March 6, 2021

Japan’s Lost Tradition of Wild Food

'Eating Wild Japan' tracks the culture of foraged foods with a guide to plants and recipes

Have you ever heard of fuki (butterbur), tochi no mi (horse chestnuts), warabi (bracken root), kajime (seaweed) or kihada (amur cork)? These are just some of the obscure foods that have lost the battle to the prettier, plastic-wrapped vegetables of Japan’s supermarket shelves today. But we are reintroduced to these native delights, which were once staple foods in ancient Japan, in the new book “Eating Wild Japan: Tracking the Culture of Foraged Foods, with a Guide to Plants and Recipes” by Winifred Bird.

In ancient Japan, the population’s diet was much more varied and deeply rooted (apologies for the pun) to the land. It was often based on hunting and gathering of sansai (wild mountain vegetables), which are grown naturally by Mother Nature. Once, sansai were “just food,” but today, they have become a symbol of a tradition that is, unfortunately, being practiced by fewer and fewer members of rural communities.

Sansai appears in literature as far as “Manyoshu,” a collection of Japanese classic poetry dating back to the Nara Period (AD 710–794), used as a metaphor for the seasons. Guides and almanacs on how to pick and cook the “vegetables of the mountains” began circulating in the early 1700s.

After the development and spread of agriculture, sansai’s role dramatically changed and became associated with poverty, eaten only out of necessity by peasants. Ironically, they simultaneously became a symbol of luxury among the rich as they had to be procured from the wild and so were considered more adventurous and exciting than basic field crops.

Today, the abundance of food and our busy city lifestyles don’t require us to forage sansai in the wild anymore. Nonetheless, contemporary Japanese sansai are a rare delicacy reminiscent of ancient times.

Essays on wild foods

Bird has spent years wandering around the mountainous areas and coastal lines of Japan. Her process of rediscovering old cultures and traditional ways of eating brings her in contact with old take no ko (bamboo shoot) masters, sansai enthusiasts, energetic mountain villagers, cordial professors and seaweed foragers who guide her.

The book has a strong historical approach, but Bird, as she feeds the reader nutritious geographical and historical information, makes the narration lighter through a collection of diary-like essays about her encounters with sansai.

Illustrated guide to plants and recipes

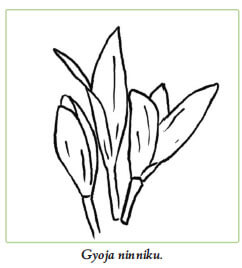

The second part of the book evolves into a manual-like illustrated guide to plants, with a brief description, notes on toxicity, preparation and suggested recipes. The third and last section of “Eating Wild Japan” consists of a collection of recipes that introduces basic Japanese preparation methods.

Climate change, habitat loss and overuse of natural resources are some of the factors that Bird mentions as coexisting causes of the rapid loss of Japan’s wild-plant populations. Urbanization and demographic trends also play an important role: the knowledge about how to pick and prepare sansai remains safeguarded by a core of elderly country people who have no successors and whose wild foods wisdom will soon be lost.“As long as the mountains remain, they will give us food, so we must take good care of them,” said Oikawa, an Ainu woman who works to document and preserve traditional food culture, whom Bird met in south-central Hokkaido.

Book Illustration by Paul Poynter

“Eating Wild Japan” is not only a superbly-written and engaging read but plays an important role in spreading and preserving the knowledge of the Japanese wilderness.

Through her experience as a journalist and her personal interest as a cooking and eating enthusiast, she delivers a product that is perfect for Japan-lovers, complete sansai strangers and expert wild foods connoisseurs. It is a valuable introductory tool in English on the forgotten world of “eating wild” in Japan.

Five Japanese wild foods you have probably never heard of:

-

Fuki

Fuki (butterbur) flower buds are mostly eaten in tempura, or marinated and sautéed. Use the mature leaves to wrap rice and meat –korean-style. Bird describes the taste of fuki as slightly bitter and medicinal.

-

Tochi No Mi

It takes about two weeks to render tochi no mi (horse chestnut) edible. Ash is used to leach the toxins that make them so bitter. In tochi zenzai, the dense and sticky texture and the pungent, bitter taste of the horse chestnut is perfectly balanced by the sweetness of the adzuki beans.

-

Warabi

Starch extracted from the roots of warabi is still used today to make light, jiggly mochi –warabi mochi– which you have likely seen before, usually covered in kinako (roasted soybean) powder. Be aware that the mochi made of bracken root has a very short shelf life. The warabi mochi commonly seen in konbinis and supermarkets is made with potato starch, which is a cheaper substitute of warabi. For a savory dish, try warabi leaves in ohitashi, a light sauce made with dashi.

-

Wakame

Did you know that the Japan Fisheries Agency estimates that over eighty percent of seaweed produced in Japan is farmed? Foraged wakame has a smoother texture and an almost sweet taste. Try wakame shabu shabu to appreciate the flavor at its best.

-

Ginnan

If you’ve been in Japan during the fall, you’re surely familiar with the pungent odor of ginnan – the seeds of Japan’s gingko trees. The almost unbearable smell pervades the streets but once peeled and roasted, ginnan sprinkled with salt become a quick, nutritious snack or an unusual topping for chawanmushi (steamed egg custard).