Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on January 2014

Not every big exhibition of Impressionist art in Japan has to originate from a famous foreign museum. The current show at the National Museum of Western Art is sourced almost entirely from the NMWA’s own collection and that of the Pola Museum in Hakone.

“Monet: An Eye for Landscapes” brings together dozens of the master impressionist’s canvases as well as many works by other artists from before, during and after Monet—including Gustave Courbet, Camille Pissarro and Vincent van Gogh.

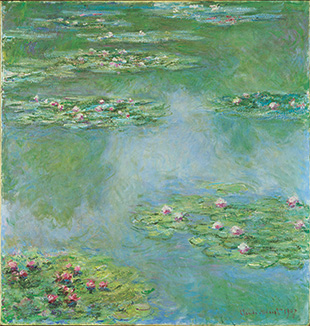

What’s most noticeable is the change between early Impressionism and its later period. In the public mind it seems to be closely tied to its most famous painters, especially Monet and Renoir, and tends to be defined by their more popular works. For Japanese audiences, the works Monet did later in life, when he retired to his house and garden in Giverny and concentrated on painting his lily pond with its Japanese bridge, figure large.

But this stereotypical image is really just one chapter of the story. In its early days, Impressionism was a wide-ranging rejection of artistic conventions that limited ‘respectable’ artists to a narrow range of themes and styles—historic or mythological subject matter painted in a suitably grand way.

Most importantly Impressionism was an embrace of modernity, an obsession with all that was new, modern and proletarian. Only later did Monet and Renoir push it deeply into “biscuit tin” territory.

This is clear at this exhibition, where early works by Monet and other impressionists show many signs of the modern world. Monet’s The Goods Train (1872) not only shows a steam train with its plume of smoke cutting across the picture plane, but the background is a forest of factory chimneys.

Steam trains and chimneys are almost signature features of these works, cropping up in several canvases. This is partly because the person whose collection formed the basis of the NMWA, Kojiro Matsukata, was particularly interested in industrial paintings—although his favorite artist was the Anglo-Welsh painter Frank Brangwyn, whose enhanced realism was far from Impressionism.

Monet must have realized that modernity, with its telegraph poles, railway bridges and precise, engineered lines, didn’t suit his brush. His dappled brushstrokes were much more adept at depicting leaves and waves.

Also, the later Monet travelled much less. A photo of the artist shows him in old age, looking content, portly and a little lazy. At this stage of his career he was focusing on the narrower range of subjects that were provided by his garden.

This escape from modernity into a personal comfort zone was also something of a wider trend, reflected in symbolist and poetic painting popular at the end of the century, like the pseudo-religious iconography of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes Poor Fisherman (1887-1892) or the work of Odilon Redon.

Some of these paintings don’t seem to bear too closely on Monet and raise suspicions of the curators trying to throw everything they could into the show. But this is nevertheless an effective and stimulating look at the work of the painter regarded as the greatest of the Impressionists.

National Museum of Western Art until March 9. See details.