November 12, 2024

“They Ripped Up My Resignation Letter”: 1 in 5 Japanese Workers in Their 20s Turn to Resignation Agencies

Young workers turn to resignation agencies for their mental health

A new survey from Mynavi Corp. shows a significant rise in resignation agencies across Japan that help people quit their jobs. But why?

With deep remorse, Mr. Iida sank to the floor. His knees touched the cold concrete, and he bowed so profoundly that his head almost met the ground. “Dogeza,” the most sincere way to apologize for a serious offense, performed by a salaryman in his boss’s office. The reason? Mr. Iida submitted his resignation. But, after a brief silence, there was a tearing sound, and he realized his boss had ripped his resignation letter to shreds. The message was clear: you are not allowed to quit.

Advertisement

In Japan, leaving a job can be challenging. Traditionally, employment is considered a lifelong commitment. Though Japan is moving away from this outdated mentality, many traditional companies still expect employees to work until retirement without changing jobs.

For some older generations, there is still a deep sense of shame in switching jobs, as work ethic in Japan is closely tied to loyalty and respect. Japanese law technically guarantees the right to quit, but doing so is often seen as disrespectful, as companies invest time and money in training employees. It is a mutual investment — the company invests in you, and you, in turn, commit to advancing within the organization over time.

“I Can’t Take This Anymore”

Mr. Iida performed the dogeza three times before his boss, apologizing for “letting him down,” yet his resignation still wasn’t accepted. He had to find another way out.

He contacted the resignation agency Momuri, whose name translates to “I Can’t Take This Anymore.” For around ¥22,000, they handle the entire resignation process, contacting the boss on behalf of the client, negotiating with the company, and even recommending lawyers if legal disputes arise.

According to Yujin Watanabe, a spokesperson from Albatross Corp., which manages Momuri’s services, their typical client profile is young people in their 20s who work for small to medium-sized companies, often in corporate or welfare industries.

Mr. Iida is far from alone in seeking outside help to resign. Since 2022, Momuri, just one independent resignation agency, has received 35,000 requests from people needing assistance quitting their jobs.

1 in 5 in Their 20s Use Resignation Agencies

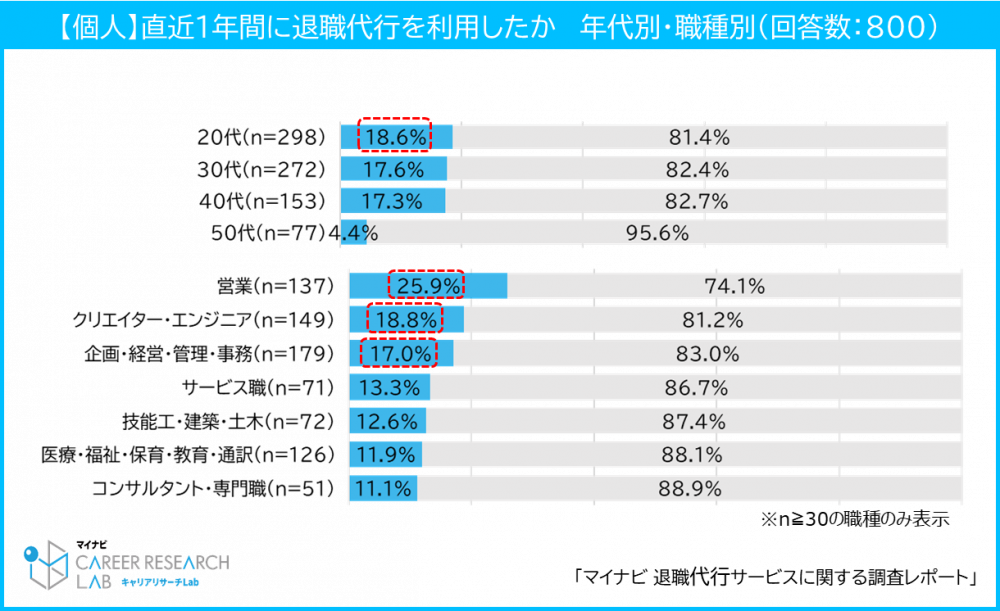

A new survey by the employment information provider Mynavi Corp. found that nearly 1 in 5 people in their 20s who quit their jobs in Japan last year used agencies like Momuri to help them.

The survey, which included employees ages 20-50 who quit jobs between June 2023 and June 2024, shows that 18.6% of those in their 20s used these services, 17.6% were in their 30s and 17.3% were in their 40s. Only 4.4% were in their 50s, indicating that older employees tend to stay in jobs longer—even if conditions are poor—as the younger generation is more likely to adjust to their needs and wishes.

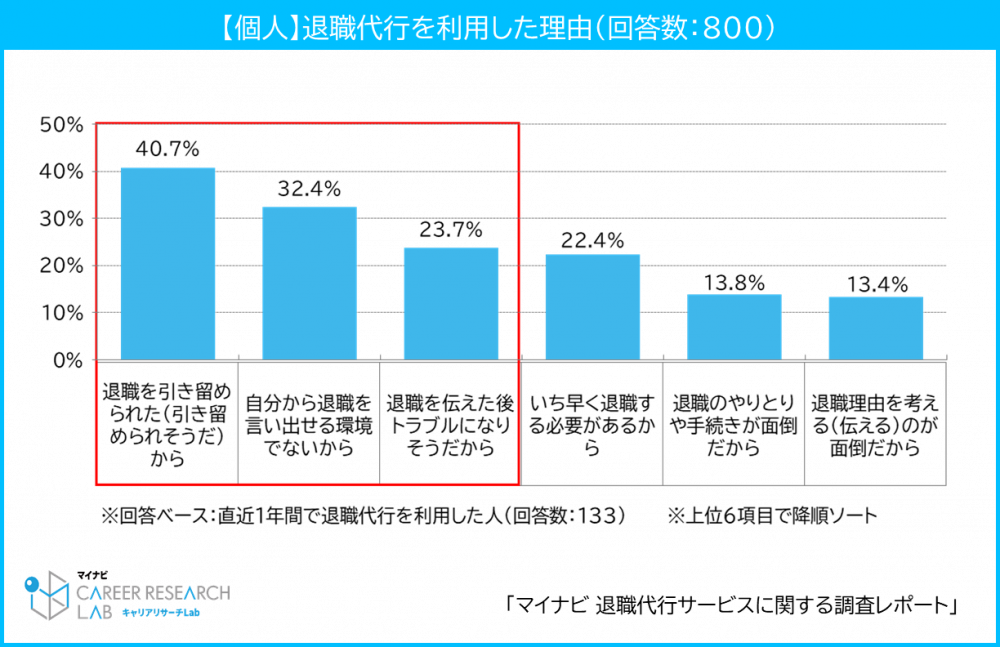

The top-cited reason for using resignation agencies, at 40.7%, was that companies refused to let them quit. Other reasons included fear of backlash if they resigned alone or their work environment discouraged employees from quitting independently.

Mynavi Corp. also surveyed workplaces and asked managers how often employees under their supervision had used resignation agencies. Between January and June 2024, 23.2% reported that they had employees who used resignation agencies. The most common fields were insurance, finance and IT.

Advertisement

Resignation Agencies Reflect Japan’s Mental Health Crisis

According to Momuri, most Japanese people in corporate roles have a low awareness of mental health. Social norms often discourage seeking help for mental challenges—many of which stem from their work.

This lack of support is one reason more Japanese people now turn to resignation agencies. They quit to avoid damaging their mental health and use resignation agencies to sidestep the stress of handling the process themselves.

Mr. Iida’s experience of his boss tearing up his resignation letter is not unique. In fact, it’s far from the most extreme case. Momuri confirms stories of companies forcing employees to visit temples to ‘cure’ their desire to quit. Sometimes they even receive home visits from managers pressuring them to stay.

Those fortunate enough to leave are sometimes asked to send apology letters to colleagues or deliver speeches expressing regret for their “selfishness” and “disrespect.” Of course, these are the most extreme cases–but they do occur, according to Momuri.

Some companies are notorious for resignation difficulties, excessive overtime and intense work pressure. So much so that they are labeled as “black companies.” The problem has become so severe that Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s Labor Standards Bureau has published a list of these companies to warn potential job seekers.

Generational Change Could Be Japan’s Savior

A generational shift is underway in Japan, one that may eventually ease work-related pressures and their sometimes fatal consequences. Physical strain and mental stress contribute to both karojisatsu, or ‘overwork suicide,’ and karoshi, or ‘death by overwork’.

According to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the number of Japanese people who committed suicide due to their work rose from 1,935 cases in 2021 to 2,968 in 2022. This marked a record high. While the figure has since slightly decreased, the strain on workers remains severe.

Since they first appeared in 2018, resignation agencies have become an essential ally in Japan’s work culture shift. These agencies empower young workers to prioritize their mental well-being and advocate for change, providing a way out for those trapped in restrictive work environments.

This growing reliance on resignation services underscores a generational pushback against outdated norms and signals a potential transformation in Japan’s work culture. If these shifts continue, Japan’s younger generation may indeed pave the way toward a more balanced and sustainable future for the country’s workforce. Let’s hope they succeed.

Advertisement

Dive into Japanese society:

Are Trains in Tokyo Safe for Women? A List of Women-Only Cars in Tokyo

Why Japanese People Don’t Say “I Love You”

What the Japanese Bathhouse Can Teach Us About Body Image

Navigating Cross-Cultural Divorce in Japan

Is Japan’s Cultural Aversion to Public Noise Suppressing Its Birth Rate?