October 9, 2025

Lafcadio Hearn (Yakumo Koizumi) and His Many Lives

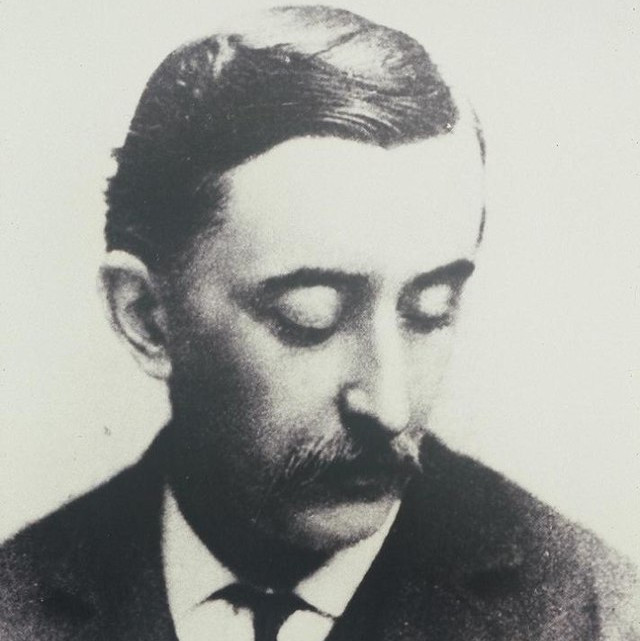

The Irish-Greek wanderer who became Japan’s foremost folklore chronicler

From late September 2025, NHK’s Asadora,Japan’s most-watched morning drama series and a national cultural staple, debuted “The Ghost Writer’s Wife”, telling the story of Setsu Koizumi, the wife of Greek-Irish-Japanese writer Lafcadio Hearn.

In Japan, “Koizumi Yakumo” is already a household name, but by turning the spotlight on his wife, the drama offers a fresh perspective. Outside Japan, however, Hearn himself remains less familiar, so let’s start with a quick recap of who he was.

Based in Japan: Yakumo Koizumi (Lafcadio Hearn)

If Metropolis had existed in 1890, Lafcadio Hearn would surely have been an interviewed feature in our “Based in Japan” series.

But perhaps it’s not too late to spotlight this extraordinary man who lived a truly unique life: a British citizen of Irish-Greek descent who found success as a writer in the United States before possibly becoming the first Westerner naturalized in Japan and the nation’s most celebrated specialist on Japanese ghosts. Yes, it’s a mouthful, isn’t it?

He is a significant figure in Japanese literature, known to almost all Japanese people solely by his Japanese name, Koizumi Yakumo. Growing up in Japan as a child, I assumed he was simply a Japanese man, which, in many ways, he truly became. Shogun has its own fascinating story with the first “white samurai,” but Lafcadio Hearn definitely deserves the spotlight, too.

At the age of 40, Lafcadio Hearn arrived in Japan just 22 years after the end of the Shogun-ruled Edo Period and the opening of its ports to the world. In this era of Japan, in the early phases of undergoing dynamic transformation, he was able to collect and archive traditional folklore—often specific to certain regions and not part of a centralized body of knowledge—before they could be forgotten and lost.

(An Attempt to) Summarize Hearn’s Many Lives

[Early Life]

Lafcadio Hearn was born in 1850 on the British-occupied island of Lefkada (which he is named after) between an Anglo-Irish father who was a British Navy surgeon and a local Greek mother from Kythira who was said to be of Arab descent.

Shortly after his birth, his father was reassigned to the British West Indies but did not inform the military about his marriage to a local woman for career advancement. Instead, he arranged for his wife and son to move into his family home in Dublin, then under British control. The Greek mother spoke no English and faced discrimination from her husband’s Protestant family because of her Orthodox faith, which ultimately led her to return to Greece and divorce. Lafcadio was then placed in the custody of his Catholic grandaunt. A relative of her late husband and Hearn’s distant cousin, Henry Molyneux, also supported Hearn financially. The two enrolled him in a Catholic church school in France and a Catholic seminary in Durham, England. During this time, he suffered an injury to his left eye, resulting in permanent blindness.

His birth and early life were shaped by the subject of British imperialism, which is reflected in his anti-colonialist views and his interest in cultural preservation. Additionally, his complicated experiences with Christianity made him critical of organized religion—enough for him to abandon his biblical first name, “Patrick,” in favor of his middle name, “Lafcadio.” His skepticism ultimately fueled his fascination with the supernatural and paganism, particularly Greek mythology and folklore.

[Young Adult]

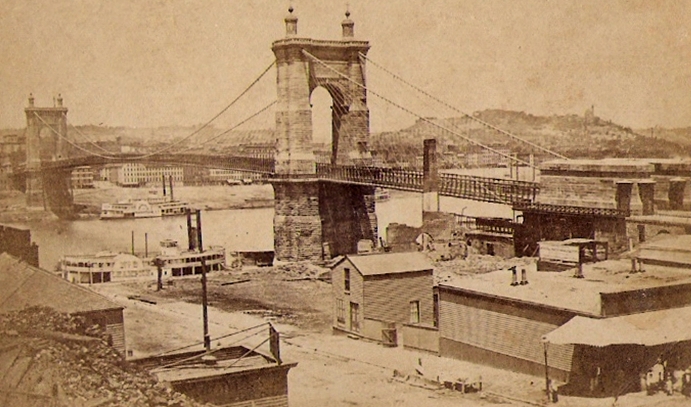

When his grandaunt and now her financial advisor, Molyneux’s business failed, 17-year-old Hearn ended up in London’s East End, where he worked in various workhouses to make ends meet. At 19, Hearn received a one-way ticket to New York from Molyneux, who suggested he seek out his brother in Cincinnati, Ohio, to help establish a better life in the U.S. However, upon arrival, Hearn was thrown out to the street and made a living doing odd jobs. Eventually, he managed to secure a job as a reporter at The Cincinnati Enquirer, marking the start of his successful writing career in the U.S.

During this time, he fell in love and married a woman named Alethea. Just as he felt everything was finally going well—the American Dream—he was suddenly fired from the newspaper. The reason: Alethea was Black. Interracial marriage was illegal in many states (and these laws were not fully repealed in all states until as recently as 2000).

Eventually, he moved to multicultural New Orleans, where he spent over a decade working as a writer and editor, mainly focusing on topics like Voodoo and Creole culture, utilizing his French proficiency. During the 1884 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans, he visited the Japanese pavilion, which sparked his interest in Japanese culture. After spending two years in French Martinique as a correspondent for Harper’s, he relocated to Japan as a newspaper correspondent but terminated his contract immediately upon arrival.

A Journey into Japanese Folklore: Setsu and the San’in Region

With assistance from Japan-based British academic Basil Hall Chamberlain, he began his career as an English teacher (some things never change). He first arrived in Matsue, now part of Shimane Prefecture in the San’in region, where he met Setsu Koizumi. Their encounter became a turning point in his life.

It was Setsu who first shared the region’s ghost stories and folktales with him. It was Setsu who first shared the region’s ghost stories and folktales with him. The San’in region, with its deep Shinto roots, carries a mysterious “pagan” quality, especially from a Western point of view. Through Setsu’s stories and his life in Shimane, Hearn also came to realize how these stories existed across Japan, often unique to its region.

Given his interests in anything “pagan”, including Celtic myths, Greek legends, and Voodoo, it was only natural for him to become fascinated with Japanese folklore. His most famous work, Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, was published shortly before his death in 1904. In the introduction, he notes that stories were gathered either from old Japanese texts or were collected by asking around as they were orally passed down. Many were obscure regional tales, like Hoichi the Earless and Yuki Onna, now widely known as Japanese folklore nationwide largely due to Hearn’s efforts.

Hearn’s Japan

These folktales began to emerge or gain popularity during the preceding Edo Period. Now, Japan was all about industrialization and Western science; intellectuals often focused on translating and emulating Western literature. In this climate, Hearn and Setsuko were instrumental in preserving the stories that might have otherwise faded into obscurity.

Hearn was remarkably appreciative and adaptable to other cultures for his time. He eventually fell out with Chamberlain, who had helped him find work in Japan. Chamberlain was notoriously dismissive of Japanese literature, calling it “intolerably flat and insipid,” and believed in the superiority of Europe. This echoed the views of his brother, a prominent academic in the emerging field of “racism” (yes, it started as a scientific philosophy like other “-ism”s).

Unlike many foreigners of his time, who stayed within the bubble of Foreign Settlements, Hearn’s frequent moves around Japan, often as an English teacher, led to more genuine interactions with locals. He was even offered a position at Yokohama’s Victoria Public School for British students but quit immediately when the principal’s wife barred him from their home due to his blind left eye. Perhaps from this experience or his own inclinations, he did not interact with international residents often. Visiting a temple, he even expressed irritation at “signs in English forbidding injury of the trees, necessitated by the activities of foreign tourists”.

Hearn’s view of Japan was, perhaps, through rose-tinted glasses. After a tumultuous life in Europe and the U.S., he longed for a peaceful life in what he saw as a traditional society. He disliked the Western-style buildings quickly springing up in Japan, having arrived during the most transformative time in Japanese history. Lafcadio Hearn glimpsed remnants of Edo-period Japan, but the Japan he cherished was already beginning to disappear. Some scholars criticize Hearn for projecting an exoticized, often inaccurate, image of Japan. Yet, as a man who endlessly searched for a sense of belonging and spent the rest of his life here, I can only hope he found peace in Japan.

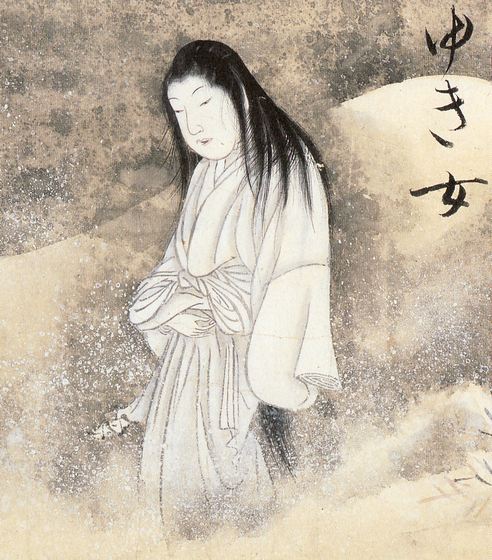

Yuki Onna

A woodcutter, stranded in a snowstorm, encounters a ghostly woman who spares his life on the condition that he never speaks of her. Years later, he marries a beautiful woman and enjoys a happy life with their 10 children. One day, he wistfully mentions her agelessness and how it is mysterious, like the “snow lady.” She then reveals her true identity as the “snow lady” he met years ago and, betrayed by his broken promise, vanishes, leaving him only with their children and the haunting memory of her

(Illustration by Suushi Sawaki, from the Hyakkai-Zukan, circa 1737)

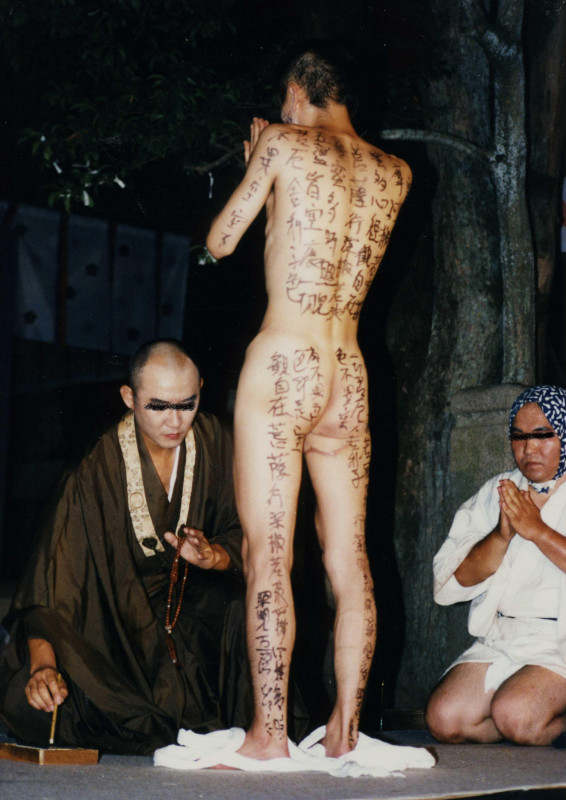

Hoichi the Earless

Hoichi, a blind musician, lives under the care of a Buddhist priest. One day, the priest notices Hoichi’s absence and discovers he has been performing for fallen samurai spirits. To protect him, the priest paints sutras on Hoichi’s body. When the samurai returns, he finds Hoichi invisible and rips off his ears, the only part the priest forgot to paint. Though injured, Hoichi survives, gaining fame as a musician

(Photo by Akiyoshi Matsuoka, an open air play at Suma Temple in Kobe, circa 1984)

Read about the San’in region’s spiritual culture—where Hearn lived, met Setsu and found inspiration for his ghostly tales:

Visiting San’in: Japan’s Sacred and Slightly “Pagan” Region