August 1, 2017

The Melancholy Of Summer

The art of Kiyokata Kaburagi, a ukiyo-e master

Most people might associate summer with the beach, cold drinks and fun in the sun, but the season isn’t nearly as cheerful in Japanese art. Starting all the way back with the Kokin Wakashu, an anthology of poems from over a thousand years ago, Japanese summers were always synonymous with one thing: rain, from the early May rains known as samidare to the rainy season in June and July known as tsuyu. Then there are the Japanese cicadas that can live up to 17 years but only spend about four weeks above ground as adults before dying off in the summer, which, over time, has made them the symbols of impermanence and the fleeting nature of life.

Between that and the overcast, rainy skies of tsuyu and samidare, summer has long been a very melancholic theme in Japan. But what makes the Natsu no Keshiki (Summer View) exhibition at the Kaburagi Kiyokata Memorial Art Museum in Kamakura so interesting is that it manages to seamlessly mix summer melancholy with a celebration of feminine beauty.

First, a little background. Kaburagi Kiyokata (1878–1972), was a Japanese artist specializing in “bijin-ga” (portraits of beautiful women), which is both the genre’s literal translation and its succinct summary. The art is usually considered a subgenre of “ukiyo-e” (portraits of the floating world), an art movement that emerged in 17th century Japan and focused on city dwellers engaging in everyday activities. As such, the subjects of bijin-ga were most often women from the less affluent parts of big cities, and because Kaburagi had an affinity for those kinds of people, it was no surprise that he became a bijin-ga artist himself. But there was something that separated him from all the painters of beautiful women that came before him.

Traditional bijin-ga art, as seen, for example, in the works of Utamaro Kitagawa, an ukiyo-e artist popular during the late 18th century, has always been very impressionistic in its approach to beauty. It didn’t really strive for realism but rather for an idealization of beauty somewhat inspired by traditional Chinese art of the Tang Dynasty. This usually resulted in early bijin-ga women being depicted with snow-white skin, beautiful kimonos, intricate, rigid hairstyles, and very little detail given to their eyes, mouths or noses.

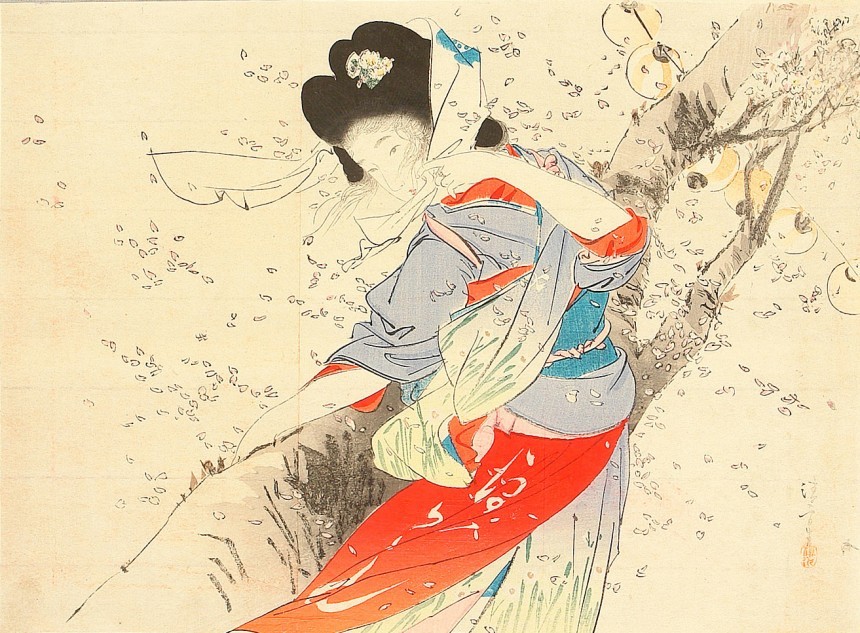

Kaburagi Kiyokata took a different approach. As seen not only in Natsu no Keshiki but really most of his work, Kaburagi’s beautiful women have distinct red lips, eyes that are more than two tiny slits and flowing hair that looks like ink dissolving in water. Their skin is also more flesh-colored than the majority of bijin-ga, making them look much more real and alive as a result. But Kaburagi’s bijin-ga portraits set in the summertime are of particular interest because of how they combine Kaburagi’s depiction of beauty with the inherent melancholy of Japanese summer, especially in his use of color. While you’d expect an exhibition titled “Summer View” to be very light, vibrant and bright, Kaburagi’s portraits and sketches actually use a lot of blacks and grays, while all the other colors are kept soft and dull.

Scene wise, his calmest art pieces are set inside homes and depict, among other things, young women clad in yukata (summer kimono) doing their makeup, relaxing by the window, or enjoying a firework show. Those set outside, however, are significantly gloomier and may show women fighting against a strong wind, or a young couple in a world somewhere between reality and the realm of spirits. In all of those portraits, humans are usually depicted with distinct lines, while trees, flowers and other scenery are mostly seen as if from behind a haze or a fog, most likely inspired by the humid heat of Japanese summer. But it could very well be that Kaburagi was drawing a line between the world of humans and nature while making it abundantly clear that summer belongs to the latter. It’s a time when beauty primarily thrives indoors, in contrast to the turbulent outdoors with its tsuyu and samidare which, incidentally, just happens to be phonetically similar to midare, meaning “confusion.” That, in a nutshell, is the essence of Kiyokata Kaburagi’s melancholic, summertime bijin-ga.

The exhibit ends on August 27th.