May 11, 2021

The Bridge at the Center of the City

Watching the flow of time from Nihonbashi

By Metropolis

The center of Tokyo is not a square or a tower or a statue, but a bridge. All distances from Tokyo are measured from this bridge, which is made of stone and bronze and called Nihonbashi, meaning “Japan Bridge.” A highway was built in haste in the 1960s, just before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and bathes the bridge’s old stone and road in shadow and darkness. Now, the space where the bridge straddles the river is ugly, and a professor, in 2006, put the bridge on an “Ugly Japan” list. But before there was the highway and ugliness and a Starbucks on the corner, Nihonbashi was made of wood, and Tokyo was called Edo.

In “Tokyo Before Tokyo: Power and Magic in the Shogun’s City of Edo,” Timon Screech recounts Edo’s urban topography, pleasure districts and bridges. A reviewer mused, “the book resembles, at the most superficial level, a particularly beautiful Fodor’s Guide to a vanished city.” This Edo city was the Shogun’s city, a space of power that was militarized and grand. To stand on Nihonbashi then was to see vistas: of the city, of power, of scale.

The bridge, writes Screech, was “the node that bound Edo together and render it internally whole.” It was the first stop on the Tokaido, the road that connected Edo to Kyoto. Now, the vistas have been lost and many of the canals blanketed in darkness.

The bridge is a harbinger of change, a topographical feature upon which the story of the capital is inscribed and written. And so, the story of Nihonbashi, also the name of the surrounding area, is the story of the eastern capital and a flux and creeping urbanism. It is also a story of Edo’s continued hold—hidden but tenacious—on contemporary Tokyo. As Nagai Kafu, a child of Bunkyo, penned in his diary at the dawn of the 20th century: “Every last building, from the Imperial Palace on down, was erected by people of Edo.”

When Edo became Tokyo in 1868, and the city soon became one of stone and railways, the bridge held a perennial fascination for artists and writers, and soon photographers. In 1881, Kobayashi Kiyochika captured the new capital in flux with the series of woodcuts “Famous Places of Tokyo,” which included a rendering of the bridge. “Night at Nihonbashi” gazes upon the bridge from the land and strips the scene of colors. Street lamps — symbols of modernity — line the bridge, and carriages fill the road. The pedestrians and buildings are rendered as anonymous black silhouettes—faceless but clad in Western dress.

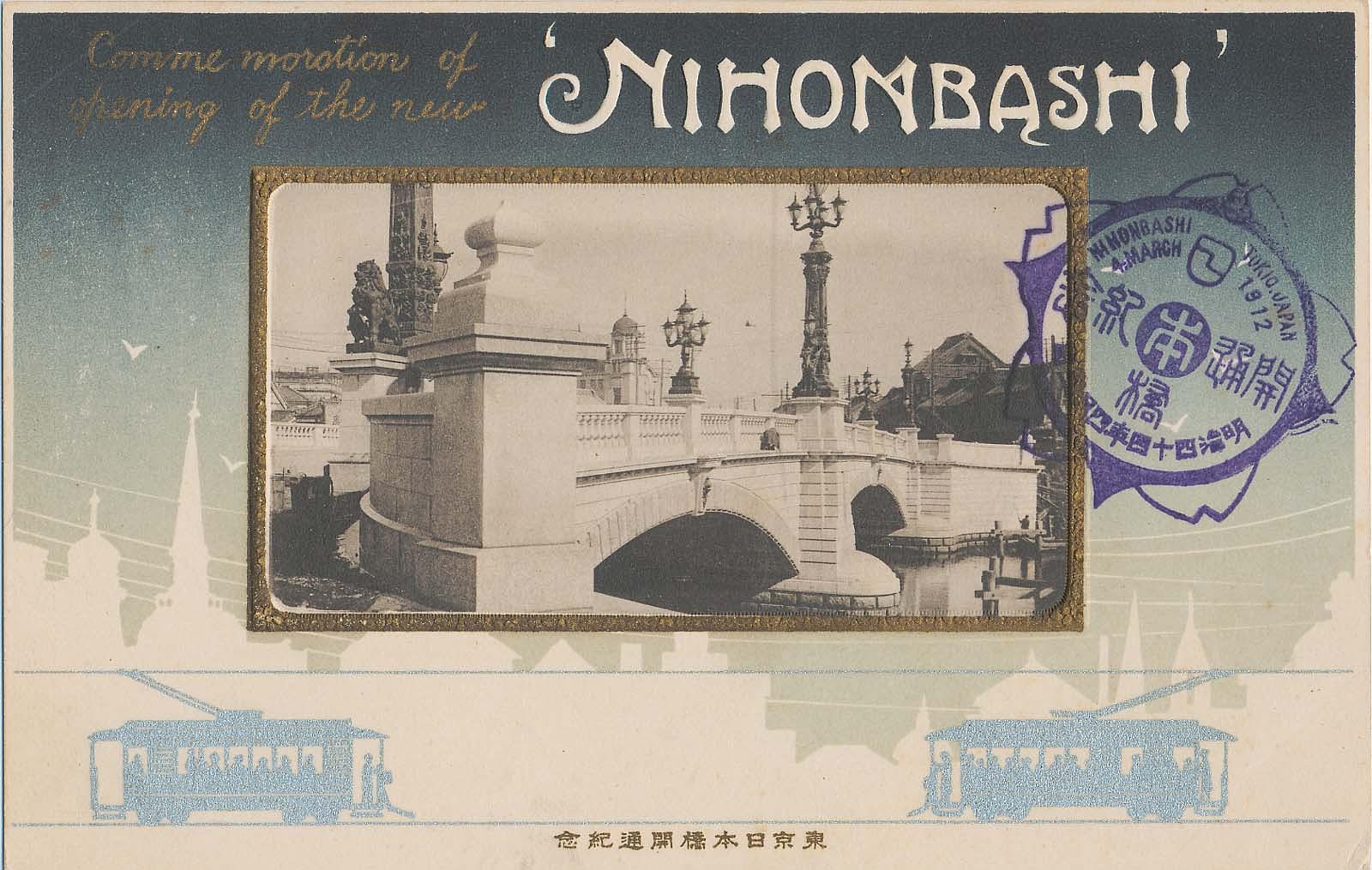

In 1911, stone replaced the wood of the bridge at the center of the city. To mark the opening of the new Nihonbashi, the publisher Naniwaya released commemorative postcards, which included a photograph of the bridge: imposing and grand. The bridge survived the 1923 earthquake and fire, which destroyed much of the city’s eastern half, and a postcard from that year shows bodies and debris strewn beneath the bridge.

The scene is gruesome and grotesque, and though the bridge is unseen, the photo was taken from its vantage point, and so the bridge stood: firm and unwavering. The city government pronounced that, despite the damage, Tokyo would remain the capital. This meant that so, too, would the bridge remain the heart of the city.

In the 1930s, as Japan began its war in China, Tokyo became a wartime capital. Photographers and artists searched for the banal and apolitical: this was found in the bridge’s details. In 1937, Hiroshi Hamaya, a photographer, then at the dawn of his career, captured a statue of a kirin (mythical creature) set upon the bridge. The kirin is winged and forged in bronze. The beast is set on the side of an ornate bronze column, from which lamps protrude. In 1946, the year after the war ended and the occupation began, Hiratsuka Un’ichi, who would go onto fame in America, again rendered the column and kirin; it was monochrome and like Kiyochika decades earlier, wrought at night.

Tokyo thrived and swelled, and, in 1964, it was set to become an Olympic city (after the 1940 games were canceled). The Metropolitan Expressway was built over the Nihonbashi River and so over the Nihonbashi: a canopy of the new that enveloped the old. Robert Whiting wrote, in a walk in the moments before the game, “I was dismayed to see its once-charming appearance completely ruined by the massive highway just a few feet overhead, like a giant concrete lid, obliterating the sky.” The views were lost to an endless sprawl of highway, a space as unremarkable as it was ugly.

In the 2000s, photographer Tetsugo Hyakutake captured the bridge set beneath the highway in two frames–one during the day, the other at night. He looks across the water, from west to east, and captures the bridge as cocooned in urbanism and crowding. Everything of the bridge’s grandeur—the vistas, the scale, the details—have been lost, swallowed by the highway and buildings and cars.

If you walk to the bridge today, the stone is still white, and the bronze lamps still stand. The road is congested, and the sidewalks are crowded. The highway towers above and the vistas are gone. In the spring, cherry blossoms bloom where the bridge meets the land. The bridge is stained with scorch marks from American bombs during the Second World War.

For the 2020 Olympics and Paralympics, Nihonbashi, the district, was set to become the “Olympic Agora,” a center of festivities, a space for food and drink. It was modeled on the Agora in ancient Greece, which, according to the IOC, was “where the people gathered to eat, drink, sing, buy, sell, discuss politics and revel in urban life.” Since COVID has spread and the games have been postponed, Tokyo’s Agora seems unlikely. But other changes are afoot, ones which offer a promise of revival: the highway is to be removed and set underground, as the waterfront is to be revitalized. The lost vistas will return, now hampered by smog and urban sprawl. The days of Edo are gone. But the bridge remains.

Want to know more about the history and development of Tokyo?

America’s Tokyo

Revisiting the capital 75 years after the American Occupation began

The Diversity of Tokyo’s Architecture

Photography highlights from Metropolis readers