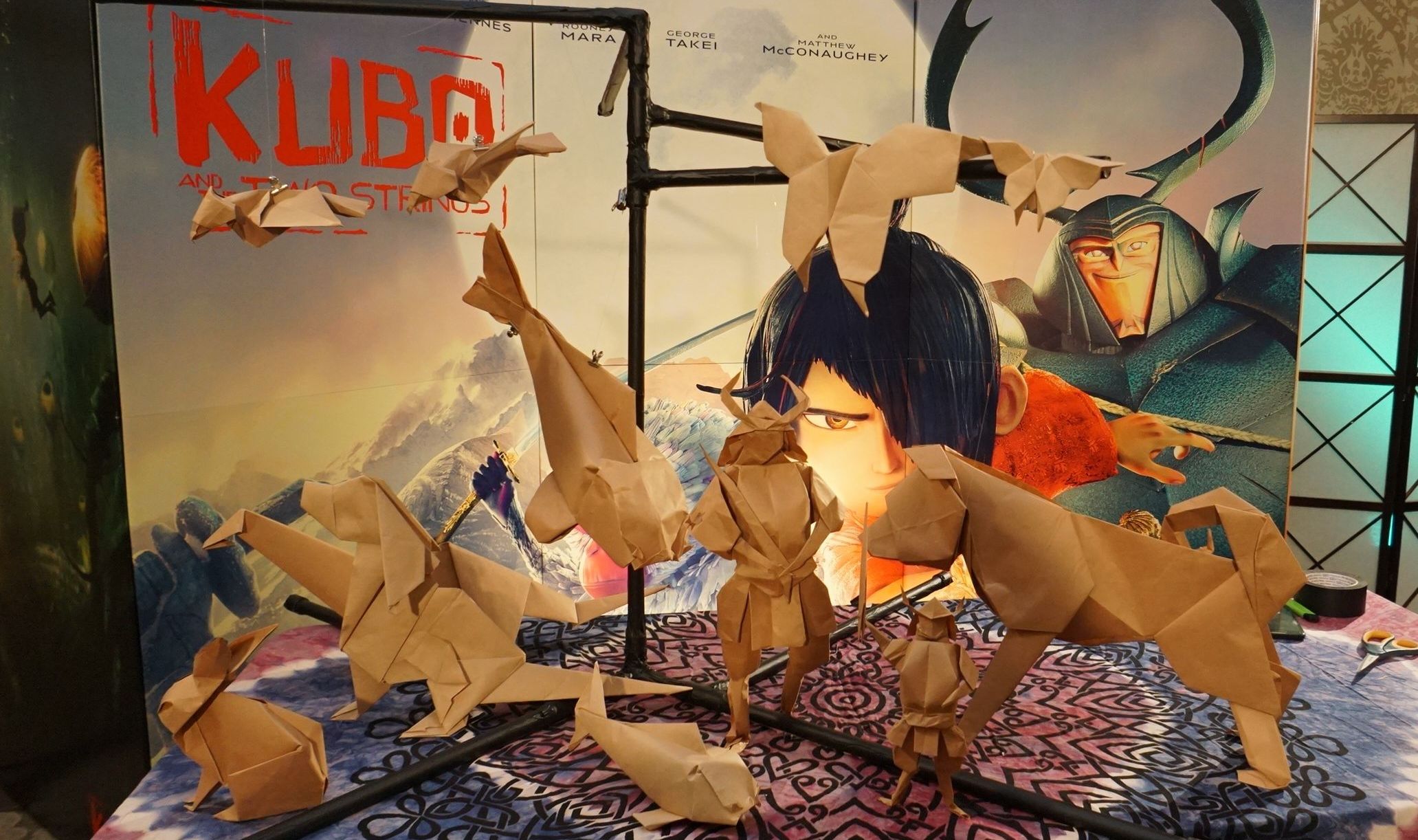

One that comes to mind was a project we did for the stop-motion film “Kubo and the Two Strings” where we were hired to create origami models, like the iconic samurai characters. I even had a chance to speak with Charlize Theron and Matthew McConaughey about origami at the opening night for the film.

M: I understand you also previously started your own patent law firm. Origami is very different from law, but what are some things that you think about when creating your own business?

Y: I started with creating original 3D origami designs, but from my experience if you want to start your own business, there is a gap between the invention and commercialization of that product.

In order to fill that gap, I needed to elevate origami into something that could be a viable business. The technique I used to do that was to make it ‘pop’. Similarly to the way that manga is not a part of Japanese culture, but rather Japanese sub-culture, I had an idea to market origami as a sub-culture to make it more modern and exciting.

M: As someone with a background in mechanical engineering, how do you tackle some of the more challenging designs?

Y: Western clients, because they have less knowledge about origami, tend to think we are able to make anything. We get quite a lot of challenging propositions from companies, so there is a lot of problem solving involved in the process.

One of our clients, Simon Malls (from Simon Property Group), said that they wanted giant 3D origami sneakers and high-heels to put on display at their mall for a year. We usually start with a rendering of the model on a software program during the design process. It’s very difficult to make a large origami model and maintain its shape because large paper is much heavier, so I developed my own technique using thin plastic sheets instead. The design process involves using some technology and some trial and error.

M: In Tokyo, it must be more difficult to establish yourselves as an origami studio because origami is more widely available here. What sets your studio apart?

Y: Our studio is quite unique and there really aren’t any paper craft stores that offer what we do. In our studio, you can come in at any time to fold origami and we have activities running every day throughout the week. Lots of tourists enjoy coming in because our staff members speak English and our origami activities are easy to grasp.

People sometimes come in and show me photos of their pets that I can fold for them on the spot. I really enjoy doing these kinds of live origami demonstrations and creating something that is very sentimental for customers.

M: Your origami studio’s activities use your own, original kyu-level learning system. What inspired you to create this system, and how do you believe it improves upon traditional methods of teaching origami?

Y: Origami can be thought of in many different ways, but I think it’s primarily a technique that you can master—like martial arts. Many people ask me how many origami models I can fold and my genuine answer is, anything.

There are basic folds that you need to master in order to create more complex models. That’s what sets origami apart from other paper crafts. You have to make 10 models, or 100 models in order to master the technique.

The original method tells you to fold at each step, but you don’t know what you’re making until you reach the final folds. In our system, we teach the purpose and name of each fold. For example, in a ‘cabinet fold’ you have to fold the paper in half first so that you have a center line to create symmetry. Understanding each fold is the key to grasping the basics of origami and once you have the right tools, you can really make anything.

Our origami folding method is actually used in our certification program, where anyone can learn how to master the craft of origami and eventually collaborate with us on some of our larger projects.

M: Many people find that they feel quite calm when practicing origami. Would you say that origami brings peace to people?

Y: People say that when they are doing origami, they don’t need to focus too much on the steps and are quite relaxed when letting their hands fold from memory. I have found that children with ADHD really enjoy origami; I have a friend’s son who is always running around, but when he does origami he stays in one place.

People are always too busy, especially people in Tokyo; they don’t have a lot of time to do activities for leisure and most people end up playing computer games, but origami is much better for your brain. Origami helps people slow down and take a break from their busy lives.

M: Why was origami in particular a craft that you wanted to spread to represent Japanese culture in the US?

Y: Origami is very important for Japanese people. When former president Barack Obama came to Hiroshima, he folded two origami cranes that are still displayed there. Japanese people continue to be amazed by those cranes because it shows an understanding and appreciation of our culture. I also think that Japanese craftsmanship is considered so valuable, partly thanks to the regular practice of origami in our childhoods.

I started my origami studio in the US and it was very important for me to be a Japanese person opening that studio to share my culture in a way that was authentic and personal.

M: Have you noticed any differences in how people in the US and people in Japan approach origami?

Y: For Japanese people, origami is an ordinary part of the culture, so fewer people see it as anything other than a hobby for children or an activity to do during a festival. It was quite a difficult path for me to take, but I truly believe that there is a market for origami in Japan.

From my experience, westerners enjoy origami because it’s so new to them. For example, we were hired by ANA Intercontinental Hotel to create mini origami figures for their front desk, lobby, and rooms; they mentioned to me that international guests were more excited about seeing origami in their hotel rooms than expensive wine.

M: Your studio offers a wide range of origami-related activities, from birthday parties to work team-building events. What is it about origami that makes it so versatile?

Y: Origami has so many different facets as it can be considered an art, toy, form of education, healing, hobby, etc., so it is relevant in many ways. It is kind to the environment, inexpensive, and readily available for anyone. My next dream is to visit a refugee camp to entertain kids with origami; my thought process is that with 100 sheets of paper, you can entertain and bring joy to 100 children.

M: Origami has existed for around 1,000 years as an important part of Japanese culture. How do you balance preserving the traditional aspects of an art form while also expanding it in new, creative ways?

Y: I started with the ‘subculture’ direction of origami, designing my own models and publishing my origami books, but ultimately came back to origami as a part of ‘culture’ as I technically teach traditional origami in my studio.

I think I am always changing my direction and challenging myself—I recently became interested in incorporating more traditional aspects of origami in my own designs. There are only 3 washi stores still located in Japan, designated as UNESCO World Heritage sites, and they are unfortunately a dying business. Washi is a traditional Japanese paper that has a very unique texture and consists of long fibers that weave together. It’s not very popular for origami because it’s difficult to fold with, but I found that it can be great to use with more complex designs as it is really strong and doesn’t break or fall apart when used with water.

I began with wanting to modernize origami, came back to traditional origami, and then decided to explore even deeper into the traditional craft— doing something unique as an origami artist and playing more with that contrast between traditional and new.

For more information about Taro’s Origami Studio and their origami activities: tarosorigami.com