Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on September 2010

Unless you’re a suit-wearing mutant with a handycam for a head and an uncontrollable desire to breakdance in cinemas, the anti-piracy advert that plays before films in Japanese movie theaters probably doesn’t strike a chord. Presumably, there are still a few stubbornly traditionalist bootleggers out there who would attempt to sell you a blurry spasm-cam mpeg of Avatar shot on their PHS. But in an age where it’s possible to download high-definition rips of Adam Sandler’s entire oeuvre in a few minutes, and prominent DVD rental chains sell stacks of blank discs next to the counter with a figurative nudge and a wink, it feels a bit redundant to say “No More Eiga Dorobo” to a captive audience who’ve just taken an ¥1,800 gamble on your latest celluloid conglomeration.

Forcing all filmgoers to sit through warnings about illegal activity in which only a sub-atomic portion of the population indulges has far more to do with satisfying the Japan and International Motion Picture Copyright Association than the public. And in much the same way, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised when domestic producers of multiplex fodder continue to push high-concept star vehicles designed first and foremost to fulfill the needs of the business interests involved—while seeming to ignore audience demand.

One recent example is last year’s Kochikame, a TV series starring the gratingly cartoonish Smap pitchman Katori Shingo, of the powerful Johnny’s Jimusho pretty-boy factory. TBS had intended to establish the show, which is based on a popular kids’ manga, as an ongoing fixture. But despite incessant promotion and a prime family-friendly slot at 8pm on Saturdays, viewers were quick to sniff out the desperation. The show’s flimsy conception and over-reliance on celebrity cameos saw it end its uncelebrated run with a dismal average viewership rating of 9.3 percent.

So the recent announcement that this notorious failure would be receiving the big-screen treatment was greeted with a resounding “Heee?!” by entertainment insiders. One headline in entertainment tabloid Cyzo summed it up nicely: “Does TBS intend to take a lover’s leap with Johnny’s?”

The same thing happened back in 2007 with another Johnny’s idol, Koichi Domoto, and a Friday night series called Sushi Ouji. In this case, a theatrical sequel was actually shot before the TV show that was to precede it, so when the drama suffered from poor ratings, the parties involved had little choice but to shunt the film into cinemas, where it opened in 6th place and slipped shamefacedly out of the top ten the following week. It’s also possible that the film’s sponsors pushed advance tickets on to as many of their staff as possible to drive up the opening weekend total—a practice which is apparently not uncommon.

One might wonder why any business would persevere with such a loss-making proposition, let alone be reckless enough to repeat it. But the truth is that control-freak talent agencies reign supreme in the name-recognition-driven world of TV programming. They aren’t shy about throwing their weight around to protect their money earners’ delicate showbiz careers. If by chance one station decides to make a stand, the agency can always take its little pride and joy off to a competitor. The same applies for the entertainers themselves: for all but a few of the most famous names, disagreeing with an agency’s directives is usually a one-way ticket to obscurity.

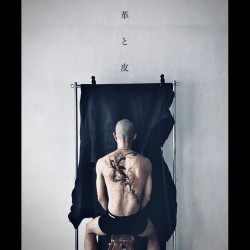

Illustration by Shane Busato

With the decline of Japan’s major studios, television companies have stepped in to fill the vacuum. The result is the introduction not only of the low production values, pedestrian direction and tonal inconsistency characteristic of homegrown television dramas, but also the obsequious deference to talent agencies. How else can you explain the casting of Katori as Zatoichi? Or Eiji Wentz as Gegege no Kitaro? Or Koike Teppei as a homeless junior high student? You could argue that each actor brought certain qualities to his role and delivered certain audiences to the films, but you’d be going out on a limb if you said that they were logical choices.

Showbiz politics should be treated the same way as special effects: if they’re too blatant, it becomes hard for audiences to take a film seriously. Take the TBS production, Rookies: Sotsugyo. True, it was an utterly worthless TV adaptation that epitomized the worst aspects of mainstream Japanese cinema. But its monomaniacal dedication to delivering exactly what the fan base wanted made it the top grossing film of 2009, and even propped up the network’s ailing finances. Sucking up to talent agencies might be a necessary evil for commercial filmmakers, but pandering to audiences is far more lucrative.