Amid the towering cypresses, the crystal clear Isuzu River and the serene wooden and thatch-roofed halls, Ise Shrine sits at repose. It’s a rare moment of stasis in the bustling life cycle of Japan’s most sacred shrine, the home of the Sun Goddess.

But repose doesn’t mean silence. Nearly eight million visitors come here to worship every year. The annual kinen-sai, or ceremony to pray for a good harvest, was held this year between February 17-23 alongside traditional dancing that represents the agricultural process, with the hearty musical accompaniment of bamboo flute and drums.

But in two years’ time, the Jingu Shikinen Zoeicho, or Shrine Memorial Construction Management, will launch. This organization will establish the plan setting the course for the next decade: the rebuilding, from complete scratch and using entirely ancient techniques, of 16 shrine buildings and over 1,500 artifacts.

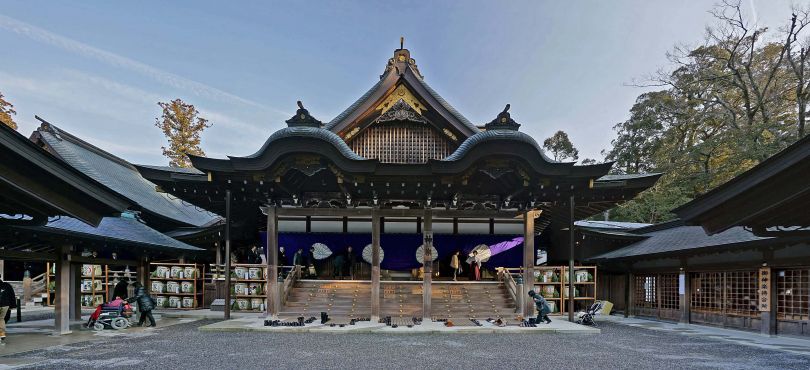

photo by foooomio

Japan’s holiest site, and one of its most ancient traditions, exists in the form of a twenty-year cycle of rebuilding and demolishing. This year marks the half-way point in the cycle after the previous construction in 2013—the perfect time to reflect on the shrine’s remarkable reconstruction and surprising evolution over the last several cycles. The triumphant completion of rebuilding isn’t the only moment that matters. The spiritual concept of cyclical rebirth, the change it inspires in Japanese society, and each rebuilding’s long-lasting effects on the transmission of traditional culture bring further meaning and holiness to the site.

Mythic origins

Located in the southeastern Mie Prefecture, Ise Grand Shrine is a massive 5,500-hectare complex consisting of sacred forests and 125 shrine buildings, most importantly the Inner and Outer Shrines. The Inner Shrine, known as Kotai Jingu, enshrines the most venerated deity in Shinto, Amaterasu Omikami, the Sun Goddess. Amaterasu is believed to be the mythical ancestor of Japan’s imperial lineage. Legend says that 2,000 years ago, the daughter of Emperor Suinin set out in search of a permanent location to worship Amaterasu. She wandered for 20 years until she arrived at Ise and established the Inner Shrine. Historians mark the first shrine building as being erected around 678 BCE, and the first ceremonial rebuild as occurring in 692 BCE. With only a few interruptions in times of war, the shrine has been rebuilt roughly every 20 years since. The standing shrine today is the 62nd rendition.

An epic eight-year journey

While details on the exact schedule for the 63rd rebuilding aren’t yet available, we can look back at the previous rebuilding process, which included over 30 rituals and ceremonies.

Major festivals and ceremonies are held at nearly every step of building the new shrine: the cutting of trees, transportation of timber, praying for the safety of the site, setting the foundational pillars, raising the frames, building the thatch roofs, and purifying the priests and divine artifacts in the new palace. Most importantly, per Ise Shrine PR staff, is the ceremony known as sengyo. “[It’s] the most important part of rituals for moving,” says a representative. “A symbol of the deity is moved to the new palace—and a ritual of offering from his majesty the emperor.”

This constant reconstruction became sustainable due to a forest management plan established by the shrine secretariat during the Taisho Period (1912-1926), creating a semi-permanent supply for all the timber in forests owned by Ise Shrine.

The traditional and rite-infused techniques involved in the rebuilding are a far cry from modern efficiency: it takes four years alone to prepare the timber.

The traditional and rite-infused techniques involved in the rebuilding are a far cry from modern efficiency: it takes four years alone to prepare the timber. Junko Edahiro, who attended many of the ceremonies for the 2013 rebuild, details how logs are soaked in a lumber pond for two years to leach out extraneous oils. The logs are then left outside for a year to acclimatize them to all four seasons. Builders spend another year polishing and covering the logs with Japanese paper. This curing process provides exceptional strength to the timber, which is key to the shrine’s central role of protecting life across all of Japan.

photo by z tanuki

The intensive building process uses entirely traditional techniques, transmitting forms of architecture and culture that would otherwise be lost to time. Logs are held together by carefully carved wooden joinery connections. Specialized iron axes, adzes, chisels, saws; old-fashioned carts, trolleys, and tracks; hand-powered drills, traditional looms for crafting silks and textiles; hand-made forges for crafting ceremonial swords. “The most important technology at Jingu is social,” writes Brian Potter at Scope of Work. “It’s the transfer of skills and techniques from one generation to the next, ensuring the temples and artifacts can continue to be reproduced accurately. The only way to pass it on [the knowledge] is to create the conditions for someone to acquire it.”

The cycle is ultimately sustained through a society that engages with the shrine and its traditions. Marcus Teeuwen, an expert on Shinto at the University of Oslo, says that one of the most significant rituals is the Okihiki festival, the only opportunity for visitors to see the Inner Shrine up close. This involves “not just insiders but also locals and worshippers from the outside,” he explains. “Okihiki is like a town festival, with many school children and parents involved. Sengyo is of course the climax, but only invitees are able to witness it.” Children and the elderly pull timber and white pebbles on beautifully decorated carts in a joyous ritual that still plays a key role in the shrine’s construction.

A cycle still evolves over time

The rebuilding process ensures that Ise is simultaneously old and new. Architects theorize that Japan’s trend among first time homeowners of building a new house rather than buying an old one descends from this original tradition of rebuilding. Each generation witnesses destruction and creation on the level of the private and familial, as well as the sacred and the national. Used timber from the demolished old shrine is distributed to other shrines CYCLES across Japan, so Ise serves as a sort of origin point for sustaining ancient traditions and buildings all over the country.

Architects theorize that Japan’s trend among first-time homeowners of building a new house rather than buying an old one descends from this original tradition of rebuilding.

Maintaining a cycle, however, doesn’t mean that things don’t change. John Breen, professor emeritus at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, explains that over the last four rebuilds, Ise Shrine has experienced a steady process of “de-privatization,” reemerging into the public and political sphere. In the 1990s, Ise priests invested in branding and marketing, and created logos, taglines and large-scale amulet sales. In 2013, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo visited as an active participant escorting Amaterasu to the new shrine, becoming the first post-war minister to participate in Ise rites.

Yet as much as things change, they also stay the same. “Young people, women especially, were conspicuous amongst the nine million who visited Ise in 2013,” writes Breen. “They were drawn to Ise, not on account of its imperial, public aspirations, but for private, personal reasons, much like pilgrims everywhere at all times.”

Before long, the ever-changing cycle, and the fundamental rhythm of Japan’s spirituality, will begin to move again. Until then, amid the towering cypresses, Ise Shrine sits at repose.