August 28, 2025

Traditional Japanese Tea Guide: Beyond Matcha

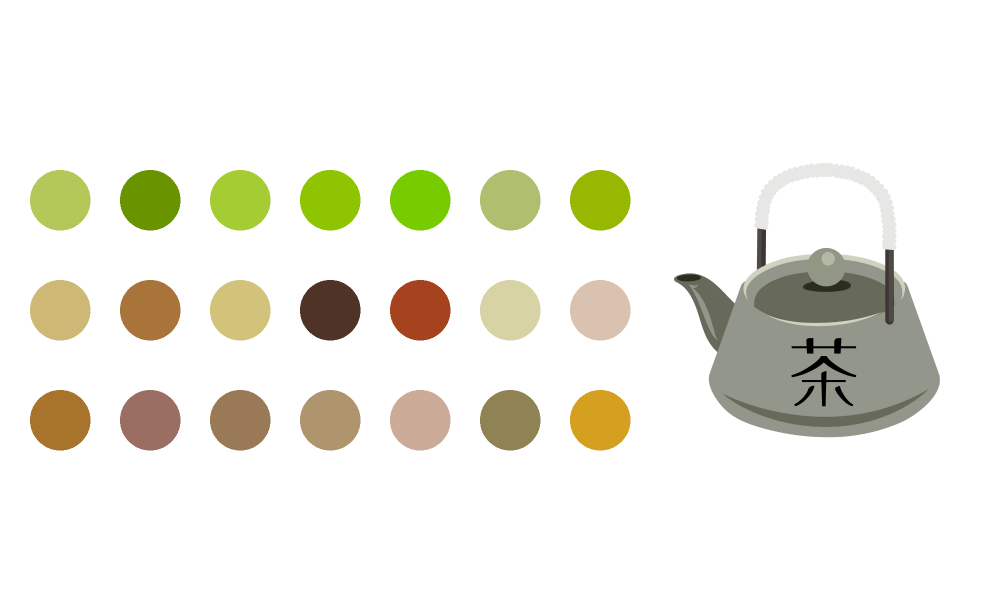

21 types of Japanese tea you should know

By Metropolis

Japan is home to many tea varieties, cultivated for more than a thousand years.

Matcha is perhaps the most recognisable cultural export, once adopted by health gurus and now experiencing a new wave of popularity among Gen-Z (alongside labubu).

Although Japan is most closely associated with green tea, there are many distinct types to explore, as well as Ryukyu varieties rooted in Ryukyuan history and non-green tea options, including various tisanes. Not only true teas, but there are many herbal infusions that are commonly referred to as “tea” in everyday language.

Here are 21 major tea types and categories of teas found in Japan—not a complete list, but a good place to start.

Major Types of Japanese Green Tea

Sencha 煎茶

Japan’s most common green tea, lightly steamed for a bright, refreshing, grassy flavor.

Fukamushicha 深蒸し茶

Deep-steamed sencha with a rounder, mellower flavor and a deeper green color.

Kabusecha かぶせ茶

A shade-grown tea that sits between standard sencha and gyokuro in flavor and aroma.

Gyokuro 玉露

A shade-grown tea that is naturally sweet and extremely delicate. It is widely regarded as the most premium tea in Japan.

Matcha 抹茶

A shade-grown green tea that is stone-milled into a fine powder and whisked into a frothy drink

Kukicha 茎茶

A tea made from twigs and stems, offering a nutty, earthy character and subtle natural sweetness.

Mecha 芽茶

A tea made from young buds and tips, aromatic with a pleasantly sharp, astringent bite.

Genmaicha 玄米茶

Green tea blended with toasted brown rice for a nutty, warm, cereal-like depth.

Hojicha ほうじ茶

Roasted green tea with a toasty, caramel-like aroma and low caffeine.

Other Traditional Japanese Teas

Sanpincha さんぴん茶

A jasmine tea popular in the Ryukyu Islands, made with Chinese-style green tea as the base.

Kohakkocha 後発酵茶

An umbrella term for post-fermented teas, dark and tart, made in parts of Shikoku Island and Toyama.

Wakocha 和紅茶

An umbrella term for black tea made from Japanese tea leaves, generally lighter and more floral than other black teas.

Traditional Japanese Infusions (Tisanes)

Kombucha 昆布茶

A salty kelp infusion with strong umami (yes, this is the real kombucha)

Umekobucha 梅こぶ茶

A kelp infusion specifically flavored with ume.

Mugicha 麦茶

A caffeine-free roasted barley infusion drunk daily in many Japanese households.

(Ask for “water” at a Japanese dinner table and you might be handed mugicha instead.)

Kuromamecha 黒豆茶

A roasted black soybean infusion with a nutty aroma.

Gobocha ごぼう茶

A burdock-root infusion with earthy, mushroom-like notes and a reputation for digestive benefits.

Sobacha そば茶

Roasted buckwheat kernels brewed into toasted-grain tea.

Kuromojicha クロモジ茶

An infusion made from the Japanese endemic Lindera tree, known for its clean, herbal fragrance.

Dokudamicha どくだみ茶

A fish-mint infusion with a divisive scent, valued for traditional health benefits.

Ucchincha うっちん茶

A turmeric infusion commonly drunk in the Ryukyu Islands.

(Supervised by Takeshi Dylan Sadachi)

History of Japanese Tea

All teas—including green tea, black tea, oolong tea and so on—come from the Camellia sinensis plant. What differentiates them is how the leaves are processed, through varying degrees of oxidation, fermentation, roasting, or added flavors/scents.

Some people, after glancing at Wikipedia, whitesplain Japanese people that “green tea comes from China, so it isn’t a Japanese tradition.” which is true, but so does every other form of tea. China is the birthplace of the actual tea plant, tea cultivation and processing; Japan later adapted these techniques to suit its own tastes and rituals. In that sense, Japanese green tea is no more “Chinese” than English Breakfast or Earl Grey are “Chinese” (though importantly, Japan can cultivate tea and has been for over 1000 years.)

Tea was first introduced to Japan by Zen Buddhist monks in the 8th century, who brought it back from their studies in Tang-era China. According to Chinese legend, tea itself was discovered thousands of years earlier when a breeze carried stray leaves into Emperor Shen Nong’s cup of hot water—a lucky accident that sparked an entire civilization of tea drinking.

Even the word tea itself has Chinese origins. It derives from “茶”—pronounced te in Southern Min dialects and cha in Cantonese—evolving into tea, cha, and chai across the globe. Today, the word is loosely used to describe any hot infusion, from mint tea to rooibos. Technically, however, drinks like these aren’t tea at all since they don’t come from Camellia sinensis—just as “cauliflower rice” isn’t really rice and “plum wine” isn’t wine in the vineyard sense (its process resembles limoncello more than Chardonnay).

In Japan, tea evolved in a distinct direction. The country focused almost exclusively on green tea, developing its own varieties—sencha, gyokuro, hojicha, and matcha—each tied to local terroir and ritual. By the 1600s, Dutch traders in Nagasaki were already exporting Japanese green tea to Europe, making it one of the first Asian teas to reach Western markets.

(Originally published by Jessica Thompson as Beyond Matcha )