September 13, 2018

Pure Pleasure by Kate Groobey

Interview with the prize-winning artist

“Give me what I want” — the words are uncompromising, and could even be threatening, but there is nothing remotely violent about the playful figure dancing joyfully in front of me. Depicting subjects is not enough for Kate Groobey – she has physically inserted herself into her art, donning her own nude paintings as a costume and creating videos of the female form, moving with vivacity to music of the artist’s creation.

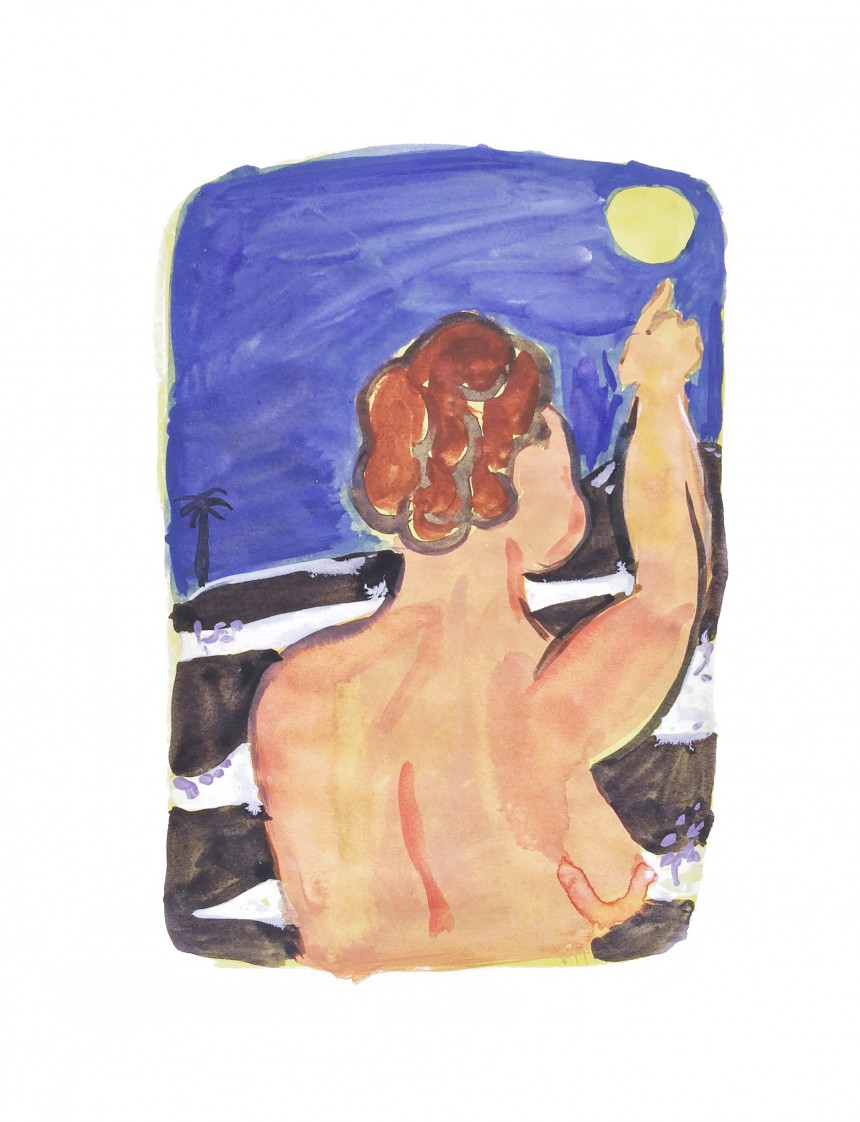

“Pure Pleasure” problematizes roles from the outset: who is the artist and who is the subject? Who gets to look and who is looked at? Who has the right to pleasure? The exhibition explores an underrepresented perspective in the history of art — that of a woman painting her female lover with a desiring female gaze. “Pure Pleasure” consists of a series of watercolor nudes, stills and videos; of Groobey’s partner sleeping, sunbathing, eating watermelons, dancing and generally exemplifying the myriad ways one can practice joie de vivre.

Groobey is the fourth winner of the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation’s Art Prize, which offers a British artist a solo exhibition in Japan. The artist hails from the rainy north of England but divides her time between Yorkshire and the South of France. Mediterranean sunshine, a sea-breeze, good food and wholesome outdoor activities are palpable in the works of “Pure Pleasure,” which all display a dynamic physicality. It’s significant that for many of the nudes, Groobey’s partner is placed a little bit in front of the background, evoking the sense of one of Picasso’s subjects stepping out from the frame and reclaiming her agency after a lifetime of objectification.

Groobey’s palette may be light, but “Pure Pleasure” is not shallow. There is something poignant and courageous about the exhibition; pleasure claimed with a life-affirming fierceness, only possible to those who have known despair. It’s masterful that Groobey keeps the ostensibly ‘subversive’ perspective of a queer female gaze easy-going in the face of an artistic canon which denies her existence. That being said, “Pure Pleasure” has a message that transcends gender or sexual orientation. Pleasure is allowed, it is necessary and good. This idea itself is revolutionary in a built-up, crowded city like Tokyo, notorious for glorifying overwork and self-punishment.

“Pure Pleasure” runs at Mizuma Art Gallery until October 13 2018. Entry is free.

Go. Chances are, there’s not enough pleasure in your life.

Interview with Kate Groobey

Julia Mascetti: Congratulations on winning the 2018 Daiwa Foundation Art Prize. How does it feel to be exhibiting your first solo show in Japan?

Kate Groobey: Thank you. This will be not just my first solo show but my first visit to Japan. My desire to come to Japan is rooted in its influence on western Modernist painting, stemming from the formal impact on painters like Cezanne and Manet when industrialisation made cheap reproductions of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints available in Europe, and also from its zen philosophy, which I discovered over a decade ago when I practiced a Japanese martial art, jiu jitsu.

Two years ago my partner and I started an experiment to live and work on the road, seeing how that might change us and change our work. We have bartered things and taken up residencies (and entered prizes) to open up travel opportunities. The road trip is evident in my latest work in the contrasts between my own upbringing and the places we have traveled. The “Pure Pleasure” series showing in Tokyo is based in L.A, a place so sexy, superficial, sunny and cheerful and absolutely at odds with my native Yorkshire roots which are rainy, real, down-to-earth and grumpy. I will make my next series of work based on my trip to Japan.

JM: For “Pure Pleasure,” you worked from an underrepresented perspective in the history of visual art: that of a woman on woman, with a desiring female gaze. Much of Japanese popular culture is dominated by the heterosexual male gaze, even more so than the UK where we both are from, I think. Female bodies are used to advertise everything and pornography is available in convenience stores. Given this background, how do you think “Pure Pleasure” will resonate with Japanese audiences?

KG: My partner, in one of the “Pure Pleasure” films, Give Me What I Want, challenges us, telling us she’ll give us what we want, but only if we give her what she wants. She’s making sure that we know that her pleasure is as important as ours. The male gaze, on the other hand, is strictly a one-way-street.

She holds authority again in the moon pieces of my “Pure Pleasure” series. She is pointing to the moon, directing our gaze so that we understand her desires. She loves the moon, she loves to look at the moon, to moon-bathe, and in one of the films tells us that she wants the moon, and indeed she takes it from the sky to dance with it. I believe that moon-gazing, insofar as it connects with the idea of transient beauty, is something that will resonate with Japanese audiences.

Many of the works in “Pure Pleasure” focus on her pleasure, not ours. In “Bird dance” her arms grow longer with desire, in Altered State her eyes close in hedonistic trance and in Give Me What I Want her hands drum out the beats of her demands, not ours. The male gaze, on the other hand, requires a passive nude.

If looking at the still paintings you feel that she is vulnerable to the male gaze, or that you are lured in by a male gaze, it’s a trap, you will find it blocked by the performances, where she jumps out at you from the painting, confronting you with the full force of all her agonies and ecstasies, far from passive.

JM: The selection board of the Daiwa Art Prize described your work as, “dynamic, refreshing, life enhancing.” When I saw “Pure Pleasure” for the first time, I too was struck by a sense of joy and playfulness. ‘Pleasure’ can connote many concepts, such as joy, doing something ‘for pleasure’ as opposed to ‘for business,’ or sexual pleasure. What did you have in mind when titling the exhibition?

KG: When we were in Los Angeles something my partner said inspired the title: she flippantly said, ‘I am pure pleasure’. That phrase seemed to me to sum up my feelings about the city, about paint, about her and about the time of year; it was the start of summer.

It was also the end of a grief cycle. My father had recently died after three years with cancer. Seeing him lose the ability to step outside to tidy his garden or drink his cup of tea brought to me a different appreciation of the importance and joy in simple pleasures.

JM: I’ve often thought that, as a woman, the male gaze dominates art and society to such an extent that it is very difficult to subvert it or escape from it when creating. Sometimes when I see a female self-portrait, I do feel that the artist has ended up catering to the male gaze to some extent, even if she did not intend to. When creating the artworks, did you consider how to differentiate your work so that a female gaze is communicated instead of a male one? Or are intentions and the identity of the artist more important?

KG: I asked myself the same question. At LACMA, I stood looking at a Picasso painting called “Man and Woman” where the male figure is pointing a knife at the woman’s vagina, when a male security guard (laughing) said, “Picasso was a pig!” That encounter really stuck with me. I wanted to understand myself, would I become a pig like Picasso if I painted my lover? There are strategies of resistance in my Pure Pleasure series, I like to think it’s subtly subversive. You have to see the show to decide for yourself if I’m as big a pig as Picasso.

Intentions and identity are important. We aren’t familiar with as many female artistic worlds as we are male ones. We should be.